| Feature: Wednesday, November 05, 2008 |

After the 1900 Storm, Galveston built the 17-foot seawall that protected it for the next century.

After the 1900 Storm, Galveston built the 17-foot seawall that protected it for the next century.

|

The good craft Tranquilo obviously had a pretty untranquil time thanks to Ike, ending up on a sidewalk near the UT Medical Branch. Photo by Chris Pierson.

The good craft Tranquilo obviously had a pretty untranquil time thanks to Ike, ending up on a sidewalk near the UT Medical Branch. Photo by Chris Pierson.

|

The coastal town of Gilchrist, shown in before and after photos, was devastated by Ike, literally losing ground as well as whole streets of houses. Top photo courtesy Googlemaps.com, DigitalGlobe, GeoEye, Houston-Galveston Area Council. Bottom photo courtesy National Geodetic Survey.

The coastal town of Gilchrist, shown in before and after photos, was devastated by Ike, literally losing ground as well as whole streets of houses. Top photo courtesy Googlemaps.com, DigitalGlobe, GeoEye, Houston-Galveston Area Council. Bottom photo courtesy National Geodetic Survey.

|

This badly damaged beach house still fared better than many buildings. Some cannot be rebuilt, due to beach erosion caused by the storm. Photo by Chris Pierson.

This badly damaged beach house still fared better than many buildings. Some cannot be rebuilt, due to beach erosion caused by the storm. Photo by Chris Pierson.

|

The U.S. Coast Guard helps clean up storm debris near Pier 21 on Galveston’s bayside. Photo by Chris Pierson.

The U.S. Coast Guard helps clean up storm debris near Pier 21 on Galveston’s bayside. Photo by Chris Pierson.

|

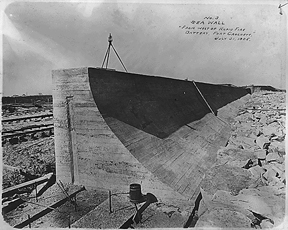

The 1900 Storm killed more than 6,000 people on Galveston Island. Photo courtesy the Library of Congress.

The 1900 Storm killed more than 6,000 people on Galveston Island. Photo courtesy the Library of Congress.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

A Tale of Two Storms

Galveston’s Seawall Became Its Maginot Line

By Tom Curtis

I’ve lived about half my life in a city that shouldn’t be there. In local parlance, I am a B.O.I., meaning that I was born (during a hurricane, no less) on Galveston Island. It’s where I went to public schools and the place to which I returned after a career in Texas journalism.

It’s also the resort town where hundreds of thousands of my fellow Texans got their first glimpse of the sea and had their first beach experience: the pink granite jetties and rented umbrellas, the motels and time-share beach houses. Folks remember buying just the right souvenir t-shirt or seashell at Murdoch’s Pier, eating out at Gaido’s or dozens of humbler spots, checking out the blocks of shlock along the Strand, the city’s reclaimed bayside commercial district. And of course, splashing, wading, tanning, and getting carcinogenic sunburns on the beach.

Before 1957, when the Texas Rangers shut down the wide-open town for its flagrant sins, Galveston was where thousands of my generation’s parents came to imbibe (back when selling liquor by the drink was a crime in Texas), take their chances at the craps tables and roulette wheels (still verboten), and enjoy the floor shows at the swank Balinese Room and tony Hollywood Dinner Club — casinos that periodically featured the era’s big bands and headliners like Frank Sinatra, Bob Hope, and Peggy Lee.

Despite its rich and storied history, confederate jasmine-and-oleander-scented charms, 28 miles of public beaches and summertime bath-tub-warm Gulf of Mexico waters, and a treasure trove of Victorian architecture, Galveston has one irremediable flaw: 169 years ago, it was incorporated on the shifting sands of a barrier island.

As coastal geologists explain, the natural order of things is for these slightly elevated sandbars to roll over, inch by inch, foot by foot, from seaward to landward as every breeze and gale blows sand inland. Hydrologic processes ranging from tides and thundershowers to leviathan storm surges also are changing the island’s features, rebuilding beaches and dunes farther inland.

