| The videotape from Officer Herod’s car showed the stop (with slightly different times than she gave in her report), but didn’t record the conversation. (The “VIP” license plate shown on the Weekly’s cover is an illustration — not Wheatfall’s actual plate.) |

The chief was working overtime to please a city councilman and quell discontent among his troops. (Photo by Bill Miskiewicz)

The chief was working overtime to please a city councilman and quell discontent among his troops. (Photo by Bill Miskiewicz)

|

|

‘It was inappropriate for the chief to call me on the carpet for a legitimate traffic stop.’

|

The city councilman felt he was stopped because of racial profiling and then dragged through the mud in e-mails. (Photo by Jerry W. Hoefer)

The city councilman felt he was stopped because of racial profiling and then dragged through the mud in e-mails. (Photo by Jerry W. Hoefer)

|

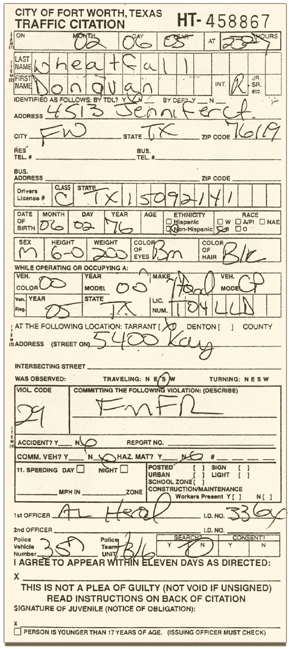

That’s the ticket.

That’s the ticket.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

The Big (Fuzzy) Picture

A touchy traffic stop snowballed into a loyalty test for Police Chief Mendoza — and a disappointment for police rank-and-file.

By JEFF PRINCE

A pebble being dropped into the ocean should have caused a bigger ruckus than the traffic stop that happened in southeast Fort Worth late one night in February. Guy commits a minor traffic infraction, gets pulled over, gets a ticket, gets it dismissed in court a few days later. Not enough to ripple the water in a wading pool.

Except that the driver was a Fort Worth City Council member, who called the police chief, who called the sergeant, who lectured the cop, then regretted it, and in a few weeks everybody in the department had heard some version of what happened. And now you have a wave of rank-and-file anger big enough that it’s soaking at least the ankles of folks at city hall, as officers question the motives of both their police chief and the councilman.

The pebble: Councilman Donavan Wheatfall was driving through a southeast Fort Worth neighborhood at around 11:30 p.m. on Feb. 6 — Super Bowl Sunday — when police Officer Alison Herod pulled him over. He had made a right turn at a stop sign in a residential area without using his turn signal. Not exactly the type of crime that gets a guy’s mug shot hung in a post office. But a dispute with the officer prompted Wheatfall to make a midnight call to police Chief Ralph Mendoza, and before you can say, “License and registration, please,” a brouhaha was brewing among the band in blue.

Wheatfall figured he had been racially profiled and was sure he had been treated without due respect. Police officers wondered if Wheatfall had used his political clout to try to get a good cop in trouble, and whether the police chief took the elected official’s side without hearing his own officer’s side, and then crossed the line further by suggesting that influential people shouldn’t be ticketed. (The chief completed the circle by then complaining about the officer’s hair length.) The city, meanwhile, did its typical job of trying to discourage media scrutiny by charging Fort Worth Weekly more than $400 to recover less than a month’s worth of e-mails from a few city employees.

More information: Several months later, Wheatfall says the situation was misunderstood. The city sort of defends its exorbitant fees for public information. The cops are still peeved at Mendoza. And the chief isn’t talking, other than to dub the matter a “minor and trivial issue” that doesn’t deserve addressing. Maybe so — but if it were so insignificant, why would he call a sergeant at 1 a.m. to discuss the matter, and why would the chief’s troops be so teed off? Regardless, the East Side Showdown on Super Bowl Sunday makes for a more compelling clash than the one held on national t.v. this year.

