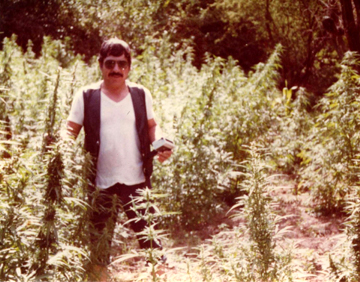

Hooks, in one of the Quintero clan’s marijuana fields, shared with corrupt Mexican federal agents.

Hooks, in one of the Quintero clan’s marijuana fields, shared with corrupt Mexican federal agents.

|

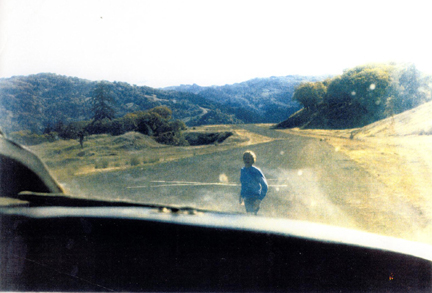

One of Hooks’ several airstrips in Mexico. He moved operations from strip to strip to avoid problems.

One of Hooks’ several airstrips in Mexico. He moved operations from strip to strip to avoid problems.

|

Miguel Caro-Quintero, left, with Michael Hooks, second from right, at Hooks’ wedding one week after the kidnapping of Kiki Camarena.

Miguel Caro-Quintero, left, with Michael Hooks, second from right, at Hooks’ wedding one week after the kidnapping of Kiki Camarena.

|

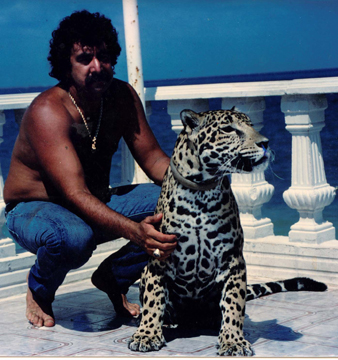

Hooks with Tequila, a Mexican jaguar. He’d hoped to open a zoo, but the animals were confiscated after his 1987 arrest.

Hooks with Tequila, a Mexican jaguar. He’d hoped to open a zoo, but the animals were confiscated after his 1987 arrest.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Smuggler’s Run

The U.S. government put his name on the street and his life on the line.

By PETER GORMAN

The tall, slim man sitting in the Texas living room, telling stories in a rich baritone, bottled water in hand, looked and sounded more like an actor than a drug smuggler. In a brown sweater and khaki pants, with a watch as his only jewelry, he certainly didn’t look like either the multi-millionaire he once was or the janitor he’s been occasionally since the millions disappeared.

Dark, deep-set eyes were perhaps the feature that gave the most accurate hint of the 53-year-old’s story and his circumstance — one of the biggest pot smugglers of all time, now a fugitive, not from the law but from what Michael Hooks says the law has done to him: broken all its promises and left him exposed to the vengeance of Mexican drug baron Miguel Caro-Quintero.

Most Americans have never heard of Michael Hooks, but many have heard of Caro-Quintero, one of the biggest drug lords in history and a man whom Hooks helped put in jail, albeit in Mexico. Miguel’s older brother Rafael is serving time for the kidnapping, extended torture, and murder of DEA agent Enrique “Kiki” Camarena in 1985. Miguel is doing time for a sting Hooks set up with the Drug Enforcement Administration. Both the Caro-Quinteros are, by all accounts, continuing to run their drug empire from their not-so-spartan cells, writing another twisted chapter in the bizarre saga of this country’s war on drugs.

Hooks’ story is bound up with that of the Caro-Quinteros and Camarena — tied up with the money, machinations, and violence of the drugocracy that rules in parts of Mexico and this country and with the drug cops who have spent so many years fighting the drug barons, while the rivers of pot and cocaine and heroin — and now methamphetamines — have continued to flow north around them, to meet the never-ending American demand.

The place was called El Bufalo, and it was legendary in pot circles in the 1980s, though most thought it was indeed legend and not fact: a Chihuahuan marijuana empire of 13 pot farms of 500 to 1,200 acres each, cultivated with tractors and the best in agricultural technology, employing thousands of people and producing tons and tons of weed that got shipped out via dozens of planes on multiple airstrips. But Hooks saw El Bufalo, knew it to be real. In fact, he ran much of it.

