|

|

Sharon Macauley, shown with her granddaughter, died after a hip operation at JPS hospital.

Sharon Macauley, shown with her granddaughter, died after a hip operation at JPS hospital.

|

Macauley’s family has never been given an autopsy report or any details about how she died.

Macauley’s family has never been given an autopsy report or any details about how she died.

|

Ramona Holcombe’s husband, Peter, left, died just before she entered prison. Friend Kathy Daic, center, believes Holcombe, right, was a victim of swindlers and then of Carswell.

Ramona Holcombe’s husband, Peter, left, died just before she entered prison. Friend Kathy Daic, center, believes Holcombe, right, was a victim of swindlers and then of Carswell.

|

Holcombe and a young friend enjoy an outing at Disneyland several years ago.

Holcombe and a young friend enjoy an outing at Disneyland several years ago.

|

Tracy Sanchez drew a long prison term for drug dealing, but neglect of her medical problems while in custody could be a death sentence for her.

Tracy Sanchez drew a long prison term for drug dealing, but neglect of her medical problems while in custody could be a death sentence for her.

|

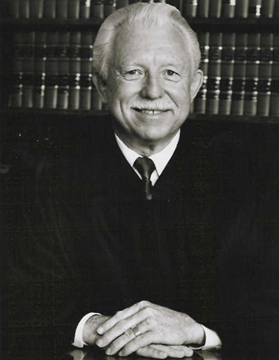

Sears: ‘We treat prisoners suspected of terrorism better than Carswell treats its inmates.’

Sears: ‘We treat prisoners suspected of terrorism better than Carswell treats its inmates.’

|

Darlene Fortwendel, at right, finally received a compassionate release after Carswell misdiagnosed and failed to treat her liver cancer. She died last month.

Darlene Fortwendel, at right, finally received a compassionate release after Carswell misdiagnosed and failed to treat her liver cancer. She died last month.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Taking the Cuffs Off at Carswell

A retired judge and a former staff physician are demanding reform at a Fort Worth prison hospital.

By BETTY BRINK

“I believe there should be a congressional investigation and based on those findings, I would expect criminal charges to be filed against those persons who have inflicted pain and suffering on the inmates, as well as those in authority who condoned these practices. These women have been subjected to cruel and unusual punishment and their constitutional rights have been violated.”

The speaker is no radical prison reformer, but a retired judge who spent 12 years on the state appellate bench in Texas, two years as Harris County district attorney, and more than a decade as a criminal defense attorney. And the inmates Ross Sears is describing are not being held in some distant dictator’s jails, but in Fort Worth, at the Carswell Federal Medical Center for women.

Sears has become the latest to add his voice to the growing crowd of those expressing outrage at what is going on at Carswell, the only — allegedly — full-service federal prison hospital for women in the country. “Inmates have died under suspicious circumstances, they have been denied critical medical care and necessary medication, they have been given the wrong medication with serious results, they have been the victims of retaliation when they complain, and they have been assaulted and raped,” he said. “I am convinced these events have occurred, and I am convinced Congress will do something about it. We treat prisoners suspected of terrorism better than Carswell treats its inmates, and we must make sure that those responsible for this inhumane treatment are themselves incarcerated.”

The calls for investigation and reform at Carswell have been coming for years from those who spent time inside the prison hospital’s walls, and from the families of its current and former inmates. But now, in addition to Sears, the howls of outrage are also coming from one doctor who saw the conditions at Carswell first-hand.

Dr. Roger Guthrie, former medical officer in Carswell’s family practice clinic, last year took his complaints to the U.S. Office of Special Counsel, after four years of trying to effect change from the inside. In his filing, Guthrie described repeated episodes in which he believes inmates were endangered or died unnecessarily because of medical mistakes, substandard care, and unconscionable delays, in a prison setting in which inmates were raped, documents falsified, records kept haphazardly, and taxpayer money wasted.

At least one of the cases of what he called medical malpractice apparently is now under investigation by the special counsel’s office. “I have been called numerous times by the OSC investigator asking for more details on that case,” Guthrie said.

Sears, too, is ready to take the Carswell case to federal authorities. He plans to take his extensive evidence of medical neglect and abuse to influential friends in Washington D.C. and to press for a full Congressional investigation. He’s hoping the political connections he built during his years in state electoral politics can now be used to help one of the most politically powerless groups in the country — the elderly, ill and dying women in the United States’ federal prison system.

