|

|

Keely stays in touch with friends via e-mail from his underground office. Courtesy Bo Keely

Keely stays in touch with friends via e-mail from his underground office. Courtesy Bo Keely

|

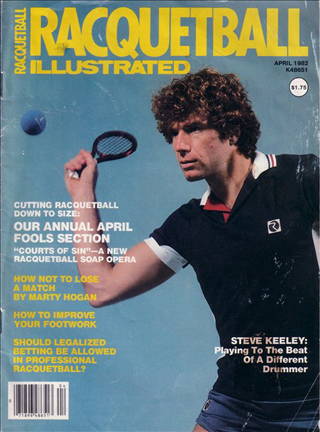

The headline said it: Keely played to a different beat. Courtesy Bo Keely

The headline said it: Keely played to a different beat. Courtesy Bo Keely

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Renaissance on the Rails

“Bo” Keely has advised millionaires, but he’d rather be hopping freights.

By PETER GORMAN

A winter sun was shining, but a chilly wind rushed through the tall grass between an abandoned building and the rail lines of Tower 55, the freight yard beneath the freeways at the southeast corner of downtown Fort Worth.

“The way you scout out a yard for a ride is to go into the yard at night and talk to the brakemen and yard workers,” said Steve “Bo” Keely, a ruggedly handsome, lanky man of 60. “The key points are what time the next train is leaving in your direction, which track number it’s running on, and where the units, engines, head up. Then you ask if there are empties — empty box cars — and whether you need to worry about the bull, the railroad policeman.”

But this time, he said, “I didn’t see any yard workers … and it’s daylight. It might be tough.”

It turned out not to be. We’d parked the pickup next to the west end of a long warehouse and crossed the grassy stretch to the rails without being seen. There was no fencing around the eastern end of the yard, so crossing the tracks to the mile-long string of freight cars was no problem.

Keely began moving up and down the train, pointing at the cars and explaining their uses in staccato bursts: “Flatbed for moving lumber or pipe or sheetrock, curve-sided hopper generally for moving cement or grain, high-walled coal cars, boxcar, cattle car, black oil tanker.”

He pointed out the benefits and liabilities of each. “Flatbed looks good but too easy to get spotted, and it gets too cold at night. Also too easy to fall off.” High-walled coal cars are easy to hide in but difficult to get out of. Boxcars are good, but only if they’re open. He said the railroad companies keep the doors open on empties so that hoboes and tramps riding the rails won’t break into loaded cars.

His personal favorite rides include the “back porch” on curved-side hoppers. It’s a space about 8 by 12 feet at the rear of the car and often comes with a hobo bedroom, a small, mostly enclosed space under the car’s reinforcement where a single person can squeeze in to get out of the rain. He finds one, and we practice getting up and down from the porch. “Never use the front porch,” he said, “because if the train stops suddenly, you’ll be thrown forward, and a lot of men become rail grease that way. If the train stops and you’re on the back porch, the worst that happens is you bang your head. Always have a hat.”

Suddenly a Burlington Northern-Santa Fe engine appeared around the track bend at the far west end of the yard, pulling an eastbound string of cars.

“Climb on the porch and stay low,” he ordered, and he did the same, just moments before the new arrivals rumbled in. Three engines and a dozen mixed cars slid past on the next track before coming to a halt.

“Might have been seen. If so, the yard bull will be here in seconds. I’ll scout.”

Suddenly he was moving like a cat, down off the car and keeping low to the ground, moving in the direction of an empty flatbed that would give him a view of anyone headed our way. “Off the train,” he ordered in a few moments. “There’s a Jeep headed this way. Probably the bull. If it is, head toward the back of the train. He won’t chase us far, if he’s like most bulls.”

Keely dropped to his knees and scanned the landscape from behind one of the steel behemoth’s huge wheels. “He’s turning. Lazy bull. We’re clear.”

He stood and dusted himself off. “Probably a crew change,” he said, assessing the reason for the stop. “It’ll only take a few minutes. Next stop could be eight hours away at the next crew change. Or it might be Dallas. Ready to ride?”

You bet.