For Hooks, the road to El Bufalo ran through the U.S. Marine Corps, which introduced him to the joys of smoking marijuana, inadvertently showed him how to smuggle it, and provided him with buddies who helped get him started in the business.

A Florida native who grew up in Alabama, son of a Navy man, Hooks joined the Marines the week he graduated from high school. It was the height of the Vietnam war, and Hooks trained as a radar and missile electronics technician. He never went to ’Nam, though — instead, he and his unit were sent to the Mexican border to take part in Operation Grasshopper, an action intended to stem the flow of marijuana coming into the United States by tightening the loopholes in the radar systems all along the border.

“If you ever want to make a smuggler out of someone, teach them all the places where radar can’t detect movement,” Hooks said with a laugh, “I was taught every blind spot on the border.”

When he got out of the Marines in ’73, Hooks almost immediately started selling small amounts of marijuana. That quickly earned him a small prison term — three years, after he was busted in North Carolina with intent to distribute a pound of it. Three months into his sentence, he was moved to a prison cattle farm to work.

Hooks might have done his time and gone on to some other way of life. But 16 months after he got to the work farm, President Gerald Ford handed Richard Nixon a pardon for his Watergate-related crimes. “Well, that really pissed me off,” Hooks said. “I’m doing time for pot, and he’s let off the hook. So I decided to take off.”

For hours, he ran through swamps, slogging through the water to keep the dogs and prison guards off his scent. At dusk he hit an old farm road and got picked up by someone who took him to a nearby freeway. From there, with the help of family and friends, he made his way home to Alabama and then set off hitchhiking to California. There he met up with some Marine buddies with connections to big pot suppliers in Mexico. For a while, Hooks helped run the drug back east to Alabama and North Carolina. After a few months, he made his way further up the food chain and started smuggling it over the U.S.-Mexico border. It was, he said, surprisingly easy.

His pot career took another uptick shortly thereafter, when a buyer put Hooks in contact with two dealers from Alabama who’d recently lost their supplier and were looking for a new one. One of the two dealers flew into the Los Angeles airport, handed Hooks a briefcase, and disappeared. Inside was $25,000, a 50 percent down payment on 500 pounds of pot.

Hooks was hooked. When the first shipment, stowed in a hidden compartment he’d built into the camper shell on a pickup, arrived without a hitch, the two Alabama dealers invited Hooks in as a partner; they wanted as much weed as Hooks could get them. A relative who didn’t object to Hooks’ dealing, as long as it was only pot, helped him build several compartments in an RV, enough to hold nearly 1,000 pounds of product. Soon he needed a second trailer, and he and another driver were making two or three trips every couple of weeks. “We started rolling in the dough,” Hooks said.

In a year and a half, Hooks estimated, he made about $4 million. He bought a horse ranch outside San Diego and other real estate and started racing thoroughbreds. Then, feeling he was getting the short end of the deal with his Alabama partners, Hooks went out on his own — and, six months later, back to jail. This time it was much worse, however: This jail was in Mexico.

He was moving a load at night through the desert, five men in two vehicles, and got stopped at a checkpoint near Tijuana. The federales got suspicious when the second driver had a little coke on him, and they searched the vehicles and found the marijuana.

“I paid a judge $50,000 to cut the others loose and took the heat,” Hooks said. “One of them was my brother, and if I didn’t, my parents would have killed me.” He was found guilty of trafficking and sentenced to a little over six years at the notorious La Mesa prison in Tijuana, where money bought small private homes, women, drugs, and anything else a person might want (except freedom). A lack of it meant one bowl of soup daily and sleeping on the concrete floor with no blanket. Hooks had money and got himself a little house.

He also got some respect for not bringing anyone down with him, and not long after he began his sentence he was approached by four American prisoners. They told him they were building an escape tunnel and asked if he wanted in.

“At first I turned them down,” he said, “but I soon changed my mind. La Mesa wasn’t fit for a human being to live in.” His job was to get rid of the dirt. Eventually, he found a solution that would work only in a Mexican prison: He rented a prison storage shack and filled it with the diggings. When the men made their break, they were seen immediately. They scattered, and three were caught. Hooks made it to the border and found a phone, and his girlfriend came to bring him back across to the U.S.

