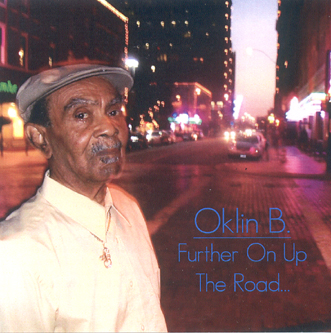

The cover of a c.d. you likely won’t be seeing soon — if ever.

The cover of a c.d. you likely won’t be seeing soon — if ever.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Hot-Blooded

The accusations fly over

what should have been a widely heard c.d. by a local blues legend.

By JEFF PRINCE

The old man’s words could double as lyrics to the blues he sings so well. “When somebody breaks your trust, it makes you feel kind of bad,” said longtime Fort Worth singer Oklin Bloodworth. The sentence was spoken softly on a recent afternoon and aimed at fledgling record producer Manuel Castañeda III.

Castañeda “said, ‘It’s all about the money,’” Bloodworth recalled. “That’s enough to make you want to do something bad. I’ve been praying all day, every day.”

Bloodworth, 78, feels Castañeda exploited him after recording Oklin B. — Further On Up The Road, the singer’s first album. Castañeda disputes the accusations. Strained feelings and a remarkably good c.d. that has been shelved are the result.

Bloodworth’s smooth delivery, dapper look, and gentle nature have entertained crowds at area clubs such as J&J’s Blues Bar and the Black Dog Tavern for years. People are surprised to learn that Bloodworth had never been recorded, especially in this era when everyone with a throat and a dream has his own discography and web site. “Oklin has a deep, rich voice, and a smooth, professional, classy style that is rarely heard or seen these days,” Southwest Blues magazine wrote in 1998. “That he remains unrecorded is a sad commentary on the state of the music industry today. Only in a music-rich area like Fort Worth or Dallas could such a talent perform, week after week, ... ignored by all but a few.”

Two years ago, Castañeda decided to change that. An accomplished keyboardist and sax player, Castañeda had known Bloodworth for more than a decade and played behind him at various venues. Bloodworth’s studio experience was limited, and Castañeda had never produced a record, let alone the handiwork of a singer as talented as Bloodworth, but they went to work. After choosing a mix of blues, jazz, and pop standards — such as “Night and Day,” “I Got It Bad,” and “April in Paris” — the men began recording at Brown Line Studio, owned by the Saenz family of Latin Express. Castañeda used a simple method to capture vocals — he played keyboards while Bloodworth sang. Later, the full backup music was provided by a murderer’s row of local talent, including Buddy Whittington, Dave Milsap, James Hinkle, and Keith Wingate on guitars, Robert Cadwallader on organ, Saenz family members on horns, and numerous other musicians.

The inexperience of the project’s two leaders bit them both. That there is a project at all is amazing, considering that Bloodworth’s original vocal tracks, along with licks from guitarist Hinkle and others, were lost in a computer crash. Everything had to be re-recorded.

The soulful recordings give a sensuous feel to Oklin B., and the song selection puts the singer firmly in his element as a song stylist. In the liner notes, Castañeda calls Bloodworth “a talent too great to describe” and “just a great human being.”

Months later, Castañeda is sad to know that his friend is characterizing him as a shyster. They barely discussed financial arrangements until the project was near completion. Bloodworth expected a 50-50 partnership. Castañeda offered him 20 percent.

“I’m not selling no records for 20 percent, and he gets 80 percent,” Bloodworth said. “That’s my picture on the front and my name.”

Castañeda was floored. He had wanted to give his friend some overdue recognition, spent “countless hours” — about 250, according to his estimations — producing the album, and doled out about $1,500 in expenses. “It’s blown up in my face because he hasn’t put a dime into it,” Castañeda said. “He hasn’t put any effort into it other than doing his vocal tracks. What’s bothering me is that he’s going around telling people that I screwed him. You can talk to anybody else, and they’ll tell you that he is not getting screwed and 80-20 is not a bad deal when you don’t have to put a dime up.”

Bloodworth said he was willing to pay half the expenses but that Castañeda didn’t provide an accounting statement.

Before the relationship fizzled, they discussed printing 200 c.d.’s with a retail price of $10 each. Selling homegrown c.d.’s can be difficult, especially for artists such as Bloodworth who don’t tour. If all 200 were sold, an 80-20 split meant Castañeda would have earned $1,600 and Bloodworth $400. After expenses, Castañeda would show a $100 profit on those hundreds of hours of labor. Bloodworth would have earned $400 for about six hours of studio work.

Leo Saenz, who still considers Bloodworth a friend, said the singer is out of line.

“I wish Oklin would understand that Manuel was trying to do something good for him,” he said. “What hurts me is that Manuel has been tagged as the bad guy.”

Allegations of greed more accurately fall at Bloodworth’s feet, Saenz said. “I don’t think he understands the full amount of hours and manpower and money that was invested,” he said. “Manuel paid a lot of the guys out of his pocket. I was there, and I saw it.”

On the slight chance that the album attracted widespread recognition and turned into a hot seller, Castañeda would stand to earn the bulk of the profits. Few expected that to happen, and that development is now unlikely. Castañeda pulled the plug. Of the 100 c.d.’s that were printed before the fallout, Castañeda had sold 40 and given 30 to Bloodworth. The rest will sit. “I’m just canceling the whole project,” Castañeda said. “It was supposed to be a fun project, and here I am trying to argue with him about money.”

Upset by the accusations, Castañeda is considering replacing the vocals, printing a new cover, and selling the project under a different name. And Bloodworth will go back to being a singer without an album to sell, a beloved man to most folks but one whose star has been slightly tarnished among a few music insiders.

Castañeda “deserves a portion of it,” Bloodworth said. “He was the one with the idea of recording it. But I was the one doing the work — that was my soul. I told him all you have to do is itemize the [expense] account, and I’ll pay half. He’s just running a game. He conned me into singing the songs just to sell me.”

Email this Article...

Email this Article...