|

|

|

‘we went organic to have some kind of integrity.’

|

Amy McNutt was shocked by what she saw in strawberry fields in California.

Amy McNutt was shocked by what she saw in strawberry fields in California.

|

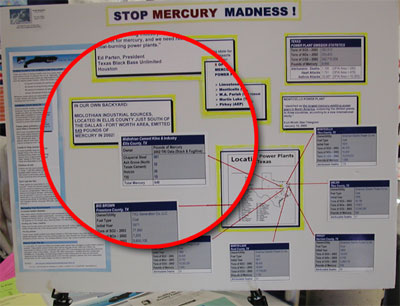

A SEED coalition display reveals high mercury contamination in many Texas lakes.

A SEED coalition display reveals high mercury contamination in many Texas lakes.

|

Paul Huston warns fellow anglers of the dangers of mercury in Texas-caught fish.

Paul Huston warns fellow anglers of the dangers of mercury in Texas-caught fish.

|

Pamela Cook is marketing director of Whole Foods Market, where you won’t find any transfats.

Pamela Cook is marketing director of Whole Foods Market, where you won’t find any transfats.

|

Robert Hutchins, shown here with three of his children, is a far-from-typical Texas rancher.

Robert Hutchins, shown here with three of his children, is a far-from-typical Texas rancher.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Perils on Your Plate

Threats to our food supply are pervasive —

but don’t stop eating yet.

By WENDY LYONS SUNSHINE

I stare at my plate. Grilled fish is the main attraction — no fatty sauces, cholesterol-laden ribs, or potentially mad-cow-carrying beef for me. I’ve skipped the smothered fries and gone with steamed broccoli. Fresh green salad is sprinkled with toasted croutons and drizzled with vinaigrette. The glass glistens full of water and lemon, not sugary soda.

The restaurant’s white tablecloths and wood paneling are squeaky clean — heck, all the patrons are wearing shoes and there’s nary a mustard smear on the servers’ tunics. Even the dessert cart is nowhere in sight. What — other than the eventual check at the end of the meal — could possibly be unhealthy here?

Unfortunately, as I learned in the course of researching this story, the answer is: plenty. Despite USDA grading, FDA guidance, state environmental rules, city health inspectors, and consumer groups, the truth is that eating — whether at a restaurant or in the comfort of your own home — is a surprisingly risky business these days.

Start with the fish. Let’s hope it didn’t come from Texas waters — or from ocean waters, either, unless you have an appetite for brain-damaging methyl mercury. Was the broccoli field fertilized with hazardous mining wastes? I have no way of knowing. The fresh green leaf lettuce? Probably has rocket fuel running through its leafy veins. Croutons? To make them crunchy and last longer, they’re baked with heart-choking transfats. The water in my glass? Fortunately, it doesn’t come from the Midwest, where weedkillers have contaminated the water supply of more than seven million people. Or from California, where a banned pesticide contaminates the tap water of another million people. But my drink might just contain common, cell-damaging byproducts of chlorination, including a powerful cancer-causing chemical known as Mutagen X. No kidding.

Unless your diet is totally and utterly organic — so you know what you’re eating, where it was grown, how it was raised, what it was nourished on, watered with, fattened with, and cooked in — it’s increasingly hard to keep toxins off your plate and out of your body. Even then, some chemical residues have become so ubiquitous that there’s no avoiding them. In the 21st century, it seems, the last century’s “better living through chemistry” mantra is coming back to bite us.

At her Magnolia Avenue restaurant, young filmmaker-turned-restaurateur Amy McNutt is endlessly busy — overseeing meals, handling paperwork, bussing tables. But she sat down in her Spiral Diner long enough to explain what triggered her interest in how food is grown, and why she buys organic whenever possible.

A vegetarian at age 19, she was living in central California, close to crop land. What she saw there shocked her. “These guys were out in the field wearing spaceship suits while they were spraying pesticides,” said McNutt. “It was so toxic that they couldn’t even be in a field of strawberries without a self-contained suit and a breathing apparatus.”