The prison break brought television exposure — not something a smuggler wants — so Hooks sold his horse ranch, moved to Tucson, and took a year off to let things cool down. When he started up again, he switched from the low-grade marijuana bricks to high-grade sinsemilla — seedless pot that’s considerably stronger. That allowed him to make good money with far less quantity — 40-kilo loads brought over in pickup trucks with campers. The profit was huge: “I was buying it at $100 a kilo and selling it for over $2,000.”

Hooks got arrested again a year later in Lukeville, Ariz., but luck smiled on him when the computers were down and his fingerprints couldn’t be sent nationwide. A judge released him the next day on a $50,000 bond. Needless to say, he ran, abandoning that trucked-in operation. Instead, he hooked up with one of his old Alabama partners and bought a plane. “We went to Puerto Vallarta and bought a little twin-engine Beechcraft, and I started bringing out about 900 pounds of sinsemilla every couple of weeks,” Hooks said. “We’d fly it up to Sonora, then take it into the States a piece at a time.”

On one of those trips in late 1982, a friend told him about some huge marijuana fields in the hills, so large they were cultivated with tractors and protected by the government. It turned out to be the Caro-Quintero clan’s operation, and it would change Hooks’ life.

The Caro-Quintero’s business then included dozens of family members, anchored by a low-key uncle, JuanJo, and his nephews Rafael and Miguel, the latter a 19-year-old six-footer with movie-star good looks. Hooks got an introduction — and an offer to move some of their product. He made a deal for 500 kilos of the Quintero pot, and with his Alabama partner’s help, sold it in three days. “Miguel Caro-Quintero liked that. And the next thing you knew we were doing it regular, and it just started to snowball,” he said.

Hooks was in his 30s by then, an experienced smuggler who knew the border from Baja to southeast Texas, with a partner who could move as many tons as he could bring out. He figured that the time he’d spent in jail was a fair trade for what the drug business was buying him.

“The money was there, the adrenalin rush was there, and that lasted for years at a time,” Hooks recalled. “And it was just pot. I didn’t think there was anything wrong with it then, and I don’t now. People dream of doing what I did, and I lived that dream.”

By May 1983, less than a year after he hooked up with the Caro-Quinteros, Hooks estimates he’d brought 25 tons out of Mexico. Pilots and airplanes “were coming out of the woodwork to work with us,” he said.

In late June of that year, Miguel told Hooks he wanted to show him something. “He drove me up to these gates with armed guards, and we drove past them to a clearing where there were maybe 80 acres of pot under cultivation. People had tractors, a diesel pump was putting water out from wells. I’d never seen anything so large.”

What he was looking at was one of a dozen fields, each 40 to 100 acres, just outside of Caborca, in Sonora, the base of operations for the Caro-Quinteros. It was an extraordinary sign of the faith that Miguel placed in him: Up until then, he’d always made his pickups at barns and warehouses far from where the pot was grown. He mentioned to Miguel that the plants were growing too close together, and the next thing he knew, Rafael — whom the DEA dubbed the “Mexican Rhinestone Cowboy” for all the jewelry he wore — had put him in charge of growing the pot. “I’d learned how to do it on my horse ranch after reading dope magazines and grow books, so I explain to the growers ... how to space the plants, how to pinch the branches so they’d split, how to prune the branches we didn’t want. I got some resistance at first, but I had their trust because I was moving more product than anyone else.”

By 1984, the clan had moved its fields to El Bufalo in Chihuahua and expanded them considerably. Hooks expanded with them: He bought a number of ranches, totaling about 150,000 acres, built six airstrips, and bought 27 more planes. “We were running six or seven planes at a time, and when we weren’t doing that, I was inspecting fields or fixing problems with the other planes. It was 24/7, non-stop, with that large a system,” he remembered. “Other smugglers were bringing in 8 to 10 tons by ship from Asia once a month, but I was doing 50 tons a month for those two years. Heck, the first 50 tons from the pot I helped grow I got rid of in nine days.”