Because they are in constant, if slow, motion, barrier islands are inhospitable places to build cities — or even beach houses. That, plus their natural propensity to flood — now intensified due to gradually rising sea levels — is why the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change strongly opposes infrastructure development on barrier islands. As the Gospel of St. Matthew recapitulates the age-old wisdom, only fools build their houses on sand.

Long before the UN panel or indeed the United Nations was constituted, nature itself unsuccessfully tried to teach Galveston the lesson of its vulnerability and impermanence. On the second weekend of September 1900, a monster storm that today would be classified as a Category 4 hurricane blindsided and devastated the island city in what is still the deadliest natural disaster in American history. Arguably the second-most confidence-shattering event in Galveston’s history, and certainly the most damaging storm to hit since then, was 2008’s Hurricane Ike on another September weekend. Both times, the storms hit just as the city was building toward a chest-puffing era of prominence or opulence. In both cases, pride went before the fall.

Here’s the dirty little secret about Galveston’s two most devastating storms: Long before the 1900 hurricane and again, decades before Ike, the community’s political leaders were warned of the dangers and advised how to mitigate them — yet they did nothing. In this era of worldwide climate disruption, these are sobering and cautionary tales for us all.

This time, thanks to modern meteorology, the mayor was able to order a “mandatory evacuation” of the city two days before the hurricane hit, and an estimated 60 percent of Galvestonians and virtually everyone at the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (the city’s largest employer) were gone by the time the storm hit. For that reason and because the storm surge on most of Galveston Island was only 13 to 14 feet rather than the predicted maximum of 25 feet, only a handful of people on the island died, many because their medical conditions were aggravated by the loss of electricity. But flooding was intense, afflicting four-fifths of the city’s structures.

Across the bay on Bolivar Peninsula, the storm surge flattened the fishing village of Port Bolivar and wrecked the resort community of Gilchrist as well as many vacation homes on West Galveston Island and homes and businesses in Bacliff, Kemah, and Seabrook. The storm also mangled popular Galveston tourist attractions such as Moody Gardens and the Schlitterbahn water park. Only Moody Gardens has reopened.

Meanwhile, in Chambers and Jefferson counties alone, Ike killed an estimated 10,000 cows and calves, according to Monty Dozier, southern regional program director for the Texas AgriLife Extension Service. Hundreds of acres of pastures were damaged by the saltwater flooding, and Dozier estimates that it may take them from six to 18 months to recover.

Rice farmers were hard hit. In Chambers County east of Houston, an estimated 5,000 to 7,000 acres were inundated, said Thomas Wynn, director of market development for of the Houston-based U.S. Rice Producers Association. Collectively, one industry expert said, the storm easily will cost Texas rice farmers millions of dollars, and the salty soil may cause trouble for several growing seasons to come.

Ike also caused “tremendous habitat destruction” for birds, said Winnie Burkett of the Houston Audubon Society. Two days of saltwater inundation across tens of thousands of acres have wiped out virtually all the insects, plants, and seeds that migrating birds live on.

Some stretches of beaches roiled by Ike may be gone forever, and some Galveston neighborhoods may never be rebuilt. Even Broadway, the grand old tree-lined avenue that runs down the middle of the island, is still a scene of dead-looking live oaks in the median and uncleared wreckage and devastation.

This sad state of affairs prompted lawyer and Texas Senate candidate Joe Jaworski, a Democrat and former Galveston city councilman, to pose in front of these piles of storm refuse for his latest TV campaign ads. Responsibility for maintaining Broadway — the southern terminus of I-45 — rests with the state, which clearly had dropped the ball.

And if you didn’t know a lot of that — if you assumed that this storm, like so many others, had come and gone, causing only some minor flooding and broken windows and ripped-off roofs — well, that’s what a lot of officials are hoping you’ll think. People in Washington, D.C., and at the governor’s office in Austin aren’t eager for Texans to realize the extent to which the Galveston and the coast they’ve known and loved is damaged and changed, perhaps forever.

Before Sept. 9, 1900, Galveston was Texas’ fourth-largest city, a fast-growing metropolis of nearly 38,000 people perched on the east/northeast end of Galveston Island. It was a thriving resort, a center of banking and commerce, and the most important U.S. commercial port between New Orleans and San Francisco. Galveston wanted to be seen as the Manhattan of the Gulf. The city boasted more millionaires per capita than Newport, and it aspired for the Strand, its financial heart, to be recognized as the “Wall Street of the South.”