The haz-mat vision so unnerved McNutt that she immediately changed her buying habits. “I was more concerned about people out there working in it every day than in my own health” admitted the native Texan. “Migrant workers don’t even get those suits.” She began shopping at a local organic food market for produce that had been intentionally raised without the help of pesticides, herbicides, or synthetic fertilizers.

Research confirms that McNutt was right to be concerned. The dangers of pesticides to farmworkers have been documented for years. But more and more research shows that even the amounts that reach the average consumer can be dangerous. Researchers in Washington state, for instance, found recently that pre-schoolers who ate ordinary supermarket foods had pesticide levels six times higher than youngsters whose diet was restricted to organic products. And four out of five common pesticides — used on the vast majority of non-organic produce sold in American grocery stores — have the potential to cause cancer or other health problems.

A doctor at Stanford University School of Medicine discovered that people who were exposed to common pesticides — the kinds of insecticides, herbicides, weed killers, and fungicides used both by farmers and many homeowners — were twice as likely to suffer from Parkinson’s later in life. And in 2003, a British medical journal study found a striking correlation between pesticide residues and the occurrence of breast cancer. Women who were battling cancer had five to nine times more detectible pesticides in their bloodstreams than those who were cancer-free.

In another recent study, Michigan researchers found that girls between 7 and 11 years old who had been exposed to DDE (dichlorodiphenyl dichloroethene, a metabolite of the pesticide DDT) grew more slowly than did those without the exposure. What makes this scary is that DDT was banned from use in the 1970s. Pesticide residues are so persistent that they can remain in the soil for decades. In fact, the researchers remarked that because of DDT’s once-widespread use, it was difficult to find children for the study who had not been exposed.

The health risks of pesticides are especially significant for growing children. In a report called “Trouble on the Farm,” The Natural Resources Defense Council pointed out that farm kids are exposed to highly toxic agricultural pesticides just about everywhere — in the air, in their water, on their food, in dust tracked in from the field on shoes — but that kids who are simply eating contaminated food are also vulnerable. Children’s low body weight makes their exposure proportionally greater, and their developing bodies are much more vulnerable to disruption by outside toxins.

Traditional farmers and gardeners know that keeping the bugs and weeds away is only part of the equation for getting good yield from the soil. The other major factor is fertilizer. It must have seemed like the height of recycling (also known in business circles as making money off something that used to cost money), therefore, when some farmers started spreading sewage sludge on crop fields and pastures as a fertilizer. Hey — the sludge is rich in nutrients and water, and putting it back on the land means it doesn’t have to be otherwise cleaned up. An innovative North Carolina farm, for example, uses high-strength wastewater from its 4,000 pigs to grow greenhouse tomatoes.

Soil can neutralize a certain amount of toxins. But sludge is sometimes chock full of heavy metals (like mercury, lead, or cadmium); industrial chemicals (like polychlorinated biphenyls, known as PCBs); or harmful bacteria. When heavily contaminated sludge is applied to land, local plants and animals, not to mention the groundwater beneath — can absorb the bad stuff. Crops can be affected — but cows, higher up on the food chain, are even more likely to accumulate toxins from their grazing.

Farmers are always expected to be mindful when applying sludge or conventional fertilizers. Even when they are, however, they may not know just how unhealthy the stuff they’re spreading is.

A few years ago, a Seattle Times reporter described how farmers unwittingly spread toxins on their fields because of poor fertilizer labeling. In his book, Fateful Harvest: The True Story of a Small Town, a Global Industry, and a Toxic Secret, Duff Wilson exposed the lack of oversight on fertilizer manufacturing. Instead of paying for proper disposal of hazardous mining wastes, mining companies had discovered that it was cheaper to repackage the waste and sell it as fertilizer. The product label doesn’t mention when hazards like lead, mercury, dioxins, cadmium, and arsenic are included at no additional cost. Since Wilson’s reports came out, Washington state has implemented strict disclosure rules for fertilizers. Texas is one of a handful of other states beginning to limit toxins in fertilizer.

But calls to local stores indicated that at least one such toxin-laced product is still on shelves here.

Texas isn’t doing well at all in regulating another poison that can have serious effects on food contamination. Mercury starts out in places like power plants, gets spewed out into the air, lands in and contaminates the water, and then gets served up — to the unwary — in fish. Right now, Texas leads the nation in the amount of airborne mercury being blown out into our skies.

