In ‘Noah’s Ride,’ a Western about a slave’s escape to freedom, 13 North Texas authors take turns advancing the story.

In ‘Noah’s Ride,’ a Western about a slave’s escape to freedom, 13 North Texas authors take turns advancing the story.

|

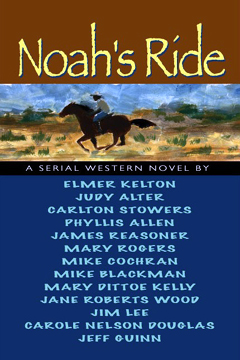

| Noah’s Ride: A Collaborative Western Novel, by 13 authors\r\nTCU Press, 2006\r\n176 pps.\r\n$19.95 |

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Posse Prose

A bunch of Fort Worth scribes collaborate on a Western that hits more often than it misses.

By BETTY BRINK

At least it’s not called Naked Came the Slave.

A baker’s dozen of Texas writers have set egos — and some might say common sense — aside to write a collaborative novel (which might be better described as a novel of unexpected outcomes) about the adventures and misadventures of a runaway slave near the end of the Civil War. They chose a genre that first found financial success but was royally panned by critics for good reason. In 1969, a bunch of Newsday staffers got together to write Naked Came the Stranger, an intentionally witless novel filled with kinky sex and little else, as a social experiment to see if the public would buy it and, if so, to prove just how low Americans’ reading habits had sunk. It sold like gangbusters. Case closed.

The collaborative novel continued, with a slew of Naked Came the (fill in the blank) books, none of which reached the financial success of Stranger.

Following a series of flops, the genre eventually grew dormant, but it has recently been revived in Cowtown, with the publication of Noah’s Ride. Successive chapters are written by different authors, few of whom are, um, strangers to the reading public here: Elmer Kelton, Judy Alter, Carlton Stowers, Phyllis Allen, James Reasoner, Mary Rogers, Mike Cochran, Mike Blackman, Mary Dittoe Kelly, Jane Roberts Wood, James Ward Lee, Carole Nelson Douglas, and Jeff Guinn. Many are award-winning authors whose books have headed various best-seller lists. This collaborative effort was the brainchild of the late Fort Worth Star-Telegram travel editor Jerry Flemmons, who pitched the idea about 10 years ago to a bunch of his writing buddies who met from time to time in the TCU Press office, according to an editor’s note by Alter, the director of the press. After Flemmons died, the project stalled. It was revived last year by members of the group. The writers chose a basic plot, and they were turned loose.

Each author’s job was to advance the story where his/her predecessor ended a chapter — and keep the suspense alive. Surprisingly, everyone in this gaggle of writers, all pros except for Kelly, who won a Star-T writing contest for the privilege of penning a chapter, pulls it off, although some chapters are much better than others. Noah is not the Great American Novel, but it’s a satisfying one-night read and a page-turner, in part because of simple curiosity about where the next writer will take the story. No question, it’s over-the-top melodrama with a helluva lot of gore — murders, rapes, an attempted lynching, even a baby kidnapping. Racism, of course, runs through it as dark and menacing as the waters of the Mississippi that Noah, a slave with no last name, must cross on his run to freedom.

The trite plot comes straight from a 1950s potboiler: Noah is young, strong, angry, and hell-bent on escaping the brutality of the Ellerbee plantation where he had been sent as a young boy after being sold away from his mother and sister, the memory of his mother’s screams still in his head. He is known as much for surviving the brutal lashings he gets each time he is caught as he is for his continued attempts to escape.

Plantation owner Ellerbee (with no first name) lets his “weak-minded” giant of a slave Goliath, the enforcer of “massa Ellerbee’s law” and his number-one breeding machine, give Noah the lash, but always stops him from killing Noah. Ellerbee doesn’t want to lose Noah. He’s too good a worker and a potential breeder of more strong slaves. He wants to tame him, but Noah won’t be corralled. He finally escapes, for the last time, following a confrontation over a young female slave that leaves Goliath laid out on the floor of a slave cabin with a butcher knife deep in his chest. Noah runs, heading for Texas, and Ellerbee calls in one of the meanest-drawn characters in fiction, slave catcher Quint, with a “milky eye,” to track him down. Ellerbee now wants Noah dead because Goliath’s demise has deprived him of a valuable possession — “a real money-maker,” he tells Quint.

With $100 in hand and a promise of another $100 when he brings Noah’s head to Ellerbee on a platter, Quint sets out. History, however, is about to overtake them all. It is 1863, and the siege of Vicksburg is about to begin. The Yankees are camped just across the Mississippi River in Louisiana. And so the saga of Noah’s ride begins.

There are some truly outstanding chapters, particularly the ones that were written by award-winning authors Kelton (the plot-setting author of the first chapter) Stowers, Wood, Douglas, Rogers, Cochran, and Blackman. They made this reviewer wish those seven had cooked the whole enchilada.

Cochran and Blackman, the first a longtime award-winning Associated Press reporter and author of books about Texas murders, and the second the Star-T’s one-time executive editor, produce the most fun reading. They introduce two characters right out of a B-Western, the Buck brothers, Derwood and Doodad; a sad lady who rocks all day on her porch watching for the husband who never returned after “taking a herd to California”; and shoot-outs at the Cactus Saloon in Saint Angela (now San Angelo) where, it is highly conceivable, these two crusty old journalists wrote their chapters over a cold one or two.

Kelton, author of The Time It Never Rained, Two-Bits A Day, The Good Old Boys, and The Smiling Country, all of which made various Western fiction bestseller lists, has a lifetime achievement awards from The Texas Institute of Letters and the Western Writers of America. His opening chapter is clearly the best, and he sets the standard high. Stowers, a former reporter for the Dallas Observer, is a writer of true crime books and has twice won the Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America. Douglas is the author of 50 mystery novels and also the winner of many awards. Wood wrote the classic Train to Estelline. Rogers, best known for her society columns and Star-T features, does a surprisingly good job writing about Reconstruction, the slow awakening of blacks to their new rights, and the rise of the Klan. Along with Blackman and Cochran, these writers met Kelton’s challenge. Unfortunately most of the others fall short.

Guinn, whose job it is to tie it all up, disappoints. Following a tale filled with enough human tragedy for a dozen Greek plays, the former Star-Telegram book editor shows why his one bestseller is about Santa Claus. His ending is trite and Pollyannaish, not at all worthy of what went before. But still, what went before is worth the read.

Email this Article...

Email this Article...