But Galveston’s fin de siècle economic boom and particularly its burgeoning tourism industry had already produced the seeds of the city’s near-destruction. “In its natural state,” said the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in a history of the island’s seawall, Galveston’s gulf shore “was bordered by an area of sand dunes rising to heights of 12 to 15 feet above the natural surface of the island.”

The dunes protected the island from hurricane tides, the Corps history said, but by the late 1800s, development had led to removal of the dunes. The resulting danger “was realized by many people, and several plans for storm protection had been had been developed; however, because of financing difficulties and general public apathy, none of these plans was carried out.”

In other words, the storm’s huge death toll and devastation was not entirely a natural disaster but also an environmental one, aided and abetted by human shortsightedness, avarice, and criminal stupidity. Much of the hurricane’s carnage was entirely predictable and could have been avoided, but Galveston’s wealthiest citizens thought it cost too much, and the public cared too little. What did American poet and philosopher George Santayana say about those who fail to learn the lessons of history being condemned to repeat them?

The 1900 Storm’s 15- to 20-foot tidal surge drowned 6,000 to 8,000 people, demolished 3,600 houses, cut the city tax rolls in half, and put Galveston in the history books in a far different way than its leaders had hoped. Afterward, the Corps of Engineers designed and constructed a three-mile-long, 17-foot-high seawall that protected the most densely inhabited part of the island from the worst effects of storms for many years. Meanwhile, Galvestonians undertook a heroic project to raise the island’s grade, jacking up existing buildings and pumping in fill beneath them. The resulting elevation was sloped so that any storm water from the Gulf that overtopped the seawall would flow northward downhill to Galveston Bay. The seawall was later extended to 10 miles, but its effective height was eventually reduced by two feet, due to subsidence from the extraction of oil, gas and water beneath the island by a newer generation of robber barons.

After 1900, Galveston eventually revived and rebuilt, growing modestly to a peak of around 60,000 residents in the early 1960s. But it never achieved its earlier ambition and never became a major Texas city or regional financial center. Commenting on its 19th-century architecture, saved largely because of the island’s ensuing economic stagnation, the novelist Edna Ferber once memorably compared Galveston at mid-20th century to a fly encased in amber.

City leaders apparently had another chance to bolster their island’s defenses. According to a recent article in Galveston’s Daily News, the Corps of Engineers in 1979 had described in detail the possibility of a dangerous storm very much like Ike and had recommended a federally subsidized solution: a 12.5-mile ring levee system, up to 19 feet high, running from the ends of the Galveston seawall north and curving back along Harborside Drive. Essentially, this would have encircled the southwest and northeast flanks and rear of the parts of the island unprotected by the seawall. That proposal, with an estimated cost at the time of $94 million, was strongly backed by long-time U.S. Rep. Jack Brooks of Beaumont, the powerful congressman who represented Galveston and chaired the Government Operations Committee. For that reason alone, the then-Democratic Congress almost certainly would have passed it.

But the plan required Galveston County to pick up 30 percent of the tab, plus providing a $120,000 annual maintenance budget. Galveston County commissioners balked, looked at cheaper solutions, and ultimately did nothing. Or as the Corps had written about earlier warnings that were likewise ignored, the plan was dropped because of the expense and “general public apathy.”

Long derided as the tacky little beach town in Houston’s backyard, Galveston by the summer of 2008 finally seemed to have won some of the respect its business leaders had sought so desperately for so long.

Most of its Victorian houses in the East End and Silk Stocking historical districts, many of them crumbling wrecks as recently as the 1960s, had been handsomely and lovingly restored. When the azaleas, crepe myrtles, and other blooming trees and vines were in full flower, those neighborhoods rivaled New Orleans’ genteel Garden District. Tourists flocked to ogle selected examples on popular Mothers’ Day weekend tours sponsored by the city’s premier social charity, the Galveston Historical Association.

And when these 19th-century places were advertised for sale for $200,000 to $400,000 or more, they still seemed like steals to well-heeled out-of-towners compared, say, with similarly sized period pieces in Houston’s Heights or Fort Worth’s Mistletoe Heights. Increasingly, they were snapped up as second homes by mainlanders. Moreover, the island’s East- and West-End beaches increasingly were festooned with million-dollar-plus, pastel-painted mansions owned by wealthy lawyers, oilmen, and entrepreneurs and others from Houston and farther afield.

