Ozzy’s celebrity accounts in the renewed interest in his old band.

Ozzy’s celebrity accounts in the renewed interest in his old band.

|

| Ozzfest\r\nWith Ozzy Osbourne, Judas Priest, Slayer, Dimmu Borgir, Black Label Society, Superjoint Ritual, Slipknot, Hatebreed, Lamb of God, Atreyu, Bleeding Through, Lacuna Coil, Every Time I Die, Unearth, and others Thu, Aug 5, at Smirnoff Music Centre, 1818 1st Av, Dallas. $50.75-133.75. 214-373-8000. |

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Iron Men

Black Sabbath get boxed in time for Ozzfest.

By MATT ASHARE

The most telling, if not the most significant, part of the new eight-c.d. Black Sabbath box set, Black Box: The Complete Original Black Sabbath 1970-1978, comes at the tail end of a five-track bonus DVD hidden away at the back of the black-velvet-clad book of liner notes in a neatly camouflaged black-paper insert. After throttling their way through four of their best dark and gloomy Black Sabbath epics (“Iron Man,” “Paranoid,” etc.), shot in the cheesy psychedelic fashion so popular as the ’60s became the ’70s, the band breaks into the Carl Perkins classic “Blue Suede Shoes.” Never mind that everyone appears to be wearing black shoes to match their black outfits, or that they probably didn’t have a pair of blue shoes among them. What’s significant about this otherwise trivial moment of rock history is that it says a lot about where Sabbath’s music came from and how radically they reinvented the rock-and-roll wheel on their first few albums, all of which are included in fine digitally remastered form in the new set.

Like so many British bands of the Stones-dominated late ’60s, Sabbath came together to play the American blues, which meant everything from Robert Johnson’s devilish intonations to party anthems like “Blue Suede Shoes.” But as Sabbath’s awkward drive through the Perkins number reveals, Ozzy and his pals weren’t particularly well suited to straight-up American blues. The Stones were pretty good at it — a point that’s driven home over and over again on the beautifully packaged Singles 1963-1965 (ABKCO), a 12-c.d., 32-track set of that band’s first dozen singles.

Watching guitarist Tony Iommi, bassist Terry “Geezer” Butler, and drummer Bill Ward attempt to approximate the swing of “Blue Suede Shoes” is almost as comical as listening to John “Ozzy” Osbourne sing those lyrics. As most Sabbath fans know, Iommi had been the victim of a factory accident that damaged the tips of the fingers on his fretting hand and forced him to adopt a style that didn’t include much in the way of standard Chuck Berry licks.

So Sabbath took a run at “Blue Suede Shoes” and then swiftly moved on to creating music in their own image, drawing on their own experiences growing up on the wrong side of the tracks in working-class Birmingham, taking their name from a Boris Karloff horror film, and using Iommi’s limitations to their advantage. The result was the dark, dismal, grungy, tortured hard rock that defined anthems like “Iron Man,” “Paranoid,” and “Sabbath Bloody Sabbath.” Like many of their peers, they banged heads with social conventions of the day and took more than a few instrumental jam liberties (dated, vaguely jazzy improvs that stick out like sore thumbs on Black Box). In the process, they developed a largely inimitable, immediately recognizable sound that drew as much on their particular attributes (Ozzy’s voice, Butler’s busy bass, Iommi’s overdriven single-note Gibson SG riffs) as it did on their limitations (Ozzy’s vocal range, Iommi’s damaged digits).

Sabbath’s inability to master trad blooze may in part explain why so many critics of Sabbath’s era (1970-1978) looked down their noses at the band. After all, as far as most serious rock critics were concerned, the blues were sacrosanct. A studied rendition of Robert Johnson’s “Love in Vain” could go a long way toward keeping the arbiters of taste in your court, but Sabbath didn’t have that luxury. They were also all too willing to play along with the silly black-magic shtick that became associated with their name soon after the release of their 1970 debut, even though it had all started as little more than an inside joke. To a bunch of blokes from Birmingham, however, it would have been all but impossible to resist the empowerment that came with being feared as minions of the devil, so who can really blame them for letting the Karloff caper take on a life of its own?

It didn’t help that Butler was the band’s primary lyricist: As Rush has proved again and again, when someone other than the singer writes the words, the results are often painfully poetic if not downright dumb. (Pete Townshend is one of the exceptions that prove the rule.) Not that Zep’s infamous “If there’s a bustle in your hedgerow don’t be alarmed now / It’s just a spring clean for the May queen” has anything on a lyric like “Visions cupped within a flower / Deadly petals with strange power / Faces shine a deadly smile / Look upon you at your trial” (“Behind the Wall of Sleep,” from Black Sabbath). But whereas Zeppelin embraced flower power and did their best to change with the times, Sabbath remained rooted in the underworld of dungeon and dragons, witches and warlocks, and all kinds of other nonsense (“Faeries Wear Boots,” anyone?). The band stayed there even after Ozzy had embarked on his solo career and a number of lesser frontmen (Ronnie James Dio being my favorite) had been paraded in front of audiences to sing Butler’s lyrics. There was a point in the ’90s when Sabbath developed a certain cyberpunk fixation, but let’s not be cruel. It may have taken a while, but as time passed, it’s become possible to see past the black-magic pose and Ozzy’s clownish solo performances, to the groundbreaking music Sabbath had recorded during its first run with Ozzy. It didn’t hurt when, in the mid-’80s, American hardcore punk bands like Black Flag stopped playing fast and started churning out dark, angst-ridden anti-anthems that to a degree were Sabbath without the Satanism, punk instead of pentagrams. It would take another decade and a half for a new generation of rock-and-roll kids to come of age without having to adhere to any artificial distinctions between punk and metal. And classic Sabbath, with its gloomy sense of alienation and unison guitar/bass riffs, was perfect to be appropriated for what Seattle-ites would soon be calling “grunge.”

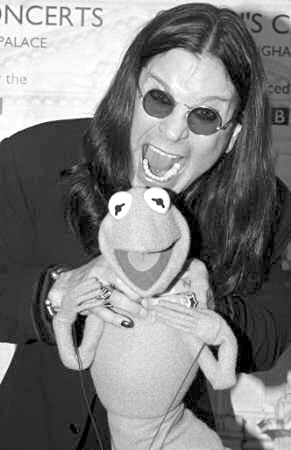

Indeed, the only real problem a reunited Black Sabbath poses for Ozzy is that when you take “Iron Man,” “Paranoid,” and the rest of the Sabbath songbook away from Osbourne the solo artist, his solo Ozzfest sets suffer mightily. Yeah, “Crazy Train,” with its video-montage homage to departed guitarist Randy Rhodes, gets the adrenaline pumping. But beyond that, it becomes painfully apparent that Ozzy did his best work with Sabbath and that his music has been on a downward spiral ever since. His career hasn’t suffered: In fact, under his wife Sharon’s guidance, Ozzy thrived while his former mates soldiered on as shadows of their former selves until he jumped back on board. And for all the considerable musical backbone that Iommi, Butler, and Ward bring to Sabbath, everyone knows that without Ozzy’s celebrity, they’d be playing the Spinal Tap circuit, puppet shows and all. l

A version of this article originally ran in Boston Phoenix.

Email this Article...

Email this Article...