A 2000 Honda Accord coupe was eastbound on Sun Valley Drive, moving slowly. It was 11:17 p.m. on a Sunday. The driver was talking on a cell phone and didn’t notice the police car behind him. Police Officer Alison Herod ran a license plate check and noted that the car was registered to a Hurst address. When the Honda’s driver pulled up to a stop sign and turned right onto Kay Drive without using a turn signal, Herod hit her emergency lights. The neighborhood is no slum, but it’s lined with inexpensive homes and sees its share of revelry.

Inside the Honda, City Councilman Donavan Wheatfall was confused. He didn’t recall doing anything wrong, he wasn’t speeding, he was cruising through his own district, just as his predecessor Frank Moss used to do when he represented this southeast Fort Worth neighborhood.

The day had been a busy one. Wheatfall and his wife had watched the Super Bowl earlier that evening at the home of a legislator friend, Rep. Mark Veasey, D-Fort Worth. Afterward, Wheatfall had gone to Starbucks for a caffeine-assisted review of his council packet in preparation for the next week’s council session. On his way home, he said, he turned down Sun Valley Drive to look at the site where a new housing development was about to be built. He was chatting on his cell phone, still in dutiful city councilman mode, when a police officer’s flashing lights suddenly filled his rearview mirror.

When he decided to run for office, Wheatfall had moved from Hurst back to his old stomping grounds in east Fort Worth, and now he realized his car was still registered under his old address. He wondered if driving a nice car in a poor neighborhood had aroused police suspicion. There’s a reason that African-Americans only half-jokingly refer to the “crime” of DWB — driving while black. A city report on racial profiling, released the following month, showed that Fort Worth police are more likely to stop and arrest people in poor communities. The report, required by Texas Senate Bill 1074 and based on 2000 data, showed that African-Americans were stopped 33 percent more often than they should have been based on their percentage of the car-owning population (referred to as the “baseline”).

“There is a demonstrative gap between African-Americans and their white counterparts as far as tickets, arrests, un-consented searches,” Wheatfall said. “As a councilperson I have to be diligent as far as setting a tone on how we effectively fight crime — but at the same time, are we being oppressive in poor communities?”

The report included some eye-catching figures: Hispanics were searched at a rate slightly above the baseline, while African-Americans were searched at a rate of 64.6 percent higher than statistics suggested they should be. And in cases where a traffic stop led to a search, African-Americans accounted for 42.3 percent of those searched. Despite general orders and Mendoza’s declarations against racial profiling, Fort Worth police obviously are more likely to stop Hispanics and African-Americans — even though whites make up more than half of the households with vehicles, compared to 21 percent for Hispanics and 19 percent for black households.

Wheatfall’s car windows were tinted and it was dark, so he doubted the police officer could have known his race, but “the neighborhood played a definite factor” in his being stopped, he believes.

Like most people in similar situations, he didn’t enjoy being flanked by a cop on the side of the road.

“It’s an intimidating state to be in the car with these glaring lights, bright gleaming search lights on behind you,” he said. “My car wasn’t stolen. I didn’t have any warrants for my arrest or flags on my license.”

He sat and waited. Herod, a 34-year-old white woman with two years of experience as a cop, approached his window and asked for his driver’s license and proof of insurance. Wheatfall complied but also wanted to know why she had stopped him. From there, the conversation became strained, and the two accounts vary.

Wheatfall said he purposely avoided identifying himself as a city councilman because he wanted to see how a regular resident in his neighborhood might be treated during a traffic stop. He also felt that it was his right to know why he was being stopped, and he said the officer was rude.

In a report to her supervisor, written the next day, Herod described the scene differently. “The driver asked why I had pulled him over, and I explained to him that once he gave me his license and insurance I would then tell him,” she wrote. “The driver seemed hesitant about giving me his information, which I found odd.”