“When we look at the mercury emissions in the air pollution category, we’ve seen a rise for the past three years,” said Karen Hadden, clean air coordinator for the SEED Coalition in Austin, a Texas-based group supporting clean air and clean energy. The latest government data show that more than 9,800 pounds of mercury blew into Texas air in 2002.

A pervasive industrial material, mercury is used in a host of products from fluorescent light bulbs to batteries to dental fillings. The danger begins when mercury flies uncontrolled into the air as a by-product of waste incineration, cement manufacturing, and coal-fired power generation. The stray mercury settles on land and water, where it gets absorbed by tiny bacteria and converted into a more toxic form, methyl mercury. These mercury-laden bacteria are eaten by tiny fish, which in turn get eaten by larger fish.

Methyl mercury is stable and doesn’t disappear magically. It remains stored in the cells of fish that consume it. As they feed and grow, the larger fish — those higher up in the food chain — become the most heavily contaminated.

Initially, effects may not be noticeable, but as they become more contaminated, fish display nervous system and reproductive damage. Even a minute quantity of exposure will affect a fish’s coordination and make it easier prey, said Dr. David Marrack, a retired Houston physician and former environmental researcher. And that’s bad news for the animals at the top of the food chain: us.

Mercury’s neurotoxic effects take place at the cellular level, Marrack explained. We may not recognize they’re occurring until so many nerve cells are damaged that behavior and learning ability are obviously affected. The effects of mercury poisoning are wide-ranging, from memory loss to numb fingers to reduced fertility.

“Every atom of mercury is potentially poisonous. Period,” Marrack said. Methyl mercury is especially damaging to human fetuses and infants, whose nervous systems are still forming. That’s why fish consumption advisories issued by the government are strictest for pregnant women.

Because of mercury contamination, the Texas Department of Health warns adults to eat no more than one pound per month of fish caught from B.A. Steinhagen Reservoir, Sam Rayburn Reservoir, Big Cypress Creek, Toledo Bend Reservoir, or Caddo Lake. Health officials recommend that children consume half that amount.

In 1993, 27 states had mercury advisories for their waters. Within 10 years, that number had shot up to 44. According to a report by the U.S. Public Interest Research Group called “Fishing for Trouble,” recreational fishing across the country is in jeopardy from mercury pollution.

Changing your order from Texas-caught catfish to saltwater seafood may not help, however. In 2003, a whopping 92 percent of the Atlantic coast and 100 percent of the Gulf coast were under seafood consumption advisories, according to EPA estimates. Hawaii’s entire coast was under a similar warning. The advisory means that scientists recommend people limit the amount of seafood they eat from those areas.

Mercury pollution means that delicacies at the top of the food chain, like swordfish and tuna, are the most toxic to humans. People have gotten mercury poisoning just by eating a tuna fish sandwich for lunch every day. There’s nowhere to hide from the problem, either. In the Arctic, remote Inuit fishermen who dine heavily on seals and whales have been found to have — by far — the highest bodily concentrations of mercury ever recorded.

Hadden wants Texas to get rid of its worst-in-the-country rating on mercury emissions. She points out that modern smokestack technology, available now, could capture 90 percent of Texas’ coal plant mercury before it spews into the atmosphere. SEED is part of an alliance of 25 organizations seeking a mandate from the Texas Legislature for a 90 percent reduction of industrial mercury emissions during the current session.

Environmental groups, however, are just one section of the alliance: The Texas Medical Association is pushing for immediate adoption of tighter standards. And fishermen themselves are working to get mercury out of Texas waters.

In Mesquite earlier this month, local groups fighting mercury pollution manned a booth at the Fishing & Outdoor show. Paul Huston, aquatic resources chairman for the Dallas Sierra Club, and his wife Patsy, both avid anglers, spent hours at the show — soliciting signatures on EPA petitions and warning their fellow fisher-folk that eating Texas fish is dangerous for their health.

One aisle over at the Big Town Expo Center, Sparky Anderson, executive director of SMART (Sensible Management of Aquatic Resources Team), explained that sportsmen are ready to get political about pollution. The groups he represents, while traditionally loath to hold hands with professed environmentalists, have joined the alliance working to solve the state’s mercury problem.