Keely turned and began walking away from the engines, scouting a car. There was a curved-side hopper about half a dozen cars down the track on the new train. “If she moves, we’ll take this,” he said.

He’d hardly finished saying that when the air brakes shrieked and the engines began to yank the cars behind them into motion. “I’ll get on here,” he said from 20 yards away. “You catch it as I pass you.”

As the train went slowly by, he said: “Grab the ladder with both hands. Keep both feet on the ground until you’ve got it. Now one foot on the ladder ... now the second ... and you’re on. You’ve just hopped your first moving freight.”

We sat down on the metal grid flooring as the warehouse receded. “I ordered a copy of one of my books for you,” Keely said, out of the blue. “It ought to be at your house in a couple of days.”

Which one?

“The racquetball book I wrote in the ’70s.”

The train began to pick up steam as it passed under I-30, heading east. “We’re committed now,” he said. “No getting off till it stops, which will probably be Dallas but might not be till we hit Texarkana, the next crew-change stop.”

He sat back and smiled, enjoying the sun setting over the Fort.

Hopping freights has been one of the defining themes of Bo Keely’s life for the past 30 years. Some years he rides for a month; others for most of the year. But that’s not what makes him unique. Lots of people ride trains, though not nearly as many as did during the hobo-ing heyday from 1929 through the mid-1950s, when it’s been estimated that more than a million people were on freights at any given time.

What makes Keely unique is that he’s probably the only guy riding the rails who’s been a national paddleball champ, written a best-selling book, and traveled around the world on a millionaire’s check looking for financial indicators among the world’s poor that would make the rich guy even wealthier.

His nickname is short for “hobo,” but Bo calls himself “a boxcar tourist” as opposed to a bona fide hobo who rides the rails from job to job. His life is defined by the sheer unpredictability of it, with the only constant being that he will keep on moving.

People who climb aboard those big metal monsters — sometimes for fun, sometimes for work, sometimes just to get to someplace new — tend to be characters, but Keely takes the theme over the top. He’s a brilliant guy, a world-class athlete who won seven national paddleball championships during the 1970s, a retired veterinarian. He’s also written a half-dozen books on sports, including The Complete Book of Racquetball, which sold 150,000 hardcover copies. (It’s listed under Keeley. He’s since dropped the last ‘e’.) He’s been a school teacher, slept one winter in a coffin, hiked Death Valley, and ridden the rails for weeks on end through Central America, Mexico, and across the USA.

For all that, however, he’s clearly attached by only a few hooks to what most people consider the normal world of jobs, families, stability. He’s rarely had a telephone in the last 30 years, his address is often a rented garage or basement in whatever city he settles in for a few months, and his friends are people he has to travel to visit, rather than talk with over the backyard fence. At nearly every one of life’s crossroads, he’s given up the straight and narrow for the crooked path to adventure.

He chalks it up to his childhood. Born in Schenectady, N.Y., in 1949, his family — which includes a very normal brother — moved regularly as his dad moved up the job ladder from blue to white collar to nuclear engineer. At every whistle stop from coast to coast where they moved, Keely remembers watching guys in patched clothes waving and shouting from boxcars as if they didn’t have a care in the world. “I wondered where they came from and where they were going,” he said. “I thought it must be wonderful to peer out of a freight.”

His father, Gil Keeley, described Bo as a conservative kid. “He was a good kid, played some sports, loved animals. His mother and I visualized him settling down, working with animals, having a family. We sure didn’t see him living the life he’s chosen, but you know, as parents you accept your kids’ choices.”

Keely said that in high school he was a mediocre athlete who wrote a lot and was good at chess. But he blossomed at Michigan State University, where he picked up his first paddle in 1967. He spent hours practicing on the intramural courts and in 1969 became the university’s intramural paddleball and handball champ.

In 1970, he hitchhiked the 900 miles to Fargo, N.D., for the national paddleball championships. “I had no money,” he said, “so that was the only way I was going to get there.” He didn’t win but played well and was beaten by a former national champion.

The following year he only had to hitch 50 miles to Flint for the national championships. “Three days later the press headline read ‘David Slays Three Goliaths’ after I’d beaten the three previous national champions to become the champ myself,” he said. Later that year he was runner-up in the first National Racquetball Singles Invitational in San Diego.