Wheatfall handed her a driver’s license and a plastic card that identified him as working for the city council, Herod said in her report. “I asked what he did, and he said he was the city councilman for this district,” she said. “I asked if he had a copy of his insurance, and he looked around the vehicle for a second, then looked at me and said he didn’t have it.”

She walked back to her car, still without telling him why he had been stopped. Herod didn’t know who the council member was for the district and called another officer to verify Wheatfall’s identity. She also ran a check on his driver’s license and saw that he had been ticketed in 2002 for not having proof of insurance. “During any routine traffic stop I take the driver’s history ... into consideration,” Herod wrote. “A previous ticket or tickets for FMFR (failure to maintain financial responsibility) shows a lack of understanding for the importance of carrying insurance on the vehicle. Routinely, I will write a ticket for FMFR, knowing that if the driver has insurance it will generally be dismissed” by a judge in court.

Herod issued a ticket. “I decided that it would be best to treat this traffic stop like any other traffic stop,” she wrote. “I wrote him the ticket for FMFR, but I did not write a ticket for no turn signal.”

When Wheatfall returned home, he called Mendoza. Nobody is privy to the conversation except those two men, and Mendoza won’t discuss it. That leaves Wheatfall’s account. He justified calling the police chief at almost midnight on a Sunday, saying that, as a city councilman, he, too, gets calls at all hours. Wheatfall said he asked Mendoza if he had been sleeping. The chief said he had not been asleep, but was up and working at his desk.

Wheatfall said he wasn’t angry when he called the chief. “I wanted to know: What was the policy of the city of Fort Worth in detaining a citizen and not telling them why they were being detained?” he said. “I live in a very impoverished community. I was raised there and live there by choice. There is a fine line between police enforcement and police harassment.”

Wheatfall said he didn’t tell the police officer he was a city councilman until the very end of the traffic stop, which stretched almost 10 minutes, based on videotape recorded from the police officer’s squad car. Herod, though, said Wheatfall immediately identified himself as a city councilman. The squad car’s audio was turned off and didn’t capture their conversation on videotape, something that perturbs Wheatfall.

“One of the ways we begin to solve this problem is we need to make sure that those audiotapes are running,” the councilman said. “That way if police officers are doing their jobs, they are vindicated. If they are not doing their jobs, then due discipline should be taking place.”

If the audio had been turned on, “you would have seen an officer who was abrupt and rude and cut me off in the middle of me asking the reason I was being detained,” he said. “When I asked her why I was being stopped, she said, ‘I’ll get to that in just a moment; let me have your driver’s license and insurance.’”

The chief explained that police don’t have a definitive policy but that most officers will explain up front why they have pulled over a motorist, Wheatfall recalled. “He said it dispels any preconceived notion of [police officers] not having a reason to stop them,” he said.

He also recalled Mendoza saying he would have handled the stop differently than the officer. “He said, ‘I’ve seen your car and I’ve seen you, and if that was me, I would have just given you the information, but I don’t know what was going on in the mind of the officer,’” Wheatfall said.

After the phone call ended, Mendoza then called Herod’s direct supervisor, Sgt. Russell Johnson, for a conversation that lasted about 30 minutes. A police source who asked for anonymity for fear of reprisal from the supervisors said the chief instructed the sergeant to counsel his officers on “why you don’t cite city council members.” Mendoza also asked for a copy of the videotape. “This is unusual,” the source said. “It’s not unusual to pull a video if there is a formal complaint, but most complaints aren’t taken in the middle of the night directly to the police chief. It’s unethical for the police chief to tell you not to practice fair enforcement.”

The sergeant sent an e-mail to Mendoza at 1:34 a.m. on Feb. 7, saying that he had sent the video to the chief via inter-office mail, along with Herod’s explanation of what happened. “I counseled with her concerning the use of one of our more powerful tools as police officers, with that being officer discretion,” Johnson wrote. “We had a substantial conversation about the ‘big picture’ when it comes to those in power whom we need on our side politically. She advised me that in the future her courtesy and discretion would be more forthcoming.”

