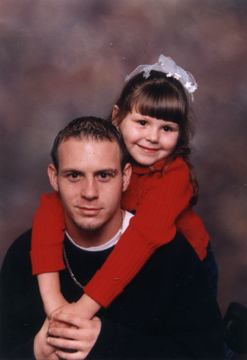

Christopher Sellers in a rare moment of relaxation with his young daughter.

Christopher Sellers in a rare moment of relaxation with his young daughter.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Hard Time

Parents and attorneys question the tactics used by a Johnson County task force in one man’s case.

By PETER GORMAN

Three hits of LSD and a joyride in a stolen car don’t usually add up to life in prison, even if Christopher Sellers were guilty of delivering the first and knowingly doing the second. But those charges and Chris’ own apparent inability, at some points, to stay away from drugs have added up to a very high price for a young man caught up in a Johnson County legal system that is described by critics as anything from corrupt to just mean-spirited.

Sellers has spent more than five of the last seven years in jail. Now he faces the prospect of accepting a deal for four more years in jail or going to trial with the chance of getting a sentence of up to 99 years, because of charges that his parents say are based on a no-warrant search by a controversial Johnson County drug task force that, the elder Sellerses say, produced nothing, as far as they could see or were told.

“Don’t get me started on Johnson County,” said Sellers’ Fort Worth defense attorney, Jim Shaw. “You don’t want to know what I think about the legal system there. All you have to know is that in Chris’ case, it was wrong from the gitgo. ... And it’s going to get worse.”

The story of Chris Sellers, 24, is one that occurs a hundred times a day, all over the country, not just in Johnson County. And it’s no angel’s story — many will see his offenses as serious crimes for which he’s getting his just desserts. But it’s also the story of getting caught up in the system and then not being able to find a way out — sort of like wrestling with Chinese finger-cuffs: The harder you pull, the tighter they get. In Sellers’ case, the story includes an abusive prison situation from which he was removed by an official in one county — and therefore punished by another county. And other teens who recanted their accusations against him, too late.

Sellers’ blue-collar parents moved him from Arkansas to the Fort Worth area in 1986 when he was five and then to Burleson when he was in the ninth grade. Early on, as a small kid pushed around by bigger ones, a blue-collar kid passed over by privileged kids, Sellers developed an attitude, his father said. (Years later, he would be diagnosed as suffering from bipolar disorder and attention deficit syndrome.) But Chris’ real problems didn’t start until he dropped out of school at 17 and fathered a baby. And it was shortly after he became a dad that he went to a party where someone offered him LSD. Sellers says he turned it down, but that three other teens accepted — and one of them wound up in a local hospital as a result. At the hospital, one teen-ager, still under sedation, told police the drugs had come from Sellers.

A few weeks later, in December 1998, police stopped him near his house and searched him for evidence relating to a recent act of vandalism. The officers didn’t find anything related to the vandalism, but they did find the butt of a marijuana joint, and Sellers was charged with misdemeanor possession of pot.

Then, several weeks later, the Johnson County sheriff’s office filed charges against Sellers on the LSD charges — three felony counts of delivering a controlled substance to a minor. And before that case could come to trial, Sellers was stopped by police while driving a stolen car. Sellers said a friend had told him he’d just bought the car and let Sellers take it out for a spin. Johnson County charged him with a misdemeanor for “unauthorized use of a vehicle,” but the dealership from which the car had been taken was in Tarrant County, and prosecutors there soon added burglary of a building to his growing list of charges, since the dealership building had been broken into to get car keys.

A Johnson County judge allowed Sellers to stay out on bond, but added the requirement that he undergo routine drug tests. Three months later, when Sellers turned up with traces of pot in his urine, the judge ordered him into a recovery program that would last until he turned 18, in August 1999.

When his case came up for trial in September 1999. Johnson County prosecutors offered Sellers a deal: For the three counts of delivery of a controlled substance, the misdemeanor pot possession and unauthorized use of a vehicle, they offered to allow Sellers to undergo nine months of drug rehabilitation at the Jester I Unit of the state prison in Richmond, near Houston, followed by 10 years probation. If he rejected the deal and went to trial, he could have gotten 10 years in prison.

Although he still maintained his innocence on the drug delivery charges, Sellers signed off on the plea bargain. Before he could be shipped off to the Richmond prison unit, one of the teen-agers who’d told police that Sellers had given her the LSD recanted — and in a new statement, backed up Sellers’ contention that the drug came from the same young man that Sellers had named as offering it to him. Sellers’ attorney, at the insistence of a Johnson County prosecutor, filed a motion for a new trial, but the judge turned it down. Sellers, the judge pointed out, had already pleaded guilty. (Since then, a second teen has also recanted the same allegation against Sellers.)

But North Texas prosecutors weren’t quite done with him. Tarrant County went forward with the burglary charge related to the car theft. Again, Sellers, now a few months past 18, continued to protest his innocence but agreed to accept a guilty plea in return for deferred adjudication — the promise that if he completed the prison drug program and stayed clean for five years, the crime would be wiped off his record.