Like many wall-ball sport enthusiasts, Keely plays both paddleball (played with a solid paddle) and racquetball (played with a short-handled stringed racquet) as well as handball and squash. Keely prefers paddleball, which utilizes a ball with a pinhole to slow it down, making it more of a strategic game compared to the speed and fury of racquetball. Through the years, he made more money at racquetball but was better at paddleball.

By 1973 he’d passed the Michigan veterinary exams and moved to San Diego, a paddle- and racquetball mecca, where his roommates included luminaries in the sport such as Marty Hogan and Charlie Brumfield. He still intended to practice as a vet, however, and passed the California veterinary exam on his first try. But California bureaucracy took six months to approve his license to practice, and during that time he won his second national singles paddleball championship. The lure of becoming a professional athlete was too much to resist.

Having made that decision, Keely threw himself into training, running six miles a day, biking 30 miles, doing an hour of weight training, and spending a minimum of two hours daily on the court, a regimen he kept up for five years. The work paid off quickly: He was sponsored by both the number-one racquet maker at the time, Leech Industries, and by Converse shoes, which paid him $1,000 a year despite his insistence that he be allowed to wear two different colored sneakers on the court during tournaments.

Shoes weren’t Keely’s only eccentricity. Already the road was calling: In 1973 he rode his bike 2,400 miles, from San Diego to Michigan, in 30 days to see his family — with a three-day layover in St. Louis for the national racquetball championships. He didn’t place that year, but in 1974 he was national runner-up, won his third national singles title in paddleball, and also took the Canadian national racquetball title. He placed second in the inaugural International Racquetball Association’s Pro-Tour stop in Denver for his first prize money.

Over the next several years he won hundreds of tournaments and several more paddleball national titles and wrote his best-selling instructional book, all of which earned him cover stories in several major sports magazines. Sports Illustrated called him a co-founder of modern racquetball. And while prize money rarely topped $2,000 per tournament win, he earned enough money to invest in several rental properties in Michigan.

Marty Hogan, racquetball’s first millionaire player, told Fort Worth Weekly that Keely was “unquestionably the best paddleball player of all time,” with a unique blend of “brilliance and simplicity that made him the most popular player in the early days of racquetball.”

Keely left active competition in the late 1970s. “I loved paddleball but never felt that way about racquetball,” he said. “I always thought it was too fast to be called a sport. I played for the money, travel, contacts, and the girls. But I left because it became corrupt. Not just throwing matches, but cheating, draw fixing, ball substitutes, unscrupulous officials, politics between manufacturers, kickbacks — the same things that go on in other sports where money replaces pride as the goal.”

He didn’t drop the sport entirely, however. He continued giving clinics, making guest appearances at tournaments, and hustling games with overconfident players. His most memorable match? A 1980 exhibition in which he beat the runner-up for the Ms. World title, using a high-heeled shoe instead of a racquet. The prize? A date with her.

While the clinics were fun and earned him a living, Keely itched for something more adventurous. He found it in freight-hopping.

He grabbed his first ride out of Salt Lake City after a racquetball camp he ran there. “I’d read the book The Freight Hopper’s Manual for North America by Daniel Leen while I was there. Then I went down and talked with a railroad yard worker.” He came back the next day “with a backpack and the Converse All-Stars that had helped me win championships for years, just hoping not to get cut in half or mugged along the rails.”

Spotting an open, rolling boxcar, he sprang off the grit and into a new life. The mile-long mixed-car freight, pulled by five locomotives, took Keely across the Great Salt Lake causeway, through the scorching Great Basin desert into California and up through the snow-covered tunnels and mountainsides of the fabled Feather River Canyon, considered to be one of the most spectacular sections of rail in the country.

For Keely, it was a wonderful initiation. Along the way he was joined by two other hoboes. “I sat at one end of the boxcar in Central California’s orange orchards, and at the other end hunkered two staring, crusty hobos with tattoos,” he said. “There I sat with a block of cheese, bread, and a knife in my pack. I didn’t take it out until my stomach insisted, and when I did I yelled ‘Are you hungry?’ to the two men, over the din of the car rattling on the track. ‘A tramp’s always hungry!’ one roared back.”