Johnson, a sergeant on the late-night shift, sent a copy of his e-mail to his supervisor, Lt. Daniel Humphries. When the lieutenant got in later that morning, he responded, writing to the sergeant that he understood the chief’s reason for counseling with Herod about discretion, but adding that “it should be clear that she did nothing wrong either.” The lieutenant then had a few choice words regarding Wheatfall. “The thing that gets me is the nerve of a councilman to call the police chief and wake him up at midnight because an officer enforced the law,” Humphries wrote. “If he wasn’t in violation or if the officer was rude would be one thing, but to get upset because you (a mighty councilman) was issued a ticket is another. I would have loved to have heard that the chief asked Mr. Wheatfall if he was in violation and if the officer acted professionally, and hearing this was the case, telling Mr. Wheatfall how he could handle the citation like anyone else.”

Humphries also commented that police training involves being asked what an officer should do after stopping an influential member of the community. The candidate is supposed to respond that they would handle the situation as they would any other stop. “Obviously, we shouldn’t use that question,” Humphries wrote, insinuating that it is hypocritical to use that scenario during oral review boards if the unspoken policy is to do the opposite.

Later that night, Johnson was back on the third shift. At 10:46 p.m. he wrote an e-mail to his lieutenant, saying that he conducted staff training on the situation during roll call. He expressed remorse about his conversation with Herod. “I retracted my statements to Officer Herod that I made last night,” he wrote. “After stewing on it all day, I feel that it was inappropriate for Wheatfall to call the chief because of who he is, and it was equally inappropriate for the chief to call me on the carpet for a legitimate traffic stop with a legitimate citation.

“Wheatfall’s complaint to the chief was that Herod was rude and racially profiling him because of his race,” he continued. “The last part is ludicrous, and apparently he thought she was rude because she wouldn’t tell him why he was pulled over until he gave her his identification. As a matter of law, we are not required to inform the citizen as to why we are pulling them over. It is simply a courtesy we offer them. As a matter of officer safety, it is much better to get their identification as quickly as possible in order to know who we are dealing with.”

Traffic codes require motorists to provide police identification upon request.

“I apologized to Alison [Officer Herod] for telling her not to write any more tickets to city councilmen, and we openly discussed the difference between a decision made politically and one made ethically,” he wrote. “I explained to the troops that the ethical decision should always outweigh the political one and that I would stand behind them should they use their officer discretion and write the ticket.”

When discussing the racial profiling accusation with his officers, Johnson said, “If everyone is treated equally across the board, then the race card can not be played.”

He ended the e-mail with a shot at Mendoza: “I am disappointed that the chief put me in that pickle to begin with.”

Lt. Humphries agreed with Johnson and sent a confidential e-mail explaining the situation to police Capt. Gianni Ghilespi, who also sided with Johnson and Herod. Ghilespi’s e-mail made a pointed reference to Wheatfall. “Politics aside, [Herod] was just doing her job. I believe it is insight to the maturity level and character of Wheatfall to call the chief at all, let alone at the hour described. He should be embarrassed for not having the required document with him.”

To further show support for Herod, the sergeant compiled statistics regarding the officer’s work productivity. Herod consistently wrote a large number of tickets, yet received few complaints. In 2004, she made 771 traffic stops without having a complaint filed against her involving rudeness or abrasive behavior. Johnson sent the stats to Humphries, who passed them on to Mendoza and told the chief in a Feb. 8 e-mail that Herod’s decision to write a ticket was consistent with her past actions. “The complaint of rudeness or racial profiling is definitely not consistent with her performance,” he wrote. “I think if this was characteristic of her behavior, complaints would be forthcoming,” given her high rate of ticket-writing.

