Parker: ‘This project is first and foremost about restoring levees.’

Parker: ‘This project is first and foremost about restoring levees.’

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

A Mighty Stream of Money

Lobbyists are having a field day at the Tarrant Regional Water District.

By DAN MCGRAW

The Tarrant Regional Water District has long portrayed its Trinity River Vision plan as a done deal. The $435 million flood control/economic development project has moved through the political landscape — both locally and nationally — quickly and without much opposition. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has approved the plan, designating $110 million to create a lake and a bypass channel under the auspices of flood control.

The water district also has plenty of help in legislative circles. U.S. Rep. Kay Granger of Fort Worth, a member of the key House Appropriations Committee and a driving force behind the Trinity project, was able to quickly push through Corps funding for it, via what’s called an “earmark” bill. U.S. Sen. Kay Bailey Hutchison of Texas, who sits on the Senate Appropriations Committee, has actively lent her support. And when the water district needed legal room to expand its use of eminent domain to take property for economic development, State Rep. Charlie Geren of Fort Worth got a bill passed in the Texas Legislature two years ago specifically written for the Tarrant agency. It might seem that such a project — with many big hurdles already overcome and key lawmakers backing it — would not need the help of outside lobbying firms to further grease the political wheels. But the reality is that the Tarrant water district is spending more on lobbying than almost any local government entity — more than the Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport or Dallas Area Rapid Transit, more than the cities of Fort Worth and Dallas combined.

According to records obtained by Fort Worth Weekly under the state open records law, the district will spend about $600,000 this year on outside lobbying firms. DFW Airport, by comparison, will spend $560,000 with two Washington lobbying firms, and DART has budgeted about $310,000. Fort Worth paid its Washington lobby firm $168,000 in 2006, and Dallas spent about $240,000.

The differences in lobby spending become even more pronounced when the relative size of the budget for the water district is compared to the other governmental agencies. Fort Worth, Dallas, DART, and the airport all have annual budgets of more than $1 billion — and the cities have long lists of federal concerns and programs that the lobbyists watch out for. The Tarrant water district, on the other hand, had operating expenditures of just $15.6 million from its general fund in 2006.

The Tarrant agency’s heavy hand with lobby money is also unusual among the ranks of Texas water districts. The North Texas Municipal Water District, with a budget and Dallas-area service territory similar to the Tarrant district, has no lobbyists in Washington or locally. According to federal records, El Paso Water Utilities spent $51,000 on Washington lobbying last year, while the San Antonio Water System spent less than $10,000.

Trying to find out why the water district needs to spend so much on lobbying is difficult. Neither Trinity River Vision Authority director J.D. Granger — son of the congresswoman — nor water district board president Victor W. Henderson returned calls seeking comment. Board vice president Hal S. Sparks III said it was not “his place” to comment on such contracts and referred all queries to Tarrant water district general manager Jim Oliver.

Newly elected water district board member Jim Lane said he was unaware of some of the contracts, since they had been awarded before he joined the board last year. “But you always have to realize that with the federal component to what we are doing with Trinity River Vision, you have to spent money on qualified lobbying firms who help keep the project moving,” he said.

But others are scratching their heads over the sheer amount being spent.

Steve Ellis, vice president of Taxpayers for Common Sense, a Washington-based government watchdog group, said that a lobbying budget of well over half a million dollars a year for a project like Trinity River Vision “is a huge amount of money, even for Washington.” And with Granger and Hutchison both working for the project on the appropriations panels, and the Corps of Engineers already on board, there seems little value to be gained from such spending, he said.

“One of two things is going here,” Ellis said. “Either they need a lot of lipstick to put on this pig, or this is an opportunity for a lot of people to get financially well off. But this much is real: A water district in Texas doesn’t need to be spending this much public money, especially in Washington.”

Bob Lukeman, a local opponent of the river project, echoed that question about who’s really benefiting from the lobbying money. The water district’s spending “is like an iceberg, because we only see the top, and they are hiding the huge amount that has either been spent or is coming down the line,” said Lukeman, who owns a photography studio and whose property will likely be taken through eminent domain. “When I hear they are spending this much on lobbying, it bears out just how important it is for them to succeed, and there must be a huge payoff, a pot of gold at the end if they do.”

Clyde Picht, who lost to Lane in the water district board race last year, said, “This is a local agency that should basically be concentrating on delivering water cheaply and efficiently to the cities in North Texas. Why would they even need any lobbyists in Washington?”

He has recently announced he will seek a new term on Fort Worth City Council — in part to continue his opposition to the Trinity Vision project. “Their spending habits are getting out of hand,” he said. Picht noted that the water district is already spending more than $100,000 a year on J.D. Granger’s salary, “and I figured maybe part of his deal might be that he has to call his mother every once in awhile. But I guess they have to hire someone in Washington to keep in contact with her.”