It wasn’t as easy as it sounded. Abuse by the guards at Jester — attested to by all five of Johnson County’s inmates in the drug program at the time— was rife: Inmates had to buy food and soft drinks for the guards if they wanted to go to the commissary to buy anything for themselves; beatings were a normal course of events; white prisoners had to stand naked weekly in front of the entire prison population for two minutes at a time; sex was forced on some of the prisoners by the guards. Those who refused to play ball with the guards were written up for bad behavior and sent to solitary confinement. And then they were drugged.

“They called it the Thorazine Unit,” Sellers’ mother Renee told Fort Worth Weekly. “There were times we went to see Chris when he was so doped up by the doctors there he had no idea Fred and I were in the room.”

The allegations of abuse, initiated by several of the Johnson County inmates, made their way to probation officer Kelli Stevens, Johnson County coordinator of the drug program. She was skeptical. Stevens’ superiors would not allow her to discuss the problems at Jester I, but according to copies of her notes provided by Renee Sellers, Stevens had heard of guards abusing several young inmates from Johnson County as early as December 1999 but didn’t consider the reports reliable. But by July 2000, the complaints were too overwhelming to ignore. And in late August, when she discovered that the 18-year-old Sellers had been put in the general population of the Jester lll maximum security unit of the state prison because a cigarette had been found under his mattress, she pulled all five Johnson County inmates from the program. They were returned to Johnson County and placed in a halfway house run by the Volunteers of America.

Even that improvement, however, became a serious disadvantage for Sellers. Tarrant County prosecutors, counting the removal to the halfway house as a breach of Sellers’ plea agreement on the burglary charge, picked him up from that facility and — after four months in the county’s Green Bay lockup — convinced a Fort Worth judge to sentence him to another 14 months in prison. He served it in a unit at Jacksboro, northwest of Fort Worth, and got his high school equivalency certificate while he was there.

Time inside apparently hadn’t scared Sellers all the way straight, however. He got a job, got married, but continued to use drugs. And to miss appointments here and there with his probation officer. He’d only been out nine months when a Johnson County judge revoked his probation and sent him back for another five years in prison.

This time, Sellers actually served 18 months. According to his folks, however, Sellers came out of prison tattooed, angry, and “just different.” Still, this time, he managed to keep his nose clean for more than a year.

In January 2005, however, trouble rolled up to Sellers’ parents’ house in Burleson in the form of three officers from the Johnson County narcotics task force.

“The door was open, and two of them walked into the house,” Renee Sellers said. “They were wearing task force vests. They didn’t have a warrant or say a word. One of them just walked to the back of the house, to Chris’ room,” she said. Chris himself was in the kitchen.

“I was scared,” Renee Sellers said. “I called my husband Fred and he came right home. When the officers left, they had nothing in their hands. Absolutely nothing. They never said they found anything either.”

Several weeks later, however, at his second parole visit after the task force search, Sellers was arrested on a drug charge. The task force officers claimed they’d found a small quantity of the party drug Ecstasy in a lockbox in Chris’ room. He spent three months at Green Bay and the last year at Johnson County Jail waiting for a trial on the new charge.

Renee said she never gave the officers permission to search the house. Chris denies he gave the officers permission to search his room or the lockbox where the drugs were allegedly found. An official with the Johnson County narcotics task force told the Weekly that, by directive, they never enter a premises without a signed “consent to search” form. But Shaw, Sellers’ attorney, said he has never been provided with any such document regarding that search.

The Weekly tried to determine whether task force members logged any drugs as property seized from the Sellers’ house that night, but a spokesperson for Commander Adam King declined to release that information because the case is ongoing.

Shaw said that the Johnson County narcotics task force has a reputation of “playing fast and loose with the law.” Several other defense attorneys, as well as one former task force member, echoed Shaw’s sentiments.

Robert Kersey, a Granbury attorney, said he’s had clients “pulled over by task force teams wearing hoods on their heads. I’ve had clients have to stand outside their homes half-dressed for hours in 50-degree weather until they signed ‘consent to search’ forms. They bully people, they bend the rules, they cut corners. And then they get together with a prosecutor before a trial and get their stories straight.”

One Tarrant County paralegal who didn’t want his name used said, “I know the Johnson County narcotics task force is bad. Will they lie? Yes. Might they plant drugs? Anything is possible with them. And I mean anything you can imagine that is outside the law is possible.”

Despite the questions over the search, several defense attorneys said, Sellers would be wise to take the plea and do the four years prison time, because there is little chance of him winning a swearing match with the task force.

“They’ve got him by the balls,” Fred Sellers said. “If my son takes the plea and does four more years, he may never be able to adjust when he gets out. And if he goes to trial and the jury convicts him, he’s liable to get 20 years. And for what?”

Email this Article...

Email this Article...