Former ‘Star-Telegram’ reporter and UTA journalism prof Phil Vinson brings his acute eye to ‘the easy years.’

Former ‘Star-Telegram’ reporter and UTA journalism prof Phil Vinson brings his acute eye to ‘the easy years.’

|

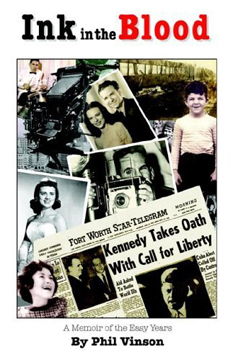

| ‘Ink in the Blood: A Memoir of the Easy Years’\r\nBy Phil Vinson\r\nVirtualbookworm.com Publishing\r\n$14.95 296 pps. |

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Stains

A local veteran journo is more concerned with matters of the flesh than those of the pen in his recently published memoir.

By BETTY BRINK

Given the terrible times we live in, journalist Phil Vinson’s coming-of-age memoir set in 1950s West Texas and Fort Worth may seem as quaint to twentysomethings as reruns of Father Knows Best. As award-winning author Mike Nichols writes in the foreword to Ink in the Blood, it was a time when “AIDS meant ‘helps,’ when junior high schools did not have metal detectors [and] senior high schools did not provide day-care centers for the babies of students still babies themselves.”

African-Americans still lived in the “Other America.” “Dysfunctional” had not entered the lexicon of words used to describe families — there were either “good” or “bad” families, and everyone in town or the neighborhood knew the difference. Assassinations of popular leaders happened only in countries ruled by despots. And Vietnam? Few folks could find it on a map.

Despite its title, Ink, Vinson’s first book, is not the story of his years as a journalist at the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and elsewhere, where he covered events like the 1963 assassination of John Kennedy. This often hilarious, often sad chronicle of his growing-up years stops where his career starts.

Born in the Panhandle town of Childress in 1940 to Florence Copelin and Doyle Vinson, Phil was an only child until the age of 19, when his parents had their second son. He grew up in the news business — his father, a pioneering Texas journalist, and two of his father’s siblings worked in newsrooms all their lives.

Vinson’s account of his late parents’ romantic-movie-plot meeting in Childress is one of the book’s best-written chapters and one that makes you want to know more of the couple. In 1936, a 26-year-old reporter from a “good family” was sent to cover a wreck caused by a sudden ice storm. The driver was killed. His passenger, a woman, survived and made her way down the road through the sleet to a nearby café. She was sitting bloody and shivering over a cup of coffee when the reporter found her. A pretty girl from “the wrong side of the tracks,” she let him take her to the hospital, where she was treated and released. “Come by the paper sometime,” the reporter told her as he drove her home. “We’ll go get an ice cream cone.” They married two years later.

The family later moved to Fort Worth, and Doyle Vinson went to work for WBAP radio and later its tv outlet, where he produced the popular and long-running Texas News program. He was the first tv newsman in the Southwest to set up a live remote broadcast, covering Harry Truman’s speech at the T&P Depot during Truman’s whistle-stop presidential campaign in 1948. The Vinson family “loved to argue,” Vinson writes, but had “an ingrained sense of getting things right.” The author likely sharpened his storytelling skills by listening to arguments about everything from politics to local gossip around his grandmother’s kitchen table.

By tagging along with his newsman/photographer father, Vinson also witnessed some of Fort Worth’s most momentous events, including the 1949 flood that rose to the second story of Montgomery Ward’s on West Seventh Street and the removal of the body of notorious local gangster Tincy Eggleston from a well in an area north of Fort Worth. “What is that smell, daddy?” Vinson recalls asking. His father’s answer: “That’s rotting flesh.”

Those dramas aside, the content of Ink, according to Vinson, is “the easy years,” when he was growing up in West Texas and in Fort Worth right after World War II. People didn’t lock their doors, kids roamed outside ’til supper time and played sandlot baseball without the intervention of any adults, and teen boys — like their fathers beforehand and sons later — obsessed over sex. Puberty, Vinson writes, was a time when his life seemed to be “one continuous erection.” His account of the angst of his shy and insecure high-school self, adoring of the homecoming queen from afar but too fearful of rejection to ask her for a date, rings true no matter what generation you belong to.

Vinson’s most pressing needs in 1950s Cowtown were getting laid before he graduated from high school and finding liquor stores that would sell booze to him and his high-school buddies Lou Hudson, who also became a Star-T journalist, and Lanny Priddy, now a Fort Worth lawyer and author of legal mystery novels. While the boys found their liquor stores, Vinson at least had to wait until 1960 to fulfill that other need — at a two-dollar brothel on Jacksboro Highway, now long defunct, where a prostitute named Ruby told him to “git them britches off, and let’s go.”

Between the chapters on the high school sex that consistently eluded him, Vinson takes the reader on a sentimental trek through haunts that Fort Worth hasn’t seen in decades: Skillern’s Drug stores and their famous soda fountains, the Hotel Texas’ Crystal Ballroom with its huge rotating globe of twinkling lights, the Clover Drive-In, the Gateway Theatre on East Lancaster, the Capri Art House on the West Side, the original Cats baseball team, the old LaGrave Field, and the lovely art-deco Medical Arts building where his father worked for years in WBAP’s 17th-floor studio. The author freely drops the names of family, friends, and teachers who gave succor to his sometimes lonely and scary journey into adulthood.

At the middle of the 20th century, Vinson’s generation of white kids was probably as innocent as any had ever been in America — or would ever be again.

When the budding reporter and news photographer graduated from Polytechnic High School in 1958, the myriad social ills festering just under America’s surface were about to erupt. As a cub reporter for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram, Vinson would soon be covering those eruptions, including the 1963 Kennedy assassination. He became a footnote in that historic story through the Star-T piece he wrote in which he recalled a second-grade classmate at Lily B. Clayton Elementary School, a “curly-haired boy with a big smile”: Lee Harvey Oswald. “There was little to write, except that boys looked up to him,” Vinson writes in Ink, “probably because he was a year older and ... bigger.” When Vinson interviewed their retired teacher, her only memories of Oswald were that he looked “like someone from the Bowery Boys” and told the kids he was strong because “I eats me spinach.” Still, Vinson’s story made the wires, and he would be called by the Warren Commission to testify about his brief encounter with the spinach-eating assassin when they were 7 and 8 years old.

Ink is a good read, filled with the history of an era in Fort Worth, brought lovingly and vividly to life through the eyes of a young boy and young man who was a keen observer of the quirks, peculiarities, tragedies, and triumphs of his fellow time travelers.

Email this Article...

Email this Article...