“Anglers are some of the best field scientists there are. They’re out on the lake every day, and they see differences that a state-funded scientist observes only four times a year,” said Anderson, who’s also a lobbyist for the Texas Black Bass Fund. He wants to put fishermen’s savvy to use in writing better laws.

Ed Parten, president of Texas Black Bass Unlimited, agreed. “Any time you have poor water quality, it’s a proven fact, you’re going to have poor fishing,” he said. “Something needs to be done about it.” Parten is a committed angler who fishes for both pleasure and sport. He competes in two dozen fishing tournaments a year and is adamant that Texas fishing has gotten worse over recent years. Parten pulls plenty of fish out of the water in Texas — but he won’t eat them because of mercury contamination.

Wearing jeans and the Whole Foods’ signature green apron, Pamela Cook explains that her market shouldn’t be called a health food store.

“We never say we are a health food store,” says Cook, marketing director at the Arlington location. “That’s a public perception.” Still, their commitment to natural foods is strong. The Austin-based chain carries organic produce and organically raised meats. And she’s particularly proud that her store no longer carries any product containing transfats (also known as partially hydrogenated vegetable oils, trans-fatty acids, and shortenings).

Calorie-conscious folks who transferred their allegiance from butter to margarine years ago have found out more recently that they may have jumped from the frying pan into the fire, healthwise, because of transfats, man-made inventions that have become ubiquitous in processed foods. The problem is, study after study demonstrates that transfats are more dangerous to human health than saturated fats like butter and lard.

Not only do they increase bad cholesterol in the bloodstream, but transfats suppress the good cholesterol. Harvard researchers found a direct link between consuming these fats and an increased risk of heart attacks and concluded that “... consumers should be aware of the harmful effects” of transfat products.

Transfats have even been linked with increased colon cancer in certain segments of the older population. A University of Utah study concurred: “It seems prudent to avoid consuming partially hydrogenated fats... .”

Start reading ingredient labels, and you’ll see transfats just about everywhere. It’s nearly impossible to find conventional bakery goods, ordinary frozen foods, or even children’s snacks without them. That’s because they extend shelf life. Once I started scanning labels in my neighborhood supermarkets, I was shocked to find partially hydrogenated oils on virtually every aisle. Even many products branded as a “Healthy Choice” use them. Most disappointing of all: The whole-grain bread at my favorite French restaurant includes them. Quelle horreur.

Forty miles northeast of Dallas, near Greenville, the road to Rehoboth Ranch turns from asphalt to a rutted gravel lane. The approach, sheltered by tight rows of thin pine trees, feels like driving into a bumpy time machine.

A cluster of sturdy low buildings rolls into sight. When his visitor’s car comes to a stop, ranch owner Robert Hutchins steps forward, extending his thick hand in welcome. Although Hutchins is dressed in typical ranching gear — denim overalls and jacket, baseball cap, and heavy workboots — Rehoboth is not a typical ranch.

For one, the scale here is smaller. On these 100 acres, there are no immense storage bins of grain, no mountains of manure, no thousands of a single species being readied for feedlots or crammed indoors for easier processing. Hutchins and his wife, Nancy, are doing something revolutionary in the heart of Texas. They’re raising commercial poultry and livestock the way they believe the Creator originally intended: grazing them in small herds and flocks, exclusively on grass.

Hutchins and his visitor step across a muddy yard to survey fields that are bright green despite the chilly season. Juvenile goats poke their flop-eared heads through the fencing. Next year they will give milk for the family and its customers. Hutchins explains he’s one of just a handful of farms in the state licensed to sell raw unpasteurized goat’s milk.

Not far from the modest house where Hutchins and his wife live with 11 of their 12 children, dozens of chickens and roosters mill about in a moveable pen, clucking in the bright sunlight, their feathers and red combs vivid against the grass. A few are roosting inside a contraption with sliding metal walls. Hutchins explains that it’s a henhouse on wheels, ready to follow the flock to the next grassy spot. Farther from the house are turkeys, and near a group of trees, sheep and the occasional cow graze.