These new haunts of the super-rich were celebrated, in the real estate pages of The New York Times and elsewhere last year, as Texas’ version of the Hamptons. Dissidents, including coastal geologists, warned that the entire island was a geo-hazard subject to catastrophic flooding. Others fretted that by surrendering much of its housing stock to largely absentee owners with primary homes elsewhere, the community was losing its middle class and, perhaps, its soul.

“The city government has been subsidizing resort developers through tax increment reinvestment zones, known as TIRZ,” said city councilwoman and attorney Elizabeth Beeton, a strong critic of these practices. “The city has also asked its middle-class residents behind the seawall to subsidize very expensive sewer systems on the west end of the city” beyond the seawall. She complained that the city also issued permits, with terms favorable to builders, for resort developments on the island’s West End. These practices — reflexively backed by Galveston Mayor Lyda Ann Thomas and most of Galveston’s exceptionally parochial city council — have “got to stop,” Beeton argued.

Because there was money to be made and hefty property taxes to be garnered, most of the city’s elected leaders seemed to adopt “caveat emptor” as Galveston’s unofficial motto. Until the bursting national real estate bubble brought things to an abrupt halt earlier this year, the breakneck vacation-housing boom continued apace on the approximately 18 miles of Galveston Island west of the seawall’s end — including bay houses, some with networks of canals that, geologists warned, could effectively split the island in two during storm surges and backwashes. Moreover, the beaches of the West End, even before Ike, were fast eroding, despite various efforts to stem the retreat. Experts recommended withdrawing much of the West End from further development, citing flooding dangers and the prospect that the highway serving the area was expected to be under water within the next 30 years or so.

The city didn’t totally ignore its land-use problems. It commissioned a study by the University of Texas’s Bureau of Economic Geology. Those researchers advised creating buffer zones to shield beach fore-dunes, safeguard new wetlands, and defend a protective central ridge. All these measures were designed to spare Galveston from being broken apart during the next big storm.

However, blinded by the prevailing development-at-any-cost mentality and their woeful ignorance about the environmental processes governing barrier islands, the council whiffed. In May 2007, instead of embracing the suggested land-use curbs, they voted instead to let those innocent new buyers of west island properties read the study if they chose to do so, pay their taxes, and take their chances with Mother Nature.

“If they want to live on the edge and risk losing it all,” City Manager Steve LeBlanc told the Galveston County Daily News last year, “that’s their decision.” Damn the environment! Damn the hurricanes! Full speed ahead!

Through 2007, Galveston’s seawall admirably served its purpose, protecting the city from the worst effects of the major storms that, on average, have come ashore there every 20 years or so since 1900. But the wall also acted to interrupt the usual rollover that is an integral element of a barrier island’s nature.

Because of that blockage and other barriers — most notably the changes in the way the Mississippi and Brazos rivers’ silt load is dropped — the beaches beyond and beneath the Galveston seawall shrank and in some places have entirely disappeared (except for Galveston’s East Beach, which is growing thanks to prevailing northeasterly tides and the jetties’ action in capturing sand escaping from the western part of the island). Satisfying beachfront hoteliers’ and others’ demands for public beaches in front of the seawall requires periodic, expensive, and only temporarily effective, beach re-nourishment projects. Even at its best, the seawall can do only what it was designed to do — protect the city from the gulf’s frontal assaults. But as the French discovered in World War II with their infamous Maginot Line fortifications, designed to protect against German and Italian invasion, there is another possibility: an enemy that simply swarms around the line to attack from the rear.

In 1961, when Galveston’s Ball High School reopened after leviathan Hurricane Carla had crashed into the Texas coast 130 miles south-southwest of Galveston (and on the 61st anniversary of the 1900 Storm), my high school chemistry teacher G.W. Bertschler warned my disbelieving class that Galveston could suffer much, much worse during the May-November hurricane season. Carla’s winds and the tornadoes it spawned had badly torn up the city. Yet Mr. Bertschler — whose original career path had been meteorology — warned that if the eye of a storm as big as Carla’s were to cross the northeast tip of Galveston between the island and the Bolivar Peninsula (rather than following the most common route and making landfall between San Luis Pass at the south/southwestern end of the island and Freeport), we’d be in for very big trouble.

