State Rep. Lon Burnam, far right, takes part in a citizen meeting at Botanic Gardens on the parkway controversy.

State Rep. Lon Burnam, far right, takes part in a citizen meeting at Botanic Gardens on the parkway controversy.

|

The proposal for this four-lane road through Trinity Park is headed back to the drawing board.

The proposal for this four-lane road through Trinity Park is headed back to the drawing board.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Drawing a Line at Trinity Park

A controversial road plan may have run into a long-term detour thanks to citizen opposition.

By DAN MCGRAW

After years of lying dormant in the city’s master plan, the idea for a four-lane highway cutting through the western edge of Trinity Park made it to a Fort Worth City Council work session on Tuesday — and promptly got run over.

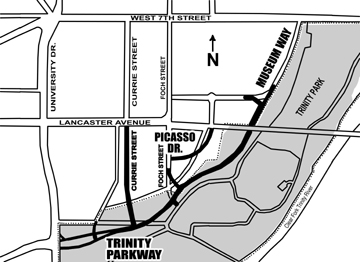

The proposal for a “Trinity Parkway” to link West Seventh Street and University Drive — and the idea that it was justified by the need to alleviate Westside traffic problems — caused a level of anger among many citizens not seen in a while.

Councilwoman Kathleen Hicks called the citizens’ response “mass hysteria on something a long way off.” But the reaction caused the council to backtrack on the parkway plan. After receiving thousands of angry e-mails and letters about taking more than six acres of Trinity Park for the $3 million highway, many city council members want to go “back to the drawing board and begin anew,” councilwoman Wendy Davis said.

Mayor Mike Moncrief agreed. The whole council, he said, agreed that the city needs to take a new look at the issue.

The parkway plan was based on a consultant’s study that predicted traffic patterns in 2025. But the study’s conclusions were that traffic on major roadways in the area will change only marginally, whether the parkway is built or not. And the conclusion that 28,000 cars a day would be using the parkway 20 years from now has environmentalists and old-time conservatives wondering what city the study was looking at. Those wanting to protect the park contend that the Trinity Parkway plan is based upon the needs of big real estate developers and little else.

City staff presented traffic statistics and the preferred route of the parkway at the Jan. 10 work session. But council members knew how hot this issue had become, and many spoke up after the presentation about the need for citizen involvement and the value of greenspace. No action is scheduled on the matter, but between 200 and 300 people showed up Tuesday night just to speak in the citizen comment section of the council meeting.

Opponents of the plan want Fort Worth to change its municipal charter to allow citizens a vote on any future proposal to take city parkland for highways. Timing is crucial — the main reason that citizens packed city hall this week to voice their opinions. If the charter amendment doesn’t get on the May ballot this year, it will be at least two years before the issue can be put before voters, and many protesting the parkway plan think that would be too late.

“The city doesn’t want to hear this, but what they are doing is raping Trinity Park,” said Fort Worth State Rep. Lon Burnam, who has been leading the opposition to the plan. “They are basically concluding that the parkland is better used if they can make a profit on it. But the road is not needed, and the only ones benefiting are the real estate developers. It is sad that we have to sacrifice our scarce parkland for that.”

In fact, real estate development interests — both public and private — apparently led to the proposal being added to the street plan originally. In 1990, when the Fort Worth Stock Show began planning for a new rodeo arena near Harley and Montgomery streets, there was some thinking that a more direct route to downtown was needed for the new arena. According to several real estate developers, the Bass family development group and stock show interests pushed for the parkway to be included as an option in the city’s Master Thoroughfare Plan (MTP).

The original Trinity Parkway plan called for the new road to be built mostly west of the park, west of the rail line that runs on the border of the park, and to use only a small amount of parkland in the process. The idea sat there in the pages of the MTP for almost 10 years without being considered one way or another.

But in 2002, the South of Seventh (So7) development, created by a group headed by Ken Hughes of Dallas, began taking off. A mix of townhouses, retail, and a hotel bordering the park at West Seventh, So7 was supposed to include a roadway from the west linking the south side of the property to the museums of the cultural district. But the plan fell apart when new developers on nearby Foch Street decided they didn’t want to sell the property that would have allowed So7 to cut their “Museum Way” road through.