Calls and e-mails to Carswell spokeswoman Debra Denham, requesting comment for this story, have not been answered. Bureau of Prisons spokesman Mike Truman did not call back with answers to specific questions. A request made to the bureau last August under the federal Freedom of Information Act has not been fulfilled.

Sears was drawn into the Carswell drama by the case of a client, Ramona Holcombe, for whom he is seeking a compasionate release, and who he said has been “grossly medically neglected and abused.”

“And I fully expect,” he added, “that those in control at Carswell will retaliate against Ramona Holcombe as they have against many other inmates who have been brave enough to speak out against this intolerable atrocity. If that happens, it will only confirm what these inmates have been telling anyone who would take the time to listen, and the legal system can repay those responsible.”

The retaliation may have already begun, he said. Holcombe’s request for compassionate release was just denied.

No wild-eyed radical prison reformer, the 73-year-old, white-haired Sears has spent most of his retirement years serving as a visiting judge and in dispute resolution cases, working quietly from his home in Missouri City just outside Houston. He knew nothing about the conditions at Carswell until a friend asked him to represent Holcombe, 66, who had been sent to Carswell in 2002 following her conviction for a white-collar crime.

“I was appalled at what she told me,” he said.

Holcombe’s implausible route to prison was traced by Sears and the mutual friend, Kathy Daic of Houston, in a recent conference call. Holcombe, whom Daic has known for 15 years, had founded a charity in West Virginia to raise money to open a lakeside retreat for abused women and children. She was married, the mother of four grown children and seven grandchildren. “She was very trusting and naïve,” Daic said. In 1998, Holcombe was approached by two men who promised her she could make hundreds of thousands of dollars for her retreat if she would help them find investors for what Sears says was nothing more than a Ponzi scheme, Holcombe bit, and her legitimate charity was used as a front until the scheme collapsed. In 2001, Holcombe and one of the men were convicted of fraud. The other one is still on the run.

Sears and Daic are both convinced that Holcombe was as much a victim as those who invested. “She was used, her charity was used, and when Ramona realized what had happened, she took what money she had and paid back some of the investors,” Sears said. Still, a federal jury found her guilty of fraud and sentenced her to eight years.

A prison sentence, however, turned out to be only the beginning of her troubles. Her husband died just before she started serving her sentence. And shortly after she arrived at the Victorville federal facility near Adelanto, Calif., she was diagnosed with breast cancer.

In a telephone interview from Carswell, backed up by copies of her medical documents, Holcombe told Fort Worth Weekly the story that appalled Sears. In late October 2001, she had a mastectomy of her left breast at a hospital near the California prison. Doctors inserted an inflatable disc in the empty pocket to allow the skin to grow, stay pliable, and stretch until she could undergo reconstructive surgery. The process requires careful monitoring by a surgeon in two-week intervals as the skin stretched and healed, until the insert could be removed and a saline implant inserted, according to her medical reports. The procedure must be done “in three to six months,” one doctor wrote. If infection develops, he wrote, the temporary disc must be removed “within 24 hours.”

Back in prison, Holcombe said, the insert began deflating and the plastic rim pushed painfully into her chest cavity. Nothing was done about it in California; instead, in April 2002, she was sent to Carswell, with the assurance that there she would receive all of the care she needed.

Once at the Texas prison facility, “I was seen by Dr. [Roger] Guthrie,” she said. Her breast tissue was breaking down and the plastic ring had punctured her skin, causing an infection. Guthrie was able to get her to a plastic surgeon by May, who told her that she needed immediate surgery to replace her damaged breast tissue. But it wasn’t until the end of August that her surgery was finally approved by Carswell “after many months of pain,” the inmate said.

By then the plastic ring was protruding from her skin and the surrounding area was still badly infected. The surgeon removed the rim and took skin and muscle from her back to repair and replace the damaged breast tissue. Reconstructive surgery was no longer an option, she was told, because the long delay in treatment had caused irreversible damage to her breast tissue. The medical reports also show that a “hardened diseased capsule” had to be removed from under the temporary disc. Now, instead of a new breast on her left side she has a large sac of fatty tissue under her left arm due to fluid build-up, a still-painful scar that goes from her chest to the middle of her back and an “ugly, hard, small knot” where her left breast used to be. She is still in constant pain, she said, and “disfigured for life.”

Holcombe also arrived at Carswell badly in need of knee surgery. When she was finally taken to an outside hospital, she was told by the doctor that for full recovery she needed a complete knee replacement, but that Carswell would only pay for orthroscopic surgery. The partial fix has left her unable to walk. “I am now wheelchair-bound,” she said. And at Carswell, being stuck in a wheelchair can have dire consequences for inmates.