It sounds like boasting, but a Drug Enforcement Administration chart of Hooks’ organization, put together around that time, bears him out. It lists 28 planes, 14 pilots, seven flight crew, and 20 ground crew on Hooks’ end; 33 commercial properties and stash houses in Tucson, and more than 40 distributors. And those were just the U.S. people.

The scope of the operation, once it moved to El Bufalo, was almost unimaginable, Hooks said — the factual basis for the legend that grew up over the next few years. “In ’84, when they moved the fields, there were 18 trucks moving the buds — the smokable flowers of the marijuana plants — when we harvested. There were acres of buds drying in the sun and then tar-paper sheds maybe 40 yards long, and they’d be full. There were maybe 3,000 people in the area working on it, from the growers to the cutters to the women making the food for the workers. There were three one-ton cattle trucks a day just carrying tortillas out to the workers.”

Like the Brooklyn and Jersey Mafias before them and the Cali and Medellin cartels after them, the Caro-Quinteros knew the value of taking care of their own. The family paved the streets of Caborca and put in electricity. They built churches and gave to the schools.

“They lived high and spent a lot of money on themselves and drove around in tricked-out Grand Marquis,” said Hooks, “but they were good to everybody in the community, and the community loved them. The Mexican government loved them. They were bringing in billions in U.S. currency, and not only was it helping to stabilize the peso, everybody was getting a piece — politicians, the DFS — the equivalent to our CIA, federal police.”

Hooks estimates that he probably made $50 million in those two years. He bought ranches, planes, bulldozers. He sent money north to buy property in the U.S. He had hundreds of workers.

He laughed about a deal that got him one of his biggest ranches. “Me and a couple of buddies were drinking, and this fellow came up and said he had this ranch he had to sell. It’s got 500 cattle on it. So we did the deal, and then I turned to another guy and traded him the cattle for another ranch. That’s how it was in those days.”

There were lavish parties where Hooks flew planeloads of friends in from the States; everybody wore the best Rolexes, he built several homes, and he had women whenever he wanted. His family was taken care of. It was, he said, a dream.

Hooks said he believes the U.S. government knew about the El Bufalo operation but probably didn’t know the extent of it. It wasn’t unusual to see AWACs — radar-equipped military surveillance planes — flying overhead at his ranches, but by constantly switching landing strips, airplanes, and routes, he never lost a single plane. “These guys were just so well protected,” he said. “And so was I. I always had a DFS agent with me. Everybody knew who I was, but we were the good guys down there, the people bringing in U.S. dollars.”

From Hooks’ point of view it was a good world. Despite the money, violence was minimal. At the time, the U.S. government considered the Caro-Quinteros to be the least violent of the cartels, and Hooks said that despite everyone wearing guns, he never saw any shooting. Nothing in his criminal record suggests he was ever involved in violence.

Then came the first sign of a chink in the cartel’s armor: In the summer of 1984, one of the smaller fields got busted and 36 workers taken in. The workers were released three days later with no charges filed against them, and very little marijuana was confiscated — but it seemed the Caro-Quinteros and their associates were no longer inviolate. The problem seemed to be a DEA agent named Enrique Camarena.

It was the first time Hooks had heard the DEA agent’s name. “Miguel said someone high up in the government told his brother [about Camarena] and apologized for the disturbance. You see, wherever there was a [Caro-Quintero] field, the Mexican government had a no-fly zone, and only a DEA cowboy would ignore that.”

Camarena had seen more than one little field. He’d taken pictures of all of the fields in Chihuahua and brought them back to his superiors, who began pressuring the Mexican government to take action.

On Nov. 6, 1984, “I was in Caborca getting my bulldozer to make a new airstrip in Chihuahua when I got a call from Miguel telling me the gringos had come and that we had problems,” said Hooks. “The next thing you know, it’s all over the television with the DEA saying they got 8,000 tons” of marijuana.

The figure, Hooks said, was bullshit. “There might have been that much there,” he said, “but some was still growing, some was drying, some was being cleaned.” And, he said, “a couple of weeks later we got at least 100 tons of it back, because I moved that much of it myself between December and January.”

Whatever the actual figure, it was, and remains, among the biggest pot busts in history. And it meant that Camarena posed a real threat to the cartel.

