Makeig was a Star-Telegram reporter in 1973 when this photo was taken. (Courtesy of Martha Davis)

Makeig was a Star-Telegram reporter in 1973 when this photo was taken. (Courtesy of Martha Davis)

|

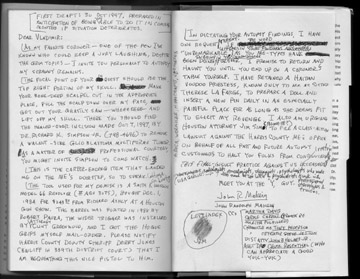

Carl Daniel found the suicide note written in the back of a Kinky Friedman novel. (Courtesy Carl Daniel)

Carl Daniel found the suicide note written in the back of a Kinky Friedman novel. (Courtesy Carl Daniel)

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Postscript from a Strange Land

John Makeig’s life and death were as bizarre as anything he ever reported. And that’s saying something.

By DAN MALONE

The mystery Carl Daniel was reading had a surprise ending, but it wasn’t one the author wrote.

On two blank pages at the end of the book was what appeared to be a handwritten suicide note. It was addressed to a coroner named Vladimir, described the gun the writer planned to use to kill himself, and mentioned a curse from a voodoo priestess. The note was signed and bore an inked print of the man’s left index finger.

“At first, I thought it was a joke,’’ Daniel said. “I thought it was an exercise. It started getting funnier and creepier, and I saw the fingerprint and the signature and went ‘Wow, this is the real thing.’”

Daniel went to his computer and Googled the name of the man who signed the strange note. Sure enough, he was dead. Another click or two revealed that he had been a newspaper reporter who had worked years ago for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram and the Houston Chronicle. So he called me.

Daniel, an old friend of mine in Dallas, wanted to find out what I might know about the dead man. I recognized the byline but didn’t personally know the man or anything about his death. Intrigued, I started doing the things that reporters do when they hear a curious tale. I learned that the dead guy was more than a little odd — he hoarded cigarette lighters, obsessed about possible alien abductions, and had kept a joint tucked in the lining of his tie. I found out that he was a kind-hearted loner, a quick wit, and a gifted writer with a knack for stories as quirky as his own life. And I discovered that that during his 58 years on the planet, his life intersected in strange ways, at least on paper, with the lives of some other very interesting people — a man who wants to be the next Texas governor, a nationally known prosecutor, an internationally famous musician, and a cast of characters that might have leapt from the pages of their own twisted novel. A man who thought he could fly. Another who had sex with a horse. A short murder defendant who demanded a jury of diminutive peers.

Doug Clarke pronounces the name with a pause between the first and middle, the middle and the last. His mind rewinds to events decades old.

More information: “John Randolph Makeig, whom I considered a pretty good friend, was absolutely the weirdest guy I’ve ever known in my life,’’ said Clarke. Now a TCU journalism instructor, Clarke was one of Makeig’s editors at the Star-Telegram in the early 1970s. Makeig, who covered police and the courts for the paper, had a tendency “to go off on tangents.’’ Lots of tangents.

He was an accident-prone driver who once tried to persuade his editors that an exceptionally long story he had written — Clarke remembers it being 43 pages long — about a routine fender-bender was the best story of his career and deserved a Pulitzer Prize. It was whittled down to a three-inch brief and buried inside the paper.

Makeig was obsessed with the possibility that a rash of suspect cattle mutilations might be the handiwork of space aliens. When his editors urged him to steer clear of the livestock abduction stories and stick to news on the night police beat, he continued to chase down strange theories during the day. “He went around the corner and off the screen on some of that,” Clarke recalled.

He had an “insane interest’’ in a perennial political candidate who made his living as a woodchopper — and couldn’t understand why his editors weren’t equally fascinated by the quirky character. “One of his problems was he thought [the woodchopper] was a perfectly normal guy,’’ Clarke recalled. “He didn’t know what unusual or weird was because his view of the world was so skewed itself.’’

A wiry man who wore wire-rim glasses and a trench coat, Makeig kept meticulous records of his work and could retrieve facts from reporter notebooks filled with his observations from years or decades earlier. A room he rented in a friend’s house in Fort Worth was filled with cans and boxes containing the yellowing clips of every word he had written for the Star-Telegram. The walls were stained brown from his two-and-a-half pack-a-day cigarette addiction. On his bed, a pile of books and papers left a clearing just large enough for his compact frame. A lifelong bachelor with the habits thereof, he once confided to an editor that he had purchased a brown bedspread “so he didn’t have to wash it very much, or at all.’’

Like many journalists, he was, for a time, a heavy drinker. But even those who mention his drinking and who recall some of the “whiskey bumps” in the paint jobs of the cars he drove, said they don’t remember seeing him snockered. He also smoked a good deal of dope. Evan Moore, who worked with Makeig at both the Star-Telegram and later at the Houston Chronicle, remembers complaining to Makeig about the smell of marijuana lingering in the small press office the two men shared at the Fort Worth police station. “Sometimes you’d find the damn joint,’’ Moore recalled. “I’d say, ‘John, you’ve got to quit blowing weed down there.’” Several other friends from that era remembered the emergency joint he frequently hid in his tie.