Holcombe is housed on the fifth floor at the prison hospital, with 90 other patients, about half in wheelchairs, she said. All of the women have to get themselves downstairs to the first floor to go to sick call for their medicines and to the cafeteria for their food. “We are down to three working elevators,” out of six, she said. Since one elevator holds five wheelchairs and the others hold no more than two, “It is impossible for many of us in wheelchairs to get our meds or get to the cafeteria to eat because they close everything down before we can get there.”

One ex-inmate, Barbara Winton, described the fifth floor as being “the twilight zone.” The women there looked like “walking skeletons, zombies,” she said.

Holcombe said Carswell officials wouldn’t let her take the vitamins and mineral supplements that she had been using to keep her cholesterol down, but apparently have no such ban on pain medications. “They are always pushing drugs on us, Oxycontin, Percocet, Vicodin” — all of them narcotic painkillers — “we can get those whenever we want.” Holcombe, who said she turns down painkillers, believes such drugs are made readily available in order to keep the women sedated and under control. In the meantime, she said, her “bad”cholesterol level has soared from 165 to 266, high enough to put her at substantial risk of heart disease.

Holcombe not only opened Sears’ eyes to her medical horror stories, she also passed on to him the stories of the other women that she knew. Sears began to document the cases — in part through contacts provided by the Weekly’s stories on Carswell dating back to 1999. He started talking to inmates and their families, like the children of Sharon Macauley, who were devastated to learn in December that their 67-year-old mother had died following hip surgery at John Peter Smith Hospital, the outside contract hospital for the prison.

Macauley, who was in the horse business in California, was incarcerated for taking part in an illegal horse-selling enterprise. She was sent to Carswell in 2004 because of a pre-existing heart condition, and was due to be released late this year. While at Carswell, she fell and broke her hip.

Her son Rich told the Weekly that he and his four siblings didn’t even know his mother was having surgery until they were called by Carswell to tell them she was dying. They got flights to Fort Worth right away, Rich said, but she died an hour before they arrived. “It gave them time to get the handcuffs off that she must have had on because of the deep bruises on her wrists,” he said.

Since then, the family’s grief has been turned to anger by the prison’s stonewalling of their requests for information about Macauley’s death. At first they were told that there would be an autopsy by the Tarrant County Medical Examiner’s Office, as was once routine for all deaths outside the prison. “We thought that at least we would get some answers,” Rich Macauley said. But when he called the county coroner, “I was told the county never does the prison’s autopsies.” His calls to the prison since then haven’t been returned. “To this day, we haven’t found out one thing,” he said. “It’s like she disappeared off the face of the earth. This boggles my mind. I would have never believed this could be happening in my country.”

Autopsies have been a problem for another family. When 28-year-old Mari Ayn Sailer died in her bed at Carswell in September 2005, following days of complaints to the doctors and nurses of difficulty breathing and other flu-like symptoms that were ignored, her family asked for an autopsy. They — and the Weekly — were told that it would be done by Tarrant County. When the Sailer family called the county office, they were told that Carswell had cancelled the autopsy, telling the medical examiner’s office that the prison would do the procedure. To date, the family has never received any autopsy results. Officials told the Weekly that the county quit doing the prison’s autopsies two years ago.

Guthrie, who is no longer with the prison, said Bureau of Prisons policy is clear: Autopsies must be performed whenever there’s a death at a prison, preferably by the coroner in the county where the prison is located.

Guthrie and Sears want an investigation of the deaths of women like Sailer and Macauley, whose families want answers. But they worry even more about women who are still hanging on at Carswell, in desperate need of medical care they’re not getting.

“I don’t want to die. ... Time is not on my side.” The words are from a letter Tracy Sanchez wrote to President George W. Bush in September, pleading for a pardon for her crimes. It is her last resort.

Sanchez is not on death row — at least not in the traditional sense. Since 2003, she has been an inmate at the Carswell Federal Medical Center. The 36-year-old mother of five from Utah suffers from a rare, genetic kidney disease and is facing death in less than a year unless she gets a kidney and liver transplant. She knew her crime was wrong, she wrote, but it was not a death penalty case. “Why should I now be required to pay with my life?”