Keely walked up to them, handed over everything and waited. “They made three equal sandwiches with the cheese that was to have lasted another day, and we ate wordlessly.”

But he was well-rewarded for his kindness. They taught him not to sit at the front end of a boxcar where an emergency stop would smash his head into the wall, not to dangle his legs out of the open car door because a railroad sign might take them off. When the freight stopped, one of the men hopped down to gather oranges for dessert while the other went to “gooseberry socks — steal socks from a clothesline — to keep our feet warm.”

By the time the freight pulled into a San Francisco yard two days after leaving Salt Lake City, Keely was hooked. Over the next few years he rode the rails from sports clinic to sports clinic by choice. He had money in the bank, in part from the rental properties, but simply preferred the adventure.

And what did people think when he showed up for a clinic or exhibition covered in rail dirt? “It wasn’t anything out of the norm for me to show up dirty-faced with rail grit and walk onto the fishbowl exhibition court to teach or play,” he said “That was part of my persona, it was me, and it was part of the show.”

And after he gave up the clinics, he kept riding. During the last 28 years, he’s caught hundreds of freights and logged tens of thousands of miles. He marks his most memorable as his annual Christmas swings along the old Southern Pacific route from Los Angeles to visit his family when they lived in Grand Prairie — he always wore red stockings for the occasion — and his worst as the northernmost cross-country trip from Seattle to Minneapolis he took in wintertime some years ago.

Describing that trip, Keely switches to his storyteller mode, seeming to look inside his head for memories and then talking as if he were reading from a book. “It was 1985. I was wrapped up in cardboard and shivering, with spaghetti sauce frozen in my beard as snow swirled into the boxcar door. I landed in Michigan, bought a coffin from a fellow who happened to be selling one, lined it with electric blankets, rented a basement, and slept in that coffin for two days, trying to figure out what to do. Then I rose from the dead and walked to the sociology department at Lansing Community College and suggested to the department head that he let me teach a hobo course.”

Bo said the dean, Dr. Ben Heater, blanched at the suggestion but asked to hear more. Bo gave his credentials: his work history, as well as his hobo history, which included attending five national hobo conventions in Britt, Iowa, and owning probably the world’s largest hobo library. “I also told him it was mid-winter, and I needed to make a stake for the spring. I wasn’t broke, but I still needed the work.”

“It was a wonderful idea,” Heater recalled recently. “So I let him set up a seminar — we had a program called Lifetime Studies Seminars in the sociology department, and this was one of those.”

Heater went for it on the condition that Bo sign up a minimum of eight students. To do that Keely tacked up posters on every building and telephone pole in walking distance of the college. The posters showed a Weary Willie, a caricature of Emmett Kelly’s famous hobo clown, with a beer in hand, under a banner that read: “Hobo Class — I Want You.”

An attorney signed up, followed by an anthropologist, an electrician, a historian. In all 36 people enrolled.

He modeled his class after the Hobo College in Chicago run by Dr. Ben Reitman in the 1920s. Reitman offered topics ranging from self-image improvement to practical advice on taking soap from public bathrooms as ammo against the “gray soldiers” — lice. He taught English composition, philosophy, public speaking, and the law. The intent was that after just one week at the college, a down-at-the-heels walk-on could graduate with a job, a place to stay, clean clothes, a better vocabulary, and an association of peers.

When time came for his first class, Keely was a nervous wreck. He tried to picture Reitman striding into his college. So he drew himself up and strode into the room that he’d decorated with railroad maps, rail company flags, early Sally — Salvation Army — posters, and a hundred-book hobo library. A cassette player blared out the song “Wabash Cannonball.”

He turned down the music and started talking. “I’ve traveled the world and hopped about 300 freights in this country,” he told his crowd. “I’ve dined in some of the finest restaurants in the land and eaten on hobo jungle floors. This perspective, I believe, qualifies me as your instructor to talk about hobo life in America.”