Since October 2001, the district has paid Washington lobbying firm Hicks-Richardson $256,653. The company is budgeted for $60,000 this year. Another Washington lobbying firm, Welch Resources, is due to receive $120,000 in fiscal 2007, and has been paid $290,260 since it first started lobbying for the river agency in 2004.

Local politically connected people are also getting big paydays. Political consultant Bryan Eppstein, who has worked on the campaigns of many water district board members as well as those of Fort Worth Mayor Mike Moncrief, is getting a combined $30,000 a month from the water district and Trinity River Vision Authority for a communications/lobbying firm he will head. Included in the duties, according to the contract, are “the development and implementation of legislative and regulatory strategies.” The total worth of the contract, which runs through 2010, is $1.4 million.

Former Texas House Speaker Gib Lewis, who handles lobbying in Austin for the Tarrant district, is budgeted to receive $60,000 this year. Since October 2001, Lewis has been paid $283,500 by the water district. Neither Eppstein nor Lewis returned the Weekly’s calls for this story.

Oliver did not respond to a request for an interview but said in an e-mail that not all the work being done by Eppstein and his Trinity River Communications Joint Venture is lobbying. Eppstein is “assist[ing] us with our Oklahoma and general water-supply efforts,” Oliver wrote. “... The joint venture has many partners, and they are focused on minority contracting and communications.”

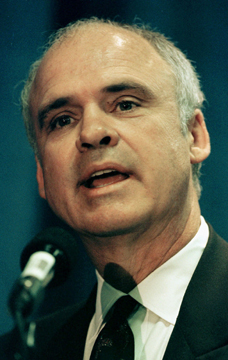

The $120,000 yearly contract with Welch Resources has raised even more questions from critics. Welch is run by former U.S. Rep. Mike Parker of Mississippi, who booked more than $1 million in lobbying contracts last year.

A former funeral home operator, Parker was elected to Congress as a Democrat in 1988, then switched to the GOP when the Republicans took over Congress in 1994. He ran for governor in Mississippi in 1999 and lost. Two years later, President Bush appointed him to oversee the Army Corps, as assistant secretary of the Army for civil works. However, the Bush administration forced him to resign six months later after Parker complained about cuts to the Corps’ budget.

Parker has said publicly that Corps money would be better spent in restoring old levees that have been damaged by time than in taking on new projects. But he told the Weekly that the TRV project fits those criteria. “This project is first and foremost about restoring levees,” Parker said. “But it is also about having a project that brings the community together. This is about using flood control to set up a way for the entire community to have access to the river, and I think every community in the country should have a project like [this].” Asked what value the taxpayers would get from the contract with his company, Parker said, “I served on Appropriations when I was in Congress and know how the Army Corps works. Those are the areas I will concentrate on.”

There’s a possibility, however, that Parker’s lobbying star could be tarnished in coming months, by an investigation into the actions of another of his company’s clients. Two days after Hurricane Katrina struck the Gulf Coast, AshBritt Inc., a Florida-based company, hired Parker to lobby, and AshBritt subsequently got a $1 billion FEMA contract to do storm cleanup. However, the Department of Homeland Security, which oversees FEMA and some Army Corps contracts, is now investigating whether some of the firms involved in the Katrina cleanup (Shaw Group, Bechtel Group, Fluor Corp., among others) overcharged for their services. A half-dozen Congressional Committees are planning hearings in the next few months.

Ellis, from the taxpayers’ watchdog group, said Parker could have problems if the investigation finds that AshBritt overcharged the government. “There could be some carryover,” he said. “People might see him as part of the problem, a former Congressman who is helping to facilitate overspending.”

Overspending is what some think the Tarrant water district is doing these days, thanks in part to income from Barnett Shale gas drilling on district-owned lands, mostly along the Trinity River and its lakes. The agency’s latest financial report showed an operating surplus of more than $24 million — half again as much as the expected annual expenditures for the year. And the $26 million in gas drilling royalties and bonuses that the water district received last year is likely to rise in the future, as the number of wells on district property doubles.

Picht thinks that the district might want to use that money differently. The Tarrant agency “has a main purpose, to get water cheaply and efficiently to the users in North Texas,” he said. “But it seems they are more concerned with spending lots of money to keep this economic development project going. A lot of what they do doesn’t make much sense.”

Steve Hollern, a former Tarrant County GOP chairman, called the TRV a “massive transfer of wealth from private citizens to rich developers.” The lobbying, Hollern said, “is just part of the cost to keep this transfer going. But I have to give the devil his due. They plan and execute behind the scenes in ways that would make Machiavelli take notice.”

Email this Article...

Email this Article...