Sanchez is in her third year of a 30-year sentence for her role in a narcotics ring that operated mostly out of a Mexican import shop she helped run in Ogden. But without the transplant, her doctors say that Sanchez will never leave the prison alive. She is suffering from end-stage renal failure due to a disease known as primary hyperoxaluria, or oxalosis. In 30 years of practice, Sanchez’s renal specialist Charles Andrews said, he has seen only three cases of it. Sufferers are born with an enzyme deficiency that allows oxalic acid to build up in the kidneys, binding with calcium to form hard, crystal-like deposits that “plug up the kidneys” and eventually spread into all of the patient’s tissues, he said. The condition is characterized by severe pain and leads to kidney failure, irreparable liver damage, cardiac arrhythmia and death. For now, Sanchez is being kept alive through dialysis, but that is a temporary fix.

Sanchez was diagnosed in 1997 after her sister Amanda died of complications of the same disease. At the time of her arrest in 2000, Sanchez was on a waiting list at the University of Nebraska for the double transplant, a slot she lost following her conviction. Two of her Utah doctors wrote to the judge in Sanchez’s trial urging continued aggressive treatment for her disease while in custody, including the transplant; otherwise, they said, she would face “kidney failure and death.” One wrote that “for the sake of her health ... her management would be a lot safer and easier outside the prison system.” That didn’t happen. She was sent to Carswell by U.S. District Judge Dale Kimball of Salt Lake City, who assured her, according to court transcripts, that she would “receive the best medical care available” at the federal hospital — including being put on a transplant list in Texas.

“It is an unfortunate social fact,” Andrews told the Weekly “that she got lost” in the system from the time of her arrest until Andrews saw her at Carswell three years later. By then, the specialist said, her disease was significantly advanced. In July 2004, Andrews wrote to Carswell medical director Tecora Ballom that Sanchez then faced a life expectancy of less than two years without a liver and kidney transplant. If the prison was not willing to provide the procedure, he urged that she be granted compassionate release “where she can return to the outside support systems that may be able to provide the necessary transplant ... .”

Thus began a grindingly slow process by which the Bureau of Prisons dealt with her request. Finally, 16 months later, in November 2005, the bureau allowed her medical records to be sent to the Baylor Regional Transplant Institute so she could be evaluated for a transplant. It was a rare victory for a Carswell inmate. In the 12 years the hospital has been open, no transplant has ever been approved.

But it was too late. The Baylor staff determined that Sanchez’s disease was by then too far advanced for a transplant to save her life. Andrews, who is a contract physician for Carswell and has treated Sanchez since 2003, appealed the Baylor decision but was again turned down. Her former doctor in Utah, Martin Gregory, her federal public defender attorney Vicki King-Mandell, and Andrews urged the prison to approve compassionate release in order to allow her to go home and be re-evaluated by another transplant team that might result in a different outcome. Or at the least, “allow her to go home and be with her children,” King-Mandell said.

That request was denied in February. The Bureau of Prisons’ general counsel, Kathleen Kenney, wrote to Carswell Warden Ginny Van Buren that while Sanchez’s medical condition made her eligible for such a release, the seriousness of her crime “made it inappropriate to release [her.]” In spite of the fact that her medical records show that she is on dialysis three times a week, is wheelchair-bound, has blurred vision, suffers from neuropathy, frequent nausea, blood pressure drops, has had three surgeries to replace her catheter, and on many days is “too ill to get out of bed,” Kenney wrote that Sanchez still had “her ability to re-offend, if released.” In a Kafkaesque afterthought, she noted that Sanchez’s “projected release date is Dec. 15, 2024, via Good Conduct Time.” Or a miracle.

Kenney did not return calls from the Weekly. Sanchez appealed to Judge Kimball for relief. On April 7, he wrote that after sentencing, he lacked authority to overturn a Bureau of Prison’s decision.

The prison agency touts the medical care at Carswell as “comparable to community standards.” Yet in more than seven years of reporting on Carswell, the Weekly has documented an ongoing pattern of medical incompetence, neglect, bureaucratic indifference, and sexual abuse that has caused months and years of unnecessary suffering to some inmates, shortened lives, and contributed to untimely deaths.

One of the women in that pattern was inmate Darlene Fortwendel, 49, who died on April 26 in a hospital in Tell City, Ind., surrounded by her family. Her rare liver cancer was misdiagnosed at Carswell for months and then, inexplicably, never treated. In August 2005, after a long battle waged by her tenacious sister, Fortwendel was sent home under compassionate release. “We are thankful that we had her here at home for these last months,” sister Angie Garrett said, “but we will always believe that Carswell was reponsible for her suffering and her death.”