Johnson also sent the stats to Mendoza, along with a comment on Wheatfall. “It is my feeling, after reviewing all of the available facts and interviewing Officer Herod, that Councilman Wheatfall was upset because he received a citation, which he thought he should not have, and projected his frustration onto my officer.”

The next day, Mendoza sent a brief e-mail to Johnson and copied the message to Johnson’s direct supervisors. It wasn’t one that calmed the waters. “Did you purposely allow Officer Herod to violate the GO’s [general orders] in regards to hair standards?” Mendoza wrote. “In reviewing the tape I noticed she was wearing a ponytail, and it went below the lower part of her uniform. Lt. Humphries, please handle this issue with your sergeant and advise me on how it was handled.”

Humphries wrote back the next day saying that he had told Johnson to cover the hair issue with staff, and placed the general order on hair length on display for the troops.

Mendoza responded: “If you care enough about your officers, you will keep them from doing things that could get them hurt. On this hair issue, the ponytail is a great tool for a suspect to use against our officer.”

Those were fighting words to some officers and more evidence that the chief was being petty with his troops. “This is a real hard-working officer,” said the police source who requested anonymity. “This is not one of those bad officers who slam- dunks everybody and gets complaints all the time. In this case, working over that area of town and working the midnight shift, you are going to be checking out people and stopping people and trying to roll the stones over and find out what is going on.”

Fort Worth Police Officer’s Association President Lee Jackson defended Herod and her stop of Wheatfall. “The officer who works that part [of town] at midnight has done an extraordinary job,” he said. “She is very productive in her district and has not had any racial profiling complaints. Traffic stops are one of the cornerstones of good police work. She did nothing wrong and had probable cause to make a traffic stop. The last thing we want to do is discourage what she was doing, which is good police work, people doing their jobs, taking care of our communities.”

The anonymous source said Wheatfall was out of line: “What reasonable person calls the chief in the middle of the night to rant and rave? Most people would wait until the next day.”

But the troops might have been jumping to conclusions about Wheatfall’s reaction and how he expressed them to the chief. By coincidence, Jackson and Wheatfall had planned a meeting on the Monday following the city councilman’s ticket. The two discussed the traffic stop, and Jackson recalled that Wheatfall was calm and collected. “I talked to him the next day after it happened, and he expressed to me that he understood completely why the officer had stopped him,” Jackson said. “He was very nice about it.”

Later, niceness would give way to agitation when Wheatfall learned he was the punching bag amid all the e-mail bantering and speculation among police officers. “You can see the type of conversations that were going on in the public domain which I thought were inappropriate,” he said. The incident left him feeling compelled to stand even more firmly against racial profiling and other potential abuses against the people in his district. “As a new city council member, I’m learning more and more what my position is as far as protecting the interests of common people,” he said. “We don’t want to oppress people who are already poor.”

Suddenly, the chief seemed to become aware of a potential hot potato in his hands. His troops were accusing him of being unethical, and they were making assumptions about what was said during the midnight conversation with Wheatfall. Rumors and e-mails were flying fast and furious.

Damage control was on the way.

On Feb. 8, the police chief sent an e-mail to department supervisors, addressing the growing discontent over how he had handled Wheatfall’s midnight complaint. Mendoza admitted no fault and cautioned supervisors about being overly staunch in their support of an officer when nobody had done a full investigation of the incident. (As opposed, one might note, to what Mendoza himself did, when he appears to have supported Wheatfall after his late-night call without first getting the officer’s side of the story.)

Another lengthy e-mail that same day, from Mendoza to police supervisors revealed a bit of exasperation. Writing to Ghilespi, Humphries, and Johnson, the chief tried to downplay the situation. “You guys are making too big of an issue about this,” he wrote. “As I indicated to Sgt. Johnson the night we talked, I had no problems with [Herod’s] stop, and I did not want her spirit broken.”

He said Herod was “within her authority” to make the traffic stop and that Wheatfall was only concerned that the police officer “reacted inappropriately” when he asked why he had been stopped.