Three months later, on Feb. 7, 1985, Camarena and his Mexican reconnaissance pilot, Alfredo Zavala Avelar, were kidnapped in Guadalajara. Camarena had just left the DEA offices in the U.S. consulate, on the way to meet his wife for lunch. When he didn’t show, Camarena’s wife contacted U.S. Ambassador John Gavin, who in turn called Mexican authorities. When they weren’t quick to respond, the United States initiated Operation Camarena, stopping and searching every vehicle coming from Mexico, turning the border into a 2,000-mile nightmare.

Hooks later told the DEA that he knew only a little about the missing agent. Shortly after the kidnapping, he said, Rafael called a meeting with him and asked Hooks if he knew a DEA agent named Camarena. Hooks says he told Rafael he didn’t, and that Rafael said that was OK, because ‘he’s been taken care of.’”

On March 6, someone tipped authorities that the bodies of Camarena and Zavala could be found on a roadside 60 miles south of Guadalajara. The pair had been tortured, buried, then their bodies dug up and moved.

Not long after, a copy of an audiotape was delivered to the DEA. It was a tape of Camarena being tortured for nine hours; not surprisingly, those who’ve heard it say it is unbearable to listen to. The DEA responded with Operation Leyenda — Operation Legend, the largest manhunt in DEA history.

Camarena had disappeared just days before Hooks married Diana, a California woman he’d known for years. At the wedding, Miguel Caro-Quintero was his best man. Hooks and his new wife flew to Cancun, where he bought a condo and laid low, in the face of mounting heat. Still, the lure of money and adventure was impossible to resist, and six months later, after making a deal with the local Cancun federales and their commandante to act as his protection, he was back in the game.

But things weren’t the same. With Operation Leyenda, anyone and everyone connected to the Mexican drug trade, and particularly to the Caro-Quinteros, was fair game to U.S. authorities. The big fields of El Bufalo were gone, confiscated by the government and turned over to the former workers after all of the pot was burned and the machinery removed. Rafael had been arrested in Costa Rica not long after Camarena’s body was found. He was brought back to Mexico, where he was convicted of the killing and sentenced to more than 100 years in prison. And many of the people the Caro-Quinteros had paid for protection were being fired or arrested; people still part of the operation either paid for their own protection, like Hooks, or lived without it.

By that time, however, even paying for protection didn’t guarantee it, and when the commandante on Hooks’ payroll got transferred suddenly, his replacement had the smuggler arrested — not so much for drug dealing as for not having paid off the new man. “I told him I was waiting for an introduction,” Hooks said.

It was too late for that, he was told: He was being shipped home the following day. “Hell, I couldn’t go back there. They had me on continuing criminal enterprise, breaking out of prison, all sorts of things. I’d have done 20 years to life in the U.S.”

The commandante said there was nothing at that time to hold him on in Mexico, but that if maybe he had some drugs they wouldn’t send him back. Hooks made a call — someone would plant drugs on his boat.

The next day, Hooks’ boat was searched, and a little marijuana and a few grams of cocaine were quickly discovered. The commandante announced that Hooks would be charged for the drugs in Mexico rather than being shipped back to the U.S. Hooks paid him $40,000 for the favor.

Despite the payoff, Hooks said, he was brought to a holding cell at the Interpol office where he was put in isolation — except for interrogations — over the next eight days, during which he was beaten regularly. “They kept wanting me to talk about Miguel, but I wouldn’t say anything about him. I admitted knowing Rafael — heck, he was already doing over 100 years, so I couldn’t hurt him — and I admitted moving pot, but I never admitted even knowing Miguel.”

He was finally brought to the maximum security wing of a federal prison in Mexico City. In 1987, he was tried and sentenced to 25 years. He appealed twice during the next four years and finally got his sentence reduced to just over 16 years. He spent about a million in payoffs during the appeals, he said, and spent additional money to make the prison bearable: He bought three cells and had a kitchen put in one of them and a bedroom in another. His wife, who’d had one baby in Cancun and another shortly after his arrest, had their third as a result of a conjugal visit. But by the end of the second appeal, she’d gone home to California. “It was still maximum security, and it was just too much for her to take.”

He began to hear that, on the outside, Miguel was taking the ranches that belonged to Hooks, on the pretext of money owed to him. Hooks said he verified the rumors — his condo in Cancun had been put in Miguel’s name and completely remodeled — and began to get furious.