In every such case reported by the Weekly, the charges have been documented by some combination of hospital records, transcripts of court proceedings, letters and documents and interviews from those directly involved.

In 1999, inmate Cynthia Lyda walked into Carswell with a psychiatric disorder but was otherwise healthy. Today, according to Dr. Guthrie, she is confined to a wheelchair, unable to dress herself or even find her way to the cafeteria. She sustained irreversible brain damage following a two-hour seizure last year that another prison doctor ignored because he believed she was faking, Guthrie said. By the time the doctor decided the seizure was real and sent her to the emergency room at an outside hospital, she was almost dead. The 39-year-old woman spent several weeks at Huguley Memorial Medical Center in intensive care before being sent back to Carswell “severely brain-damaged due to [the] delay. ... She can’t do anything for herself,” Guthrie said.

A medical professional ignoring a seizure is one outrage, he said. The greatly increased cost of her care, now and for the rest of her life due to such negligence, is another. Guthrie’s anger extends to the prison, which took no disciplinary action against the doctor or held anyone responsible.

Believing that an inmate is faking is the rule, not the exception, at Carswell, he said. “It is common among the staff to think that every woman who presents herself at sick call is initially faking,” he said. The end result of such an attitude has been “too many cases of either brain damage or death,” the Colleyville physician said.

Guthrie no longer works at Carswell. “I got fired on trumped up charges,” he told the Weekly, “because they knew I was about to blow the whistle on the inmate abuse and the huge waste of taxpayer dollars going on at that place.”

The Lyda case is just one of many that Guthrie cited in the complaint he filed last June with the U. S. Office of Special Counsel, the agency set up to investigate federal employees’ whistleblower complaints. Included among the details he provided of medical and bureaucratic failings and illegal conduct at the prison hospital was his description of an appalling system for keeping medical records.

Staff meeting reports and assignments are verbal, he said, with no written records kept, and results of emergency room visits are not recorded. Requests for outpatient surgeries and trips to specialists are often delayed or lost. Biopsy reports take weeks to be returned to physicians. Cardiology workups for surgery take six months.

Guthrie was the family practice doctor for the entire hospital population — about 500 patients at any given time. He was fired in April 2005 in spite of a file filled with outstanding evaluations. The file is also filled with his memos complaining to Warden Van Buren and medical director Ballom, almost from day one of his hiring, about the incidents of misconduct and waste that he listed in his federal complaint. “It is no secret that I was going to blow the whistle if things didn’t change there,” he said.

But before he got his chance to do so, he was injured in an accident at work. While Guthrie was at home on sick leave, Van Buren wrote to him that his contract would not be renewed. Two Catch-22 cases were cited. He was blamed because one of his patients had to wait six months for a thyroidectomy — due to lost paperwork by the hospital committee that must approve surgery requests. The other had to do with a patient who refused to take her thyroid medicine. He was written up by the medical director, he said, for refusing the director’s order to correct the problem by “increasing the dosage of the meds that [the patient] wasn’t taking in the first place.”

“Carswell is run by a bunch of incompetents, and those few [health care professionals] who want to practice good medicine either leave in disgust or get fired, like I did,” he said.

Guthrie, 57, joined the staff at Carswell in 2001 as a general practice medical officer after quitting a nearly 30-year career as an obstetrician-gynecologist and family practitioner in Hurst. By then, he had delivered more than 3,000 babies, he said, and survived a messy lawsuit over the death of one infant after a particularly difficult delivery. “I was tired,” he said. “I was ready to let someone else do the paperwork and take the risks.” He lasted four years at the federal center, but he started almost immediately to wonder just what he had gotten into.

Right away, he began to witness — and document — what he said was a hospital out of control: incompetent medical care, cover-ups of medical mistakes, hustling near-death inmates off-site so that the hospital’s death statistics would look better, and an overworked staff. Many doctors and nurses who resigned or were fired were not replaced, he said. By the time Guthrie left, six physicians from the required staff of eight had left (one was kicked out for sexual abuse of inmates) and only three of the six openings had been filled.

Worse, he said, the health profession’s credo to “do no harm” was callously ignored. In his whistleblower complaint, Guthrie laid out a litany of what he called medical malpractice cases that he witnessed — everything from an inmate with a fractured hand that went undiagnosed for four weeks in spite of her continuing trips to sick call with complaints of pain, to patients “too numerous to count” who waited as long as 15 months for badly needed hysterectomies and hip replacements. Cancers were routinely misdiagnosed or were not diagnosed until it was too late due to lengthy delays between tests and test results. The patient who waited six months for goiter surgery in the case used to fire him, he said, developed heart trouble because of the delay. “It was frustrating as hell.”