Then, he said, “I shut my mouth, shrank into my overalls, and waited for the class reaction. They thundered applause!”

Over the course of the semester, Keely brought in speakers that included a Michigan Supreme Court judge, a professor to teach about hobo economics, a minister to talk about tramp religion, and an anthropologist who traced hobo history back to the Civil War.

“And he did much more than entertain,” said Heater. “He’d take his students around Lansing and ask them to imagine they’d no place to stay and no money, then challenge them on where they’d eat or sleep. Which got them interested in the homeless issue. He showed them the soup kitchens and the flop houses. What he did, finally, was give them a perspective on the issues of poverty. It was a genuine sociological awakening for a lot of his students.”

Not everyone saw it that way. “There was some grumbling from some alumni that we were teaching students how to be street people,” said Heater, “but that wasn’t the case at all. And then someone from the railroad called to say we were teaching people how to jump trains and how that was illegal. Fortunately, Keely happened to be in the room when that call came, and he took the phone and invited the fellow to come talk. And that fellow wound up giving the class the highest praise you can imagine.”

It wasn’t enough. Public opposition and threats from several alumni to withdraw financial backing from the school forced Heater’s hand. “He told me, ‘Just as easily as your class door was opened by public interest, it was shut by public pressure,’ ” Keely recalled. “So I finished teaching the semester, and that was that. I saw the closing as just another curve in life. I’d made a spring stake. I sold the coffin for a little on the side and hit the road.”

For most of the last few decades, Keely hasn’t ridden freights and eaten in soup kitchens strictly out of financial necessity. On the other hand, he couldn’t have afforded to spend nearly so much time on the road if he’d routinely eaten at cafés and stayed in even low-rent motels. Living cheap — and partially on others’ largesse — made possible the life he wanted. There was a time or two, however, when he was as broke as the most down-and-out tramp.

He tells with relish about coming into Minneapolis in the early 1980s without even a pair of shoes.

“A hobo’s most important possession is his boots. A smart ’bo sleeps with them on or uses them as a pillow. I didn’t one time, and someone either swiped them, or they went bouncing out of the car. In any event, I arrived in Minneapolis with no money — this was in the time before ATMs, remember — and no boots,” he said. “I ended up walking into a jail to ask the officer in charge for a bed for the night.” The jailer took one look at Keely, shoeless and tattered, and hustled him off to the local psychiatric ward.

“It’s common for princes of the road to check into ‘psych’ wards for a three-day observation stint and a chance to freshen up,” he said. “There are free drugs, girls to look at, a television … . If you refuse their drugs for three days it proves your sanity, and the head shrink springs you.” Despite all those amenities, though, “it was a desperate week,” he recalled.

According to his dad, that might have been the only time Bo ever called him asking for a few bucks to get him through.

Keely admits the situation was of his own making. “I didn’t know about missions, clothes vouchers, and Sallies at that time. I was still new and had heard that the psych ward was a good place to be.”

It wasn’t, but the people he met there made him want to learn more about mental illness. A couple of years later, when he was teaching his hobo class, he took a few courses and got certified as a psychiatric hospital technician. The certificate gave him access to jobs in psychiatric hospitals, wards, and emergency rooms. He talked to troubled people who called looking for help, he emptied bed pans, he scrubbed floors. And he worked on his own theory about how the mind works — that maybe mentally ill people had a couple of puzzle pieces that the rest of us didn’t. “But after a year doing that I was a basket case,” he said.

He’s taken plenty of other jobs to support his “rail” habit. He’s landscaped in Oregon, collected cans in Salt Lake, chopped wood in Montana, and volunteered on soup lines. “But that’s absolutely nothing compared to a real working hobo who glides along the rails from job to job,” he said. “The smart workers carry their pay stubs with them to make it easier to get the next job. I met one guy in North Dakota who had a shoebox full of hundreds of pay stubs from temp jobs around the country.”