As a result, the So7 group found itself with only one path in and out of their development, via Seventh Street. And as the Montgomery Plaza redevelopment began to add traffic on Seventh and Acme Brick began considering redevelopment of its corporate headquarters at Currie Street and Seventh into housing as well, the city hired local engineering firm Kimley-Horn & Associates to study the pros and cons of building the parkway.

The resulting proposal is for a rather startling roller-coaster ride for motorists, with a 100-foot-wide divided highway running over levees and railroad tracks, under the Lancaster Street bridge, and at some point going above some of the forested areas of the western edge of Trinity Park. The plan would also extend Currie Street through the parking lot at Farrington Field and into the western part of the parkway.

The consultants were asked to study what effect the new developments would have on traffic on the near West Side, particularly the crowded intersection of Camp Bowie Boulevard, Seventh, and University Drive. Kimley-Horn came to the conclusion that “most of the major arterial facilities” within the study area would be at or near capacity by 2025 — whether the parkway was built or not.

Projecting the amount of traffic with or without the parkway, the consultants came to some rather odd conclusions. They estimated that West Seventh would carry about 29,000 cars each day with the “Trinity Parkway” in 2025, and 30,500 without. University Drive would handle about 38,800 cars if the parkway were built, and 40,500 if it was not. Not a big difference, some say.

Kimley-Horn did not do any projections as to what effect increased light rail or other mass transit services might have in the area. Brian Shamburger, an engineer with Kimley-Horn who worked on the study, said the similar numbers under the “build” or “no-build” scenarios are due to the assumption that the increased traffic in the area would go through the park in any case.

And that is where the numbers became a bit stranger. The consultants’ report said the existing two-lane Trinity Park roads that weave their way from Seventh to University now are used by about 1,500 cars a day. In 2025, the study concluded, the daily traffic on the little roads would increase to 12,600 vehicles if the parkway wasn’t built. With the parkway, a projected 28,200 cars would run through the park, but on the new highway.

Shamburger said he would have to take another look at the study to be able to explain why the traffic in the park was projected to increase by more than 700 percent between now and 2025 without the parkway. He hadn’t responded to Fort Worth Weekly by press time. But opponents of the parkway say the study is flawed in many ways.

“People don’t use that road as a shortcut now, and I don’t know who on earth would use that road as a shortcut in the future,” said Glenn Ford, conservation chairman of the Greater Fort Worth Sierra Club. “There are ways to get around the crowded intersection now, so saying this parkway is going to solve traffic problems is just absurd.”

Neither the So7 nor Event Facilities Fort Worth, Inc. — the development team spearheading the new arena and other developments near Harley Street — returned phone calls. Mark Hill, who oversees real estate development for Acme Brick, declined to comment on the parkway plan.

Davis said at the work session that real estate developers have had nothing to do with the planning of the parkway. But “new solutions have to be looked at because of the concerns of the community,” Davis said. “There is no formal plan to build the road at this time, but maybe we need to go back to the drawing board and begin anew, looking for other options.”

Even though they may have won the first battle, opponents of the parkway are still pushing for a long-term solution. The League of Women Voters, the local Sierra Club, the North Texas Chapter of the Texas Campaign for the Environment — as well as many long-time residents who are not lefty environmentalists — want to let voters decide whether park land can be used for highways.

In order to get the charter measure onto the local May ballot, the council must approve it by the end of this month.

“Parks are too damn hard to get, and we need a plan in place where the citizens can decide if they want to convert this space to something like highway construction,” said Jay Fersing, a retired manufacturing company owner who served on the Fort Worth Parks Board in the 1970s. “There shouldn’t be major highways through any of our parks, especially Trinity Park.”

Burnam said the issue is clear. “People in Fort Worth have a history with this park,” he said. “The land was donated to the city more than 100 years ago, and there are trees there that are older than the city charter. I went to that park to play as a pre-schooler. I got married in Trinity Park.”

“There are other ways to solve predicted traffic problems 20 years down the line than paving over our parkland,” he continued. “It is obvious that all the options haven’t been looked at here. What is being done is driven by the developers, to make their property easier to get to and more valuable. Creating roads like that is fine. But don’t take our parks to do it.”

Email this Article...

Email this Article...