But the case that caught the attention of the special counsel’s office, he said, was Lyda’s.

“What happened to her is an outrage, morally and financially, and I’d love for a lawyer to have been called,” Guthrie said. But there has been no outcry, he said, because Lyda’s family has abandoned her. She has been diagnosed with Munchausen Syndrome by Proxy, a disorder in which a person seeks attention by causing someone they are caring for to be constantly ill. In 1999, Lyda pleaded guilty after being caught on a hospital video monitor tampering with the feeding tube of her critically ill 5-year-old son, nearly killing him. By 2007 her sentence will be finished, but she will have to be institutionalized somewhere for care. The special counsel’s office, he said, is now the only avenue of holding accountable those responsible for her condition.

Loren Smith, head of the OSC office of public affairs said he could not “confirm or deny” that any official investigation is in progress.

Guthrie was also under the gun, he believes, because of a couple of embarrassing memos he wrote on Feb. 24, 2004, a day after the alleged suicide by hanging of inmate Linda D’Antuono Fenton (“Hospital of Horrors,” Dec. 19, 2005). An attempted suicide is the worst thing that can happen in a prison hospital, he said. It goes to the heart of what is known as a “sentinel event,” in medical parlance a death or serious injury at a hospital caused by neglect, deliberate or accidental, on the part of the staff.

Hospitals are expected to report such incidents. In the United States, he said, “studies show that about 100,000 people die every year due to medical mistakes. But Carswell with its high-risk patients, known rapes, documented cases of medical malpractice, unexplained deaths and attempted suicides, hasn’t reported a sentinel event in the last ten years, including Fenton’s [death].”

Guthrie was the doctor who responded to the code-blue call the morning that Fenton was found unconscious in a cell with a sheet knotted tightly around her neck. He was also the official recorder of the incident. In memos to Ballom, made available to the Weekly, he charged that he was asked by two prison officers to change the “times of record and response” recorded in his medical report: “I was asked by [the officers] to change the time that I arrived on the scene from eleven [a.m.] to eleven-thirty.” He refused.

Guthrie believes he was asked to falsify his report in order to make it appear that he arrived on the scene only shortly before outside paramedics showed up. However, the physician said, the paramedics didn’t arrive until long after he reached Fenton’s room. When Guthrie arrived, he thought she was dead. But he and others worked on her and got her heart started and some level of breathing, he said, before the outside paramedics arrived. Guthrie said he found out later that the emergency ambulance personnel weren’t called until 40 minutes after Fenton was found. She died eight days later at Fort Worth Osteopathic Medical Center without ever regaining consciousness. Guthrie said he has no idea how long she had lain near death and unnoticed before he was called. But medical reports from Osteopathic, which has since closed, say she had probably been unconscious for as long as 45 minutes before measures were taken to revive her.

Fenton’s prison psychiatrist, William Pederson, told Guthrie the inmate had threatened suicide two days before she was found. If the threat was true, Guthrie said, “then why wasn’t she on suicide watch?” According to Guthrie and the prison system’s own rules on suicide threats, Fenton should have been placed in a glass-enclosed room with no sheets and under 24-hour surveillance. “She was not. She was found alone in a single room on the psychiatric floor. There was no one watching her. ... We were called to [that floor] because we were told it was a suicide by hanging. ... She wasn’t hanging, but there was a sheet wrapped around her neck.”

The Tarrant County Medical Examiner’s report ruled her death a suicide based primarily on the prison hospital authorities’ account of events, but her family obtained an independent autopsy report that says her neck injuries are consistent with her having been placed in a choke hold. They have filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the bureau and called on the FBI to investigate,

The charge that Guthrie was asked to change the response times on his report is being hailed by her family and attorneys as proof that something very bad happened that day that the prison is trying to cover up. Any way you look at it, Guthrie said, whether it was suicide or, as her family believes, she was killed by others, deliberately or by accident, “Fenton’s death occurred because of Carswell’s neglect and incompetence and the prison is trying to cover that fact up.

“It was a ‘sentinel event’ in every definition of such a thing,” Guthrie said, “but at Carswell, it never even happened.”

You can reach Betty Brink at

bcbrink@sbcglobal.net.

Email this Article...

Email this Article...