“Her response to him seemed as though she was put out by the request and responded very abruptly and to the point of telling him something to the effect of just give me your driver’s license,” he wrote.

He reminded them that the sergeant spoke with Mendoza on the night of the incident, but had never spoken with Wheatfall, so none of them should be making assumptions about what the councilman said. “Again, as I told the sergeant, don’t quote what I have said as a direct quote of the councilman,” Mendoza said.

Police officers had been grousing that Mendoza appeared to have been more interested in getting cozy with a politician and thinking about “the larger picture,” as he described it, than in supporting an officer who was doing her job. Mendoza said he hadn’t expected Herod to be disciplined, only counseled. “I did ask that Sgt. Johnson check into the situation and handle it as a coaching, counseling, and training with the officer,” he wrote.

The intensity with which the supervisors were supporting Herod indicated that they were accusing Mendoza of selling her out, and the chief responded to that. “I am a little perplexed that you seem to have the need to say you are standing behind your officer,” he said. “First, I have not seen any indication by anyone, including myself, that has not stood behind your officer. Second, be careful how far you go in that regard without a full-blown investigation.”

Then, he listed his expectations of officers: “I expect our officers to be nice, polite, well-mannered, courteous, professional but firm,” he said. “I expect our officers to treat all people with dignity and respect. If we do, then in most cases, we will receive dignity and respect back from those individuals with which we deal.”

After elaborating on the merit of training and self-improvement, he seemed to support Wheatfall’s version of the situation and question whether Herod used proper discretion or whether she might have issued the ticket simply because she was irritated by the councilman’s question. “If this discretion is used in an inappropriate manner, then we as officers are wrong,” he said. “If we use it to write someone a citation because a citizen asked a simple question of why they were stopped and that antagonized our officer, then we are wrong. We should not use our positions of power and authority to punish a citizen when they asked a very legitimate question.”

A legitimate query is what the Weekly figured it posed to city officials a few months later. Trying to use public records to reconstruct this story, the Weekly asked for e-mails and police documents regarding the incident — but public records aren’t always easy to get in Fort Worth. While investigating a police officer last year, the Weekly requested three years’ worth of e-mails from a police lieutenant. The city claimed it would take 20 hours of labor at $15 an hour and three to four weeks to process. An assistant city attorney explained that once e-mails are more than six months old, it is more time-consuming and difficult to retrieve them. The Weekly then pared back its request to e-mails written in the previous six months — and the city’s estimate for this seemingly much simpler search was virtually identical to the first figure.

When the Weekly heard about the controversy regarding Wheatfall and Mendoza, it also learned of the flurry of e-mails — in which, the source said, the chief seemed to be sending the message that politicians shouldn’t be given traffic tickets. If true, it sounded like information that would benefit the public — and thereby qualify under state law for a reduction or waiver of fees.

The Weekly requested three weeks’ worth of recent e-mails from six employees. The city said the request would require 27 hours of labor at $15 an hour, or $405. A Weekly reporter called the city attorney’s office and asked for an explanation of the high cost. The reporter was directed to call Alton Bostick, senior technical support analyst — but Bostick didn’t want to talk to the media. Six days, two unreturned phone calls, and an e-mail later, a staffer at the city attorney’s office called to say she had forwarded the Weekly’s questions to Assistant City Attorney Melinda Ramos. By press time the following week, Ramos had not responded with any explanation.

The e-mails — including those quoted above — were eventually produced, however. They showed Mendoza, to the end, trying to please everyone.

“Now, I have taken some time, albeit perhaps not enough, to give each of you some coaching, counseling, and training,” he said. “You cannot blindly protect our officers without having all of the facts. If we had a video and audio recording, then we would be in a more solid position to determine what occurred.

“I hope each of you see a much larger picture,” he wrote. “[I]f not please feel free to set up a meeting for further discussion.”

Email this Article...

Email this Article...