“I’m in prison because I wouldn’t give this guy up, and he’s out there and he’s lost some loads and needs some funds, so he decides to get it from me. His justification was that I’d never have had all that if not for him.

“Well, I thought he’d never have had what he had without me. We complemented each other. But I wasn’t going to stay in prison 10 to 12 more years and get out to find the $4 million I had in property had all disappeared. I wanted him to go to prison and see what it was like to have somebody fucking you over and there’s nothing you can do about it. So I told my wife to call the U.S. attorney’s office and tell them that I’d tell them what I knew about the Camarena killing.”

So in 1992, Hooks told the DEA about the meeting with Rafael Caro-Quintero, at which Rafael had said Camarena had “been taken care of.” That’s all he knew, Hooks said. It wasn’t much, considering that Rafael had already been convicted of the killing, but it was enough to get Hooks included in a prisoner exchange that sent him to a federal pen in Tucson. Shortly after he got there, a deal was struck to give Hooks light sentences — a total of about five and a half years — on his organized crime and prison escape charges in exchange for working with the DEA to try to lure Miguel Caro-Quintero to a country from which he could be extradited to the United States.

The DEA’s idea was a sting. Documents that Hooks provided show that he first called Miguel from prison in 1997 to set up a deal by which Miguel would deliver 3,000 pounds of pot to a friend, actually an undercover DEA agent. The phone calls were audiotaped on Miguel’s end and video- and audiotaped on Hooks’ end. The pot was delivered to the agent in Tucson, the Caro-Quintero stronghold in the U.S., giving the federal prosecutors something Miguel wouldn’t be able to wriggle out of, should he ever be arrested.

The deal also established trust between the undercover agent and Miguel, which was vital to ensnaring him. Hooks again called Miguel and vouched for the undercover agent, this time telling him that the agent had a good connection for cocaine in Colombia, but that he could fly it only as far north as El Salvador. Would Miguel take the loads from El Salvador into Mexico and then on to Tucson?

The DEA was hoping that Miguel, interested in meeting his new “partners,” would come to El Salvador for the first shipment. A deal had already been worked out between El Salvador and the U.S. to extradite Miguel if he stepped onto Salvadoran soil. However, Miguel sent someone in his place.

Hooks, meanwhile, had served his five-plus years and was released to a halfway house in late 1997. Including his time in Mexico he’d served just over 10 years for the Cancun bust. His wife had divorced him and remarried. He re-entered the regular world as a $6.50-an-hour night janitor, then moved through a series of unmemorable jobs, keeping his head down and his profile low.

It was another two years before Hooks heard from federal prosecutors again. In 1999, he says, they called to ask if he would help with Miguel’s extradition, should he ever be arrested. Hooks told them he’d do it for $3 million — about what he said Miguel had stolen from him. Hooks didn’t hear back from the feds until 2001.

Federal prosecutors and State Department officials have declined to discuss Hooks’ cooperation or the case against Caro-Quintero. But Hooks’ meticulous collection of records — provided to Fort Worth Weekly — verify his cooperation and their promises.

Still trying to figure out a way to extradite Miguel, the prosecutors were looking once again at the 3,000-pounds case — apparently the only one that the Mexican government would agree to extradite him on. This time, Hooks said, prosecutors told him they couldn’t offer him the $3 million he’d asked for, but if he helped with Miguel’s arrest and extradition he’d be eligible to collect the reward of up to $5 million the U.S government had offered for the drug baron. The government also promised that his identity would be kept strictly confidential

In December 2001, Miguel was arrested in Sinaloa, Mexico, on a warrant based on the case Hooks had helped make against him. However, instead of the $5 million reward, the feds offered Hooks $300,000, plus another $200,000 should Miguel be extradited and if Hooks testified at trial. Hooks told them that if he wasn’t going to get the reward he wanted no part of it. “That wasn’t enough money to have me go into hiding from the Caro-Quintero clan for the rest of my life,” he said. “I didn’t want to have to give up my kids.”

Unknown to Hooks, within hours of Miguel’s arrest, the Mexican government announced at a press conference that Hooks was responsible for making the case, and every major Mexican daily newspaper mentioned his name. In February 2002, he discovered that he’d been a walking dead man for two months; that’s when he was notified that the federal government had sent a request for extradition for Caro-Quintero with Hooks’ name on the affidavit.