Hutchins also sounds a little different from conventional ranchers. When he describes Rehoboth’s mission, the phrase “optimally nutritious” pops up time and again. Sure, Hutchins follows typical organic guidelines. No synthetic growth hormones are used to speed young livestock to the slaughterhouse. (Growth hormone residues are believed to cause children to reach sexual maturity faster, among other problems.) No antibiotics are pumped into the animals, either — though they’re typically needed to keep farm livestock from getting sick in overcrowded conditions. Preventing chemical contamination is just the beginning of healthy foodstuffs, Hutchins believes. The rancher is convinced that a natural, low-stress lifestyle for the animals is also critical to success.

“Our animals spend their entire lives in their natural environment eating their natural diet,” says Hutchins, a Navy veteran and former Raytheon executive. “That’s what differentiates grass-fed meat from what is commercially available and mass produced — even mass-produced organic meat that you can find at Whole Foods or Central Market.”

Rehoboth Ranch’s meat is not certified organic, in part because Hutchins doesn’t want to spend the $1,000-plus annually that certification requires. The ranch’s annual gross is under $200,000. The family now survives on one-fifth of the six-figure income Hutchins once pulled in working in the defense industry.

The rancher feels that the certified label is more important for organic wholesalers seeking supermarket outlets and that it’s less important when you have a direct relationship with retail customers who know your operation. Rehoboth sells only from a tiny store on ranch premises and from the Texas Meats Supernatural stand in Shed 2 at the Dallas Farmer’s Market.

Even without the organic label, consumers have responded favorably. They purchase every last bit of chicken, pork, lamb, beef, turkey, and egg that comes off Rehoboth Ranch. There’s a waiting list for the fresh goat’s milk, and during this visit, chicken and lamb were entirely sold out.

USDA-certified organic livestock are required to be kept free of antibiotics and synthetic hormones, and their feed must be uncontaminated. But Hutchins ups the ante on the government. He argues that mass-produced organic meats are still factory farmed and finished in a feed lot. This unnatural diet stresses the cattle, which changes the texture of the meat and leaves it less nutritious.

“It’s true that organic standards prohibit the use of hormone implants and sub-therapeutic levels of antibiotics, but the meat is not optimally nutritious,” he says. “When you take a beef steer, for example, and put him in a feedlot for 120 to 150 days, within 100 days over 80 percent of the omega-3 essential fatty acid is gone from the meat, and it cannot be replaced.”

Cattle have multiple stomachs designed to slowly ferment their grass diets. Feeding them large quantities of grain short-circuits their elaborate digestive systems, says Hutchins, and as a result, feed lot cattle suffer indigestion so much that they are given antacids along with the grain.

Beef experts say that, indeed, the use of antacids in cattle is widespread, although it has been reduced in recent years, as feedlot operators have become more sophisticated. The practice does affect the chemistry of the meat, but beef authorities say the practice is not unhealthy for humans. Still — who knew you had to be worried about antacids before the steak arrived?

Hutchins points to research showing that meat from grass-fed, pastured animals is not only free of synthetic hormones, antibiotics, and mad cow disease, but also has considerable nutritional benefits, including higher levels of healthful omega-3 fatty acids, beta-carotene, and vitamin E than do conventionally raised meats.

Jason Sawyer, assistant professor of beef cattle production at Texas A&M University, acknowledged that an animal’s diet does affect meat’s chemistry. But Dr. Sawyer thinks the differences between conventionally raised and grass-fed beef are insignificant.

“Beef is never going to provide a high proportion of those [beneficial chemicals] in a diet,” he said. “If you start out with half of a percent and increase it to 1 percent, it’s a 100 percent improvement, but it’s still only 1 percent” of the recommended amount.

The USDA instituted its organic certification program in response to an increasingly vocal public concerned about the safety of the country’s food supply. Health-conscious consumers and food producers around the country are keeping a watchful eye out, trying to prevent the certification process from being diluted and, in their eyes, made meaningless.

Who wants to dilute it? Big agribusiness, which sees terrific opportunity in the organics marketplace, and wants to lower the bar for entry. The USDA reported that in 2000 — two years before government certification was even available — consumers spent over $7.8 billion on organic food. And sales of organics continue to grow at a rate of about 20 percent annually, according to a recent survey by Whole Foods.