That monster storm’s counterclockwise rotation would sweep a huge and deadly dome of saltwater 20 to 25 feet high or more into Galveston Bay, he explained. Following this storm surge would be a backwash of almost biblical proportions, flooding Galveston from the mainland-facing port forward to the gulf-facing beachfront. Typically, the surge and its backwash are responsible for almost all the deaths in hurricanes. We would “drown like rats,” Mr. Bertschler prophesied.

Fast forward to the second weekend in September 2008: Mr. Bertschler’s scenario was played out in dress-rehearsal fashion, without the massive loss of life but with huge property losses. In its traipse across the Turks and Caicos Islands and then over Cuba, Ike had shrunk from a killer Category 4 to a high Cat 2 storm — and 2s are typically considered pussycats, not major hurricanes. Moreover, it was a 2 with a curiously misshapen eye, and the preoccupation with its anomalous appearance initially may have caused storm watchers to give it insufficient respect.

Ike finally wobbled across Galveston Island during the very early hours of Saturday, Sept. 13, almost exactly where Mr. Bertschler warned that such a storm might hit. By then it sported a mammoth consolidated eye 60 miles wide embracing the entire island, with 110 mph winds and a leviathan wind field circulation encompassing much of the Gulf of Mexico. With it came a dome of water 13 to 14 feet high, built from the waters of the Galveston Ship Channel, Galveston Bay, and Gulf of Mexico. The water invaded and inundated an estimated 80 percent of the island’s 24,000 structures and did extensive damage beyond the island on the Bolivar Peninsula, even knocking out enough electricity lines to effectively paralyze Houston for a few weeks. The storm also did about $350 million in damage to East Texas timber — far below Hurricane Rita’s toll three years ago, but still painful.

Fortunately, Ike defied the predictions, broadcast repeatedly in the days leading up to landfall, that it might strengthen to a Category 3, meaning Galveston would have faced a 20- to 25-foot storm surge. National Weather Service advisories had warned: “Persons not heeding evacuation orders in single-family one- or two-story homes will face certain death.” The surge actually reached 21 feet at a Texas City levee. Because about 20,000 Galvestonians had defied the order and stayed home, a slight westward adjustment in Ike’s course could have turned a disaster in Galveston into a catastrophe.

My cousin Nick, his daughter Catherine, and her husband Tony lived on the eastern end of Galveston in a neighborhood commonly called Fish Village that is popular with employees of UTMB. They were among the thousands of Galvestonians who stayed put despite the “mandatory” evacuation order and dire warnings. But by the early hours of that Saturday morning, they recognized that they’d made a big mistake.

As the first half of the huge storm moved through, the house flooded to a depth of two to three feet, and Catherine began to contemplate a vertical evacuation — at first into the attic and thence, perhaps, onto the roof if they could punch a hole in it. That New Orleans-style escape seemed too bleak to consider, and so, when the eye of the hurricane passed over shortly after 2 a.m., they took advantage of the relative calm to leave their flooded house and set out with their new puppy and an 84-year-old neighbor to wade through waist-deep water to a nearby low-rise condo. There they hunkered down in third-floor inset doorways for the balance of the storm, pelted by 110 mph wind and rain.

At daybreak, when the storm had passed, the neighbor went home, and a police officer gave the other three (plus their puppy) a ride to within 10 blocks of Ball High School, the shelter of last resort in Galveston. Again they waded through deep water to reach the school and its predictably chaotic shelter. On Sunday morning, a bus took them to a shelter in San Antonio. Now my cousin, a retiree, is visiting his eldest daughter near Baltimore. His younger daughter and her spouse are back in Galveston, working and living in a family friend’s beach house.

Why did 40 percent of the city’s population ignore the mayor’s evacuation order, issued 36 hours before Ike’s landfall?

Perhaps it was simply because a Category 2 storm doesn’t sound so bad. A quarter-century earlier, many long-time Galvestonians, including me, had stayed in Galveston for low Category 3 Hurricane Alicia without lasting ill effects. Because my widowed mother refused to leave, she and I and my niece rode out that storm in Mother’s house a few blocks from the beachfront. The two-story frame structure, a Dutch colonial with a pier-and-beam foundation, swayed like a reed much of the night, buffeted by Alicia’s banshee winds, but the house and its occupants came through generally unscathed.