Getting stuck in a town without a cent or getting ripped off for your boots can make you smarter the next time around, he figures. Keely can rattle off the best town for soup kitchens (Minneapolis, where there are 12), best city for hoboes (Salt Lake City because of the Mormon generosity), and best dumpster dives without hesitating. He can tell you where to find the best motels for cleaning up after a cross-country ride (he prefers the mission showers for shorter rides) and has a standing invitation to some of the nation’s best hobo jungles — seasonal hobo camps situated near freight jump-off points and in the vicinity of a mission and a “slave market” (day-labor center). He’s learned to keep up with friends on the rails by scratching his name with a date and a directional arrow on the old water towers that most yards still have, left over from the steam locomotive days that ended in the ’50s.

“You’d be surprised what you can learn in soup kitchen lines,” he said. “For my money, the people that make up those lines are always interesting. They include the truly needy who are thrown out of work during a recession, single moms with kids on leashes, street-smart ex-cons, drug zombies, illegal aliens, and volunteers donating their time. These are people who have been at risk, understand consequence, and still must feed themselves. What can I learn from someone who has never been at risk or toed the line to consequence? The greatest life lessons are found in the food lines, and anyone can go eat there for the experience.”

One thing Keely didn’t expect was to be able to glean enough information about the economy from the rails and missions to be able to go to work for Victor Niederhoffer, the flamboyant speculator who made his mark in the 1980s and ’90s. It might have been one of the strangest pairings in financial history.

The two had met at a sports exhibition in the mid-1970s. Bo was the paddleball champ, and Niederhoffer had been the world champion of squash. There was an instant affinity when each saw that the other wore two different colored sneakers. They kept up a periodic correspondence, and whenever Keely passed through the New York area, he’d stop off at Niederhoffer’s Connecticut home for a while.

On one such visit in the mid-1990s, Keely suggested that Niederhoffer might be able to use intelligence gleaned from the freight-hopping milieu to make predictions about the overall economy and, therefore, about where to invest. Niederhoffer, a partner of George Soros, was acknowledged as an investment genius, providing annual returns of 30 percent and more for his clients. But he was also an eccentric.

“There are a million indicators of how the economy is going,” said Keely. “The number of freight cars trains are hauling tells you whether things are getting better or worse; the number of auto-carrying cars and the sticker prices of those cars tell where auto stocks are headed.” The volume of popcorn sold at movie theaters near skid rows indicates whether panhandlers are doing well or poorly. If a mission starts serving more beef with the potatoes, it indicates that people are donating more food, which means they are confident in the economy. If cigarette butts in mission areas are smoked down to the filter it’s an indication that it’s difficult to bum cigarettes from people, meaning money is tight.

In his best-selling 1997 book, The Education of a Speculator, Niederhoffer notes, “The size of cigarette butts on the ground is directly proportional to the health of the economy … I recently made millions by applying this theory in Brazil. My agents there noted an increasing prevalence of long butts on the ground, and I rushed in to buy Brazilian stocks.”

In a recent phone interview, Niederhoffer described Keely as “one of the most creative people I’ve ever met. He’s got a very scientific mind, and he generated many different hypotheses about market relations. … And I made some good money utilizing some of them. I also lost some where I overextended when I shouldn’t have.”

On the ball court, he said, Bo had “the most liquid backhand I’ve ever seen.” As a person, “he leaves people better off after he’s been with them. … [H]e has a generosity of spirit.”

Keely and Niederhoffer joined forces on other projects, including one in the mid-’90s in which Niederhoffer sent Keely around the world to seed capitalism. Keely’s job during the six-month, 20-country tour was to identify potential entrepreneurs who were just a couple of thousand dollars away from their dream. There were fruit sellers who needed carts, hairdressers who needed equipment, and dozens of others. When Keely came back, he and Niederhoffer went over the list. Keely was to return and deliver the seed money to those with the most potential on the condition that, on a subsequent visit, they would return 15 percent of their profits to him. But on the first day of the delivery trip, two thugs robbed him of the cash, and the project died.

There may be other such collaborations in the future. Niederhoffer is probably as close to Keely as anyone is going to get. His traveling lifestyle doesn’t engender close friendships. He’s had a number of girlfriends but never wanted to marry. He simply prefers short periods of intense interaction over long-term stability.