Even now, some food producers feel that the government’s 100-plus-page organic certification guidelines don’t go far enough. Two vocal critics of the USDA program are Kristie and Rick Knoll, considered pioneers in the organic food movement. On their modest 10-acre farm an hour east of San Francisco, they grow 100 different products. “We went organic to have some kind of integrity, and every time we turn around, the guys in the government are trying to knock the legs out from under it,” Kristie Knoll said. She and her partner don’t bother with USDA organic certification, because they feel it is too lax. For example, it allows lettuce to be rinsed with chlorinated water.

Chlorinated water? Yep. That may be a problem, too.

So. You read labels, you buy organic, you start noticing whether the salmon at the store is farm-raised or wild. And you swear that lips that touch transfats will never touch yours. Feeling good about yourself, you buy some nice organic broccoli, get out your shiniest saucepan, add a little water at the sink, and get ready for a nice healthy meal.

Aaaagh. Step away from the stove. Toss out the water. And the pot with it.

In the last couple of years, the FDA has become concerned that perchlorate (the primary ingredient of rocket fuel, also used in explosives, rubber manufacturing, and other industrial processes) may be contaminating our food supply through irrigation water and bottled waters. Initial field tests on a range of products from around the country were released in late 2004. Results varied wildly.

The green leaf lettuce sampled by researchers was found to have anywhere from 1 to 27 ppb of perchlorate contamination. Bottled water came up virtually clean, while whole milk averaged 6 ppb. But how much proto-rocket fuel can a person ingest before it gets to be a problem? With only preliminary data in hand, scientists, industry lobbyists, consumer health experts, and the government are still squabbling over that.

As for Mutagen X, the powerful mutation-causing agent found in the drinking water of several Massachusetts public water systems a few years ago — it’s one of several by-products of chlorination. The jury is still out on their effects, which may vary based on local water treatment facilities. Some studies show a dramatic increase in bladder cancer from exposure to chlorinated water, while others say the effects are negligible.

And what about that saucepan? Aluminum is one of the heavy metals (like mercury and lead) considered to be neurotoxic. Accumulations of aluminum are found in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients, and it has been linked with other damaging health effects as well.

We can control our own kitchen cabinets. But most of us don’t get to check out what’s sitting on a restaurant’s stove or how our processed foods were prepared. If the chefs are using uncoated aluminum cookware to simmer up acidic foods like tomatoes (think chili or spaghetti sauce), then we may well be getting a toxic mouthful. For example, no aluminum migrated into a potful of porridge cooked up by Finnish researchers. Yet when they boiled rhubarb in the same aluminum pot, an astonishing 170 mg/kg of aluminum was drawn into the fruit.

Americans may not be doing much on the rhubarb or porridge fronts — but some of us are now afraid of our cookware nonetheless. And filtered water is looking less frou-frou all the time.

In his book, Why Things Bite Back, Edward Tenner explores how innovations often carry unintended effects. For example, the pesticide DDT appeared amazingly safe when it was first introduced in the 1940s. Unlike earlier pesticides, it did not seem to harm people who came into direct contact with it.

Yet today, decades after being banned, DDT is linked to cancer and stunted childhood growth. “DDT came to menace us in the future because it seemed so safe in the present,” wrote Tenner. The lesson: It’s hard to predict consequences. The Next Big Thing for industry could in fact have a trickle-down effect that further compromises our food supply. Each time, it seems, that a major development “improves” our lives, some unintended consequence becomes a drawback. For example, the canning process improved food safety radically, but the lead solder in cans caused health problems, until the threat was recognized and the process was changed.

In our culture, useful chemicals and new technology are presumed innocent until they’re proven to be contaminating our food, water, or air. Even when damning evidence builds up, those responsible often stick their heads in the sand for as long as possible. Case in point: coal-burning power plants spewing mercury.

In the case of the seemingly endless threats to the safety of America’s food and water supply, it often seems that no one is looking at the big picture, trying to answer the ultimate questions about how much food supplies can be contaminated, before humankind and the environment are significantly damaged. In the meantime, consumers grow weary of the whirl of reports, and either close their ears or end up scared to eat anything more complicated than a home-grown carrot.

