The title character of Mike Nichols’ novel is a sort of Everyman for an Everysmalltown.

The title character of Mike Nichols’ novel is a sort of Everyman for an Everysmalltown.

|

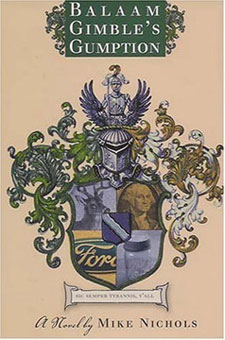

Balaam Gimble’s Gumption,

by Mike Nichols

John M. Hardy Publishing

$23.95

300 pps. |

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

The Simple Life

A hayseed with a brain is at the center of former daily newspaperman Mike Nichols’ debut novel.

By STACY SCHNELLENBACH BOGLE

As strange as this may seem, the words “literary” and “Fort Worth” can be used in the same sentence. This city is crawling with the bound work of historians, biographers, and novelists, many of whom got their starts as newspaper writers. Jerry Flemmons, Hollace Ava Weiner, Mike Shropshire, and Gary Cartwright. Elston Brooks, Tim Madigan, Leonard Sanders, Larry Swindell, and Rich Haddaway. Many of these names are as familiar to local newspaper readers as a morning cup of coffee, and a few of those wordsmiths — Bud Shrake, Dan Jenkins— are recognized nationally. No one should really be surprised that the latest addition to this august company is former Fort Worth Star-Telegram columnist and humor writer, Mike Nichols, whose debut novel, Balaam Gimble’s Gumption, was published just before Christmas.

Nichols, who has said that the novel represents the most autobiographical thing he’s ever written, also reports that the story was inspired by 25 years of living in Texas outside the big-city limits. The fictional setting of Willoughby is a product of Nichols’ ability to recall small locales and their inhabitants’ desire to enjoy the unhurried lifestyle of a small town while making a decent living — often a nearly impossible combination. In the words of the title character: “Not long after I relocated to a dirt road eight miles from the nearest town in a county with the same number of people it had 100 years earlier, somebody started a sand excavation business down the road. The progress-oriented people would call that good: more jobs, more tax revenue, more money spread around. But the people who moved that far out to be able to hear a bee buzz at 10 feet as it whispers the facts of life in the ears of wildflowers or to hear a hummingbird hum at 20 feet as it tries to remember the words would call it something else.”

Balaam Gimble is a middle-aged, self-employed handyman who lives surrounded by railroad ties, coffee cans full of nails, and sheets of corrugated metal — the homely detritus commonly associated with folks who make their livings with their hands. Affable, courteous, comfortable in his own skin, Balaam seems to enjoy his break-even existence. His monastic one-room cabin, built on land his family has owned for five generations, is merely the means to an end, an opportunity to witness the natural world unfolding from the comfort of his front porch. For Balaam, the land is the point, and that continues to be true even after he discovers an underground spring of health-promoting mineral water on his property and the rest of his neighbors begin finding ways to make their own plans for Balaam’s property and the future Willoughby.

A common mistake among those writing about rural areas is to wring every ounce of common sense from a cast of players, infusing each with his or her own brand of idiocy, thus making room for the bigger laugh at the character’s expense. Simpletons leading the simple life. Unlike some writers who are content to draw country people as caricatures of the typical Southern hayseed, Nichols peoples his book with the kinds of living, breathing folks you’d find in any small Texas community. Run in to the Chigger Ranch Convenience Store in Dublin for a bag of chips and an original recipe Dr. Pepper, and you’ll find the same kinds of characters as those who populate Balaam Gimble’s Gumption.

The novel’s beginning is leisurely, and the reader might begin to wonder when and how things will take off, although that’s most likely Nichol’s intent. Willoughby’s inhabitants do live at a slower pace, as do many folk whose existence depends on how fast okra grows and whether or not it rains.

Nichols says some of the characters are based on real people, others just represent “types,” and altogether they paint a full spectrum — good and not-so-nice, ambitious and content, those who see the town as it is versus those who see it as it once was and could be again. If there is a weakness in the novel’s construction, it is when the lines separating good people from bad are drawn a mite too deliberately. To some of the citizenry, J. Howard Liggett is the urban savior who comes to rescue Willoughby from certain extinction, but to Balaam he’s the harbinger of unwelcome change and relentless opportunism. The reader might know the feelings of each character, but ultimately we view the world through Balaam’s filter.

Balaam Gimble’s Gumption is, nevertheless, a novel of integrity, with a solid premise, believable characters, and cleverly understated dialogue. Nichols has assembled a host of individuals who gladly live in a place where, when you stop to smell the roses, the noise in the background is that of an armadillo rustling through the underbrush — not the roar of gunfire from the neighbor kid’s video game. All in all, a pretty nice place to spend some time.

Email this Article...

Email this Article...