“Two days later I was out of Tucson and have not been back since,” he said.

Hooks was not the only one astounded that the government would put him in that jeopardy. Assistant U.S. Attorney Jim Lacey removed himself from Hooks’ case over the incident. In a letter to his superiors he called the breach of confidentiality “unethical, immoral, and illegal.”

As soon as he heard of his cover being blown, Hooks called the top DEA agent in Tucson. The agent said the best he could do was offer Hooks $8,500 a month — not exactly pocket change — until Hooks, the DEA, and the State Department reached an agreement. Hooks took the money and went on the run. “I couldn’t stay in Tucson,” he said. “I was a dead man if I stayed there. I feel lucky I wasn’t hit during the two months my name was out there.”

A month later the DEA contacted Hooks and made the same offer as before:$300,000 in cash and another $200,000 if Miguel were extradited and convicted. Hooks said he’d agree only if it was put into writing that he could apply for the $5 million reward. The agents gave him the agreement; Hooks signed, collected, and got the hell out of Dodge.

For the last four years, Hooks has been on the run, fearful that if he visits his family or stays too long in one place, Caro-Quintero’s vengeance will find him.

He’s convinced that his name was leaked to the Mexican government in December 2001 by American officials — possibly by a woman now in the top echelons of the DEA, who was in charge of the case back then.

Defense attorneys who’ve tangled with the DEA say they have no problem believing that Hooks’ confidentiality was blown by federal agents or prosecutors.

“I had a case one time where a person in the witness protection program was exposed when he got into a spat with the government over payment of a dental bill,” said a prominent Virginia defense lawyer. “So getting even with a guy even vaguely connected with the Camarena killing could certainly provoke the feds to release his name. You know — payback.”

Another attorney said the high-level administrator Hooks blames in his case has done the same thing to others in the past.

Celerino Castillo, a friend of Camarena’s and a former DEA agent in Guatemala, told the Weekly that the DEA has a reputation for burning its snitches. “That’s what they do. They figure you were a drug-dealing scum, and now you’re a snitch as well, so they like to burn you after they’ve squeezed you.”

That characterization is backed up by Terry Nelson, who served in the U.S. Coast Guard, Border Patrol, and U.S. Customs in Central and South America in a law enforcement career that spanned 30 years. DEA bosses “would burn their friggin’ mothers to get an arrest,” he said. “That was their reputation, and it was earned: I had a lot of [snitches] say they wouldn’t deal with the DEA exactly for that reason.”

Hooks has tried to apply for the $5 million reward, but he said no one from the State Department or DEA will respond.

He surfaced in North Texas recently and agreed to an interview with a reporter he’d known years before. “I was left to hang out and dry,” he said. “I hope I’ll get the reward some day, but if I don’t, I don’t. But I still hope I can help educate the American public to the fact that the U.S. government does not keep its promises. I’d hate to see someone else in my position.”

As for Miguel Caro-Quintero, he may never be extradited. According to the DEA, he and his brother Rafael continue to run their organization from the relative comfort of the Matamoros prison where they are serving time, and his political influence is still strong. And if that’s the case, he certainly has the power to reach out and eliminate Hooks if he knew where to find him.

Running for the rest of his life obviously wasn’t what Hooks had in mind as a retirement plan. Smuggling is a young man’s game, and he’d planned on getting out of it long ago, maybe — of all things — running a zoo in Cancun with his wife and kids.

So did the good times outweigh the bad in a smuggler’s life? It seems that, if it balanced out for anyone, it should have for Hooks, whom Keith Stroup, founder and president of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws, calls “one of the biggest, and maybe the biggest pot smuggler of them all.”

For a long time, Hooks said, he was convinced that it did: The money and the adventure were fantastic, and he still believes there was nothing wrong in smuggling pot.

“But these last years, being on the run? That’s like being in prison still. I get by with a fake name. I can’t have relationships. I can’t get a real job.” He does day work to feed himself.

“I can never see my kids, and I hardly talk with them,” he said. “I can’t take a chance that Miguel would try to get to me through them.

“So if the question is was it worth it, the answer is no.”

Email this Article...

Email this Article...