Many researchers believe that the immediate “big picture” is this: Most of these problems are manageable — as long as folks eat everything in moderation and try for a heart-healthy, low-fat diet.

Dr. Gina Solomon, a physician and senior scientist with the Natural Resources Defense Council, said that eating a heart-healthy, low-fat diet will also expose people to fewer environmental contaminants. That’s because chemicals like PCBs, dioxins, and flame retardants accumulate in fat — and in our bodies — over time. “So fatty foods like meat, cheese, and ice cream, and fatty fish like farm-raised salmon contain the highest levels of those contaminants,” she said. Besides warning breast-feeding moms away from such foods, she said, the National Academy of Sciences last year also began warning that girls should start avoiding fatty foods in childhood, to lower the risks, years later, to their own children.

For regular fish eaters, Solomon recommends using the mercury calculator on the NRDC web site (www.nrdc.org), to find out just how much of that contaminant they are probably gettting, based on their diet.

What about grass-fed meats, such as those raised by Hutchins — are they any better? “Organic, grass-fed meat is likely to be healthier,” Solomon acknowledged.

It is also true, however, that, even eating organically and healthily, it’s impossible to avoid some of the results of humankind’s former carelessness. “Since PCBs contaminate our entire environment, it’s sad but true that even organic food is not able to completely escape these chemicals,” she said. Although the food supply is gradually becoming less contaminated with these chemicals, “almost any sample of meat, fish, ice cream, cheese, or butter” is likely to harbor some trace of these persistent toxins.

The Environmental Working Group, a nonprofit that carries out environmental investigations, has issued a shopper’s guide to fruits and vegetables, available on its web site (www.ewg.org). Based on USDA test data, the group recommends you avoid conventionally grown apples, bell peppers, celery, cherries, grapes, nectarines, peaches, pears, potatoes, raspberries, spinach, and strawberries, because they carry the most pesticide residues. Non-organic produce that’s likely to be less contaminated: asparagus, avocados, bananas, broccoli, cauliflower, corn, kiwi, mangoes, onions, papaya, pineapples, and sweet peas. And, the organization recommends, toss those old aluminum pots and replace them with stainless steel.

Jill Wachter admits she carries more pounds than she should and doesn’t exercise enough. Yet, while their retirement-age friends all battle heart disease, cancer, and diabetes, both she and her husband remain free of ailments.

The Fort Worth couple are frequent patrons of Spiral Diner and have been vegetarians for 25 years. Fifteen years ago they both switched to eating organics. Why? “Not wanting to put poisons in my body,” said Jill, who will turn 60 this year. She is convinced that “clean foods” offer huge benefits, beyond their superior flavor.

Neither she nor her husband takes any medication, and both enjoy good blood pressure, healthy cholesterol levels, and plenty of energy. And it’s not because they come from genetically superior stock.

“My mom died of cancer. My dad had heart surgery when he was 50 and died of heart disease. Fred’s dad died of heart disease,” explained Jill. “Fred’s one of six children. Four are diabetic and on heart medication; they’re at the doctor all the time and having surgery. They’re not well.” What about Fred’s other sister, the one who doesn’t have all those health problems? She has a garden where she raises her own organic food, including her own chickens, whose eggs she eats. The only meats her diet includes are fish and chicken, each once a week.

Fred Wachter, 63, believes that he and his wife have also lightened their toxic load by avoiding tap water. “We’ve been drinking steam-distilled water,” he said. “I think that is much healthier. They take all the additives like chlorines and fluorides out. Some researchers think certain forms of cancer, like bladder cancer, can be traced to chlorine in the water.”

“One of our friends used to tease us,” said Jill. “He would say things like, ‘I just mowed the grass, do you want to come over and have some?’ Now he’s having severe health problems, and all of a sudden is real interested in this diet.”

“Unfortunately, what we see in our customer base is that they are afflicted by something,” said Cook, of Whole Foods. “They have what I call ‘life-altering events.’ They may find out they have diabetes or heart disease,” she said. “That’s the jolt that they need to make them aware of what they put into their body.”

Email this Article...

Email this Article...