Or perhaps many others, like me, were suffering “evacuation fatigue” this time, having fled over the Labor Day weekend less than two weeks earlier from Hurricane Gustav, which ended up veering into Louisiana and battering Baton Rouge. (Finally I too fled from Ike, heading for Austin 19 hours before Ike made landfall.)

Maybe remaining on the island to shelter in place made sense to those who considered the weather service prediction of a 20- to 25-foot surge to be wildly hysterical. Some surely had no money or no place to go. The troubling thing about evacuating from Galveston or other coastal locations is that you’d better have a plan ready before the storm approaches. Because if you don’t leave before you really know that you need to, you may not be able to get out — you may be stuck on the roads in gridlock traffic, find that rising water has blocked your egress, or, worst of all, get trapped on the freeway during the storm and drown in your car.

A week after Ike’s landfall, I visited Galveston for four hours as a reporter, leaving just ahead of a 6 p.m. curfew. I returned nine days later, when residents were being allowed back onto the island despite the absence of electricity, natural gas, potable water, and most medical services. And in those two visits, I began to comprehend the extent of the blow the island had sustained.

Some homes and businesses were buried for a time beneath 13 feet or more of water, which often was diesel-laced and evil-smelling. The surge crushed or dismantled a number of structures near the water, especially those beyond the seawall and, along it — including the Balinese Room, remnants of which ended up on Seawall Boulevard, and Murdoch’s Pier, which held fast to its pilings but lost much of its walls, its contents disgorged into the water below. Ike also wrecked nearly every business in the Strand Historic District.

Almost every house had the water-stained possessions of a lifetime — furniture, beds, appliances, books, drapes, rugs, books, art, stereos, computers — piled outside along the curb. Every day for weeks the old piles would be hauled off, and new ones would miraculously appear. Then came the water-damaged sheetrock and other building material.

More than a month later, gas, power, and phone service still hasn’t been completely restored, but streets except for Broadway are regularly cleared of debris, many traffic lights are once again functional, and, as with Katrina, residents are dealing with a sometimes feckless Federal Emergency Management Agency. FEMA started off strong, but its bureaucracy has increasingly seemed to aggravate business owners’ and residents’ multiple frustrations in trying to return to normality.

The storm also seriously wounded a major Galveston institution and economic sea anchor. A few days after the storm, word leaked out that the regents of the UT System were leaning on the Medical Branch — the state’s oldest health sciences university — to lay off a quarter of its staff of 12,000 due to heavy and mostly uninsured damage to the 84 buildings on its sprawling campus. UTMB also plays another key role on the island: providing medical care to Galveston’s many poor and uninsured residents. The layoff decision — supposedly (and unbelievably) requested by UT System regents without consulting the state’s political leaders — apparently has been shelved until after this week’s presidential election, but sources say it’s likely to be acted on then.

Beeton is not counting the city out yet: “Our citizens are keeping body and soul together while we have an opportunity to analyze where we are, what we’ve lost, and what our new opportunities may be,” she said.

Rape victims often say that it takes them years to overcome the horror of their experience and regain the equilibrium and sense of security they need to get on with their lives. If the act took place in their homes, they frequently feel that they can no longer live there, and they get out and go elsewhere. Many Galvestonians may feel the same after Hurricane Ike.

Former mayor Barbara Crews said she expects the city’s population — now about 57,000 — to decline by 10,000. That’s quite possible, considering the extent of the damage. In the much smaller coastal community of Pascagoula, Miss., 80 percent of its structures were flooded by Hurricane Katrina’s 20-foot storm surge. In the three years since, town officials said, Pascagoula has lost 10 to 15 percent of its population.

On a Tuesday in mid-October, former presidents George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton stood on the badly eroded shoreline amid the wreckage of a west island subdivision called Bermuda Beach. There, for the benefit of reporters, TV cameras, and newspaper photographers, the former presidents formally launched their Bush-Clinton Coastal Recovery Fund, designed to raise private contributions to aid victims of hurricanes Gustav and Ike. It was a reprise of their efforts in 2004 and 2005 to assist victims of the South Asian tsunami and Hurricane Katrina, but whether it will be as successful during a financial meltdown is problematic. With his arm draped around the shoulders of Mayor Thomas, Clinton said, “I don’t think the American people understand how much [help] you still need here.”

