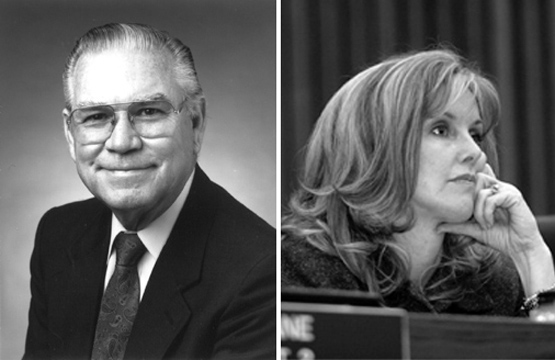

Joe Epps and Becky Haskin lead the Woodhaven charge.

Joe Epps and Becky Haskin lead the Woodhaven charge.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Woodhaven Flame Ups

Some folks say they were misled about the \r\nEastside ’hood.

By JEFF PRINCE

Chuck Silcox was livid after a recent tour of the Woodhaven neighborhood in east Fort Worth. The city council member has often heard from city staff and council colleague Becky Haskin about the ugly apartments, spiraling crime, and general decay in an area near the Woodhaven Country Club, where Haskin lives in T. Cullen Davis’ former home.

Using alleged slum-like conditions at some of those apartments as justification, the city in 2004 filed nuisance abatement lawsuits against two of the complexes, had to defend itself against a countersuit, spent $236,000 on a plan to gentrify the neighborhood (including tearing down several apartment complexes), and, most recently, turned its back on the apartments’ offers to help Hurricane Katrina evacuees.

Silcox no longer buys the hype. Conversations with apartment managers, tenants, evacuees, and police officers who patrol Woodhaven made him realize the propaganda didn’t jibe with reality. He points an accusing finger directly at Haskin.

“Most of the information coming out of my colleague on the East Side, I don’t find it being true,” he said. “The crime rate is no greater than anyplace else that has apartments. The problem is, there are certain people in the Woodhaven area who want the apartments torn down because they want to come in and do some development to make a profit.”

Some residents complain that thinly veiled double fakes by this neighborhood’s movers and shakers are nothing new. For instance, Haskin and the nonprofit Woodhaven Community Development group recently helped a gas drilling company enlist residents for gas leases.

Many residents said they were told by development group leaders that the Four Sevens Oil Co. promised the group up to $90,000 in return for rounding up residents’ signatures on gas leases. In October, the group’s newsletter noted that $39,300 had already been received, with more expected.

Some residents later smelled a rat after learning that negotiations were held only with Four Sevens, despite the availability of numerous other gas companies willing to bid. Homeowner Pete Fletcher, who had already signed the lease presented by Woodhaven Community and Four Sevens, later set up a neighborhood meeting. He invited a competing gas driller, Llano Royalty, to attend, and a Llano official pledged to pay more than Four Sevens. Fletcher and others wondered why Woodhaven Community Development hadn’t encouraged competitive bidding. They became suspicious after hearing rumors of a large contribution to the nonprofit group — money which some residents felt was taken from their shares.

Fletcher said a Four Sevens official told him that no money was given to Woodhaven Community Development for enlisting residents. Later, though, Fletcher learned that the gas company offered a $90,000 contribution. He asked Woodhaven Community Development board member David Kenny about it and said the RiverBend Bank executive acknowledged the contribution. According to Fletcher, Kenny said the tax-exempt group was relying on “creative accounting” to accept the money as a gift rather than as earned income.

Kenny said he doesn’t recall using the words “creative accounting” but recognized that the contribution from Four Sevens would need legal clarification. Advisors told the nonprofit group that using only volunteers to do the legwork for Four Sevens meant that a subsequent contribution could be tax exempt, he said. Also, he said, Four Sevens was already firmly established in the area, offered a deal similar to other recent leases, and enjoyed a solid reputation. “There is nothing in the world wrong with competitive bidding, but it was done very fair and at the time it was as good a deal as I had heard of in this area,” he said.

Disgruntled residents should also consider that the nonprofit group paid $6,000 for an attorney to draft the lease agreement with residents, he said.

Longtime Woodhaven resident Allen Sanders was furious when he learned about the contribution to a nonprofit group that claimed to represent his best interests. “They hid it,” he said. “When I found out, I had already signed the lease.”