The most stable segment of Keely’s adult life has probably been the last decade. After a trip up the Amazon in Peru that left him nearly dead from malaria and insect bites, he bought a 10-acre parcel in Sand Valley, Calif., a stretch of desert on the Mexican border next to a bombing range. There he made an office out of a camper he buried below ground, to keep the room cool enough for his computer, and installed a couple of truck trailers that he has made into his home. A handful of other homes are scattered in the valley; like Bo, the residents value their privacy. “We’re all good neighbors because while we help each other out in time of need, we don’t pester each other,” he said.

To support himself, he spent several years working as a substitute teacher at the high school in Blythe, Calif., about 50 miles away. In 2003 he spent six months on a Racquetball Pro-Legends tour, being paid handsomely while flying around the country in a private jet.

He continued to ride the rails but also took to long hikes. He said he’s done 600 miles in the Baja Peninsula, where an overabundance of rattlesnakes made him cut the trip short. He hiked in the Rockies from Denver to Durango and the Florida Trail from the Everglades to Georgia.

What freight-hopping he did during those years frequently involved a project he’d started called the Executive Hobo Trips, in which generally well-to-do men and women pay him to take them out on the rails for a few days, sometimes a week or two.

“From a boxcar, you see America through the back yard,” he said. “The tracks course neighborhoods past their back fences with their clotheslines, their fruit trees, jailed barking dogs, children running and waving.” In the city, it’s the same thing. The tracks usually stream through the old parts of town — the crumbling warehouse district, junkyards, turn-of-the-century factories, skid rows, historic old downtowns — and then blast out to the next town.

The guests come back having seen the world from a different perspective. “They’ve eaten with bums, they’ve been chased by yard bulls. They saw the sun rising from a gondola or box car, maybe had a meal or two in a hobo jungle alongside the tracks and had to pitch in for the beer. That’s something most people have never done, but once you have, well, like me, you’re hooked.”

The first “executive hobo” Bo took out was Doug Casey, a financier and author of several books on investing. “What I remember from my two three-day rides with Bo is the total freedom I felt,” he said. “You’re unattached, and all you need or want are the things you carry with you. You see things from freight trains and rail yards that you won’t see any other way. To tell you the truth, for my money, eating at the mission and sleeping on a siding is a lot more fun and about 10 times more interesting than any five-star hotel on the planet.”

Keely left substitute teaching two years ago and has been car camping in the Southwest most of the time since then — in between long hikes, a six-month rail-and-bus stint in Mexico, and freight-hopping to see friends in the States. And even when he visits friends, he likes to grab a train just for the heck of it.

Our freight heading east out of Fort Worth was that sort of jaunt. The ride might have lasted 20 minutes or 10 hours. As it was, the train ambled past Bedford and Euless and wound up pulling onto a siding just west of Grand Prairie just at nightfall so that a passenger train, which has priority on the rails, could pass.

“On or off?” he asked. “We probably only have a moment to decide.”

“Well, I’m late for making dinner, but I could still get there in time to make the kids breakfast and get them off to school,” I told him.

With that Keely swung himself onto the ladder and down to the tracks, and I followed.

His next order of business was to find two track spikes — for protection, he said. “There might be dogs, bums, thieves … .”

He began the long walk down the tracks back to Fort Worth in the dark, past backyards where dogs barked wildly as the crushed rock of the rail bed crunched under our feet. The tracks themselves were littered with the carcasses of dogs, cats, and raccoons in varying states of decomposition.

How long does he think he can keep freight-hopping?

“Rail riding is an old man’s game,” he said. You ‘catchout’ with your wit, hold down the car with your tail” — meaning you use your brain, not brawn, to find the best train to hop and then sit down and ride. “The keys are not to be drunk, to get in the boxcar before it moves, and get off after it stops moving. The guys who break those rules are called Pegleg or Stumpy or One-Arm. Or worse, they’re left like these animals. For me, I’ll be riding as long as I can climb a ladder.”

Would he pick a different path if he had to do it all over again?

“No,” he said. “This is who I am. Put me in a maze with food — wealth or what have you — on one trail and adventure on the other, I’ll pick adventure every time.”

Email this Article...

Email this Article...