Clinton was certainly right about that — although he seemed unaware of how much of that public ignorance is owing to the actions of the mayor and the federal authorities who hunkered down with her and the media in the fortress-like San Luis Hotel during and long after the storm.

From a friend’s living room in Austin, I watched the continuous TV coverage of the hurricane. To my surprise and annoyance, most of the reporting from Galveston seemed to consist, the morning after landfall and for days thereafter, of repeated scenes of beachfront destruction within easy reach of the San Luis. I saw no footage of the Strand Historical District in the lowest and most flood-prone part of the central city. I saw nothing about the destruction on West Galveston Island (from which reporters were barred) or Bayou Shore Drive (where many homes were demolished) or about the flooding and condemnation of all Galveston’s traditional public housing projects. I heard no broadcasts from the flooded areas in the East End Historical District and Fish Village, or anything about UTMB.

The day after the storm, the mayor forbade all city employees except the city manager to talk with the media. Thomas didn’t seem to want Galveston’s own citizens, much less the media, to see the island in its sad state of dishabille — a decision that made it much harder to generate the sustained public sympathy needed to influence politicians in Austin and Washington to come across with major disaster aid.

Dolph Tillotson, publisher of the Daily News, smelled a rat. In an editorial, he called the mayor’s action “a desperate effort to avoid embarrassment for the Republican administration in charge of FEMA.” Tillotson, whose paper subsequently endorsed U.S. Sen. John McCain for president, noted the coming national election and added: “Nobody wants another Katrina this time.”

Predictably, then, almost as soon as Ike was gone, public attention was diverted from Galveston’s disaster. Without a compelling picture of the city’s destitution before it, the national media seamlessly shifted its focus to the world financial meltdown and presidential election.

Galveston County Engineer Mike Fitzgerald says the levee ring project proposed in the ’70s, which would cost $800 million today, would have spared Galveston 90 percent of the damage it suffered from Ike, including a huge percentage of the $700 million in damage at UTMB. Meanwhile, a levee system constructed in the Galveston County community of Texas City to protect its oil refineries and other industries after they were flooded by Hurricane Carla in 1961 has stood up to every storm since.

The costs of repairs from the major storms that regularly pummel Galveston is increasing. Ike will be the costliest yet, in part because properties on the West End last year were worth a total of $1.6 billion, according to the Galveston County Central Appraisal District — four times the value of all the taxable property behind the seawall. But as Ike’s flooding demonstrated, not even property behind the seawall is safe when a hurricane enters the chute between the northeastern tip of Galveston Island and the Bolivar Peninsula.

Like Hurricane Katrina, Ike’s appalling inundation of Galveston seems a harbinger of catastrophic weather events to come — Mother Nature’s payback for Americans’ profligate production and consumption of heat-trapping greenhouse gases that most scientists agree are at the root of the world-wide climate disruption.

Ten days after the storm, Thomas testified before a disaster-recovery panel of the U.S. Senate, asking that the federal government pump an extraordinary $2.2 billion into rebuilding our stricken city. Lest anyone overlook her patrician roots, she noted that her grandfather, banker and entrepreneur Isaac H. (Ike) Kempner, led the city government after the 1900 Storm.

The mayor said that the lessons from her grandfather and his generation of Galvestonians “form the basis of today’s hurricane recovery.” Exactly what those lessons were she didn’t say.

In her testimony, Thomas described Galveston not as the environmentally fragile barrier island that it is or the rare and quirky end-of-the-road community its denizens treasure but in more commercial and less spiritual terms as “a viable, valuable piece of real estate” — a phrase the city’s plutocrats at the turn of the century or the county commissioners in the 1970s or the city council majority today would understand.

A levee system, however, was not part of the mayor’s wish list.

Tom Curtis, whose journalistic credits include a stint as a reporter and assistant city editor of the now-defunct Fort Worth Press, still lives in Galveston — God knows why.

Email this Article... Email this Article...

|

|