Kenny said the neighborhood association’s president also serves as a board member at the nonprofit group. “The president of the neighborhood association was informed all the way through and in fact was reporting back to the steering committee of the neighborhood association,” he said. “It wasn’t sneaky in any form or fashion.”

Attorney Rick Disney, who donates his services to the nonprofit group, doesn’t understand the fuss. He told the Weekly that the contribution would go back to the community. The nonprofit’s mission is neighborhood development and improvement.

Sanders criticized the group for putting itself in a position of representing homeowners. Woodhaven Community Development doesn’t hold public meetings or publish financial statements and “has no obligation to anybody in the neighborhood except themselves,” he said.

Disney said he felt comfortable that the contribution was legal. But nonprofit watchdog groups aren’t as comfy.

“For Woodhaven Community Development to even take on the mediation role between the gas driller and the neighborhood residents seems like a conflict of interest ... especially with a $90,000 contribution in the works,” said Naomi Tacuyan, a spokeswoman for the National Committee for Responsive Philanthropy “It’s not the illegality of it, it’s the nonprofit posing as an advocate for the community and not taking their best interest in consideration.”

Barry Silverberg, executive director of the Austin-based Texas Association of Nonprofit Organizations, said a contribution, by definition, means no services were rendered. But in this case, he said, it seems that “services were sought and provided in return for a payment.”

Creative accounting shouldn’t occur in an arena that relies on public trust, he said. “In the nonprofit sector, if something doesn’t look good, it’s not a good idea to engage in it,” he said. “The fact that this transaction appears to be clouded, either legal or not legal, would from my perspective call upon the nonprofit to explain in direct terms what exactly transpired. Clearly a service was provided.”

In October, the community development group published a bulletin saying Four Sevens didn’t have the resources to contact the 1,000-plus Woodhaven property owners and solicited the nonprofit’s help. The group also thanked Four Sevens “for the $39,300 contribution that it made in September.”

Several people said officials at the nonprofit group have claimed the $90,000 contribution is dependent upon enlisting the remaining residents for Four Sevens. That alone suggests money is being paid for services rendered, Silverberg said. “If they’re booking that $90,000 as a charitable contribution, they are going to have trouble with the IRS,” he said.

The gas lease controversy is one of many flaps surrounding Haskin and Woodhaven Community Development. Homeowner Norman Bermes was president of Woodhaven Neighborhood Association in 1996 when he and others proposed creating an economic development group to help attract businesses. Retired businessman Joe Epps was named president of the new group and sought nonprofit status for it. Numerous board members were named, but Bermes, Fletcher, and others said Haskin was the group’s primary leader.

“Woodhaven Community Development is Becky Haskin,” said Louis McBee, who unsuccessfully challenged Haskin in the May city council election.

Bermes, a computer consultant who works with after-school programs at nearby apartments, said the group’s main focus has been targeting apartments and their tenants, who don’t fit into the group’s vision of the neighborhood. This isn’t what he envisioned for an economic development group.

Neither Haskin nor Epps returned phone calls regarding this article.

Haskin was at first listed as a board member but later gave up that title after city attorneys noted the potential for conflicts of interest. As a city council member, Haskin voted on neighborhood issues and solicited funds for projects in which the community development group had a clear interest. Despite her absence from the board, Haskin’s influence remains obvious.

“It amazes me how much she is able to get by with,” Silcox said. “She helped form the community development group, and then she got off of it, but when they sat down with Four Sevens, she was in the room with them. That ain’t right.”

Kenny said he couldn’t recall whether Haskin attended the board of directors meeting when the gas lease proposal was discussed but said she regularly attends those meetings. “I would assume she would have been there,” he said. “Becky’s experience when it comes to how things work in the city ... is a tremendous help. [But] we go to vote on something, Becky’s got no vote.”

Tenants at area apartments include many low-income minorities who migrated to the once-predominantly Anglo neighborhood after fair housing laws were beefed up in the 1980s. Apartment managers have accused Haskin of exaggerating crime problems to justify filing nuisance abatement lawsuits. Haskin convinced the city council to pay $236,000 for a neighborhood master plan, which would tap government funds to tear down apartment complexes and make way for town homes, single-family houses, and a landscaped gateway. A tax increment financing (TIF) district could then be established to attract businesses.

Silcox compared the scenario to using the city’s power of eminent domain.

“She wants the government to go in there and take down those apartments,” he said. “The bottom line to all of this is somebody is going to make some money off this deal. I find that insulting as hell to the taxpayers.”

Email this Article...

Email this Article...