He was a generous mentor to young reporters. Mark Nelson, a Washington communications consultant who learned the ropes of the cop shop from Makeig in the 1970s, marveled at the number of cops, coroners, ambulance drivers, lawyers, and jailers Makeig knew. “Can I possibly learn as much as this guys knows?’’ Nelson remembered thinking. “Can I possibly know as many people as this guy knows? He was clearly in his element.’’

Another former colleague remembered that Makeig collected photographs of homeless people he encountered in downtown Fort Worth. “He did what he called the ‘one-dollar faces,’” said Jim Pinkerton, a writer for the Chronicle who knew Makeig when they both worked in Fort Worth. He paid his subjects a dollar each to sign photo releases. “He put them together in a photo exhibition. I think he got it published,’’ Pinkerton said.

When he dated, acquaintances said, the women were often quite beautiful. But he seemed to keep his distance from friends and dates alike. If his eccentricities were well known, other facets of his life remained mysterious. “I would say nobody knew John very well,’’ said Ron Hutcheson, a former Star-Telegram reporter who now covers the White House for the Knight-Ridder chain, which includes the Fort Worth daily. “His dark side was apparent. He loved the dark milieu of the cop shop and the criminal courthouse. It was his world, and he thrived on it.’’

Hutcheson, like some of Makeig’s other friends, sometimes wondered what it was that Makeig found so fascinating about the world he covered. “I always had this feeling that he had a separate underground life,’’ Hutcheson said, “ and somehow there were lots of guns involved.’’

Makeig left the Star-Telegram in the early 1980s for a job as a reporter for the Houston Chronicle, where he worked until the late 1990s. As he had in Fort Worth, he gravitated to the world of criminals, lawyers, and courtrooms. He became a fixture at the Harris County courthouse where he developed an eye for off-beat crime stories that he boiled down to their gritty, often humorous, essence.

One, a 1991 story about a mistrial in a child injury case, earned Makeig top honors for short feature from the Associated Press Managing Editors group. “Prosecution’s key figure threw tantrum, pacifier,’’ read the headline on the story about a teen-age baby-sitter accused of spanking a 2-year-old boy hard enough to leave bruises on his rump.

The victim was “such a little hellion that a lot of people — perhaps including jurors — were empathizing with the baby sitter,’’ Makeig wrote. “For three days, during jury selection and testimony, the 2-year-old screamed, yelled, and ran up and down the hallway’’ outside the courtroom. “When it came time for the child to be shown to the jury, he threw a tantrum in his father’s arms. That scene ended with the boy throwing his pacifier 20 or 30 feet across the room.’’

An earlier brief, headlined “Unbridled passion leads to sentence,’’ matter-of-factly recounted the ordeal of a 41-year-old man who let his love for a horse get the better of him. “A man caught having sex with a horse has been sentenced to 10 years probation and fined $10,000 for trying to kill its owner during a gun battle in which the female horse was killed,’’ Makeig wrote. The mare’s owner and her paramour exchanged gunfire, and one of them hit the horse accidentally.

“It was not determined,’’ he wrote “who killed the horse.’’

Yet another story recounted how a 32-year-old paranoid-schizophrenic avoided a murder trial for stabbing his 79-year-old grandmother to death. “A man once arrested for running nude down an airport runway because he believed he was an airliner in route to Egypt has been sent to a hospital pending his trial on charges of murdering his grandmother,’’ he wrote. Makeig said the man had a “mental history pre-dating his LSD-propelled venture down the runway at Houston Intercontinental Airport ... No one questions his mental aberrations, even the prosecutors who want to try him for imbedding a knife in [his grandmother’s’] eye during a dispute about placing a car cover over her car.’’

And then there was his story about a short murder defendant who demanded a jury of equally short peers. The 4-foot-6- inch defendant was seeking a form of “scaled-down justice.’’

Quirky news was only one of Makeig’s fortes, said Mary Moody, who edited Makeig at the Chronicle. “He was a master of that, although he was also a master of making very complicated stories very understandable.’’

He also collected weird names he encountered covering the news, in lists that still circulate in the Houston newsroom: an anesthesiologist named Gasser, a banker named Ernest Deal, the Boxwell funeral home, a burglar named Lawless, a man in a sex case named Orji, a prostitute named Flesher.

The lists were only one of the ways that the strange world he covered seeped into the equally strange world that was his private life. Makeig’s sister Martha Davis, a Houston writer, remembered how he meticulously prepped his freshly laundered suits for his profession by lining them up in his closet, then loading each with reporter’s notebooks and pens so “they were all ready to go’’ when news broke.

He inexplicably hoarded cans of lima beans and Bic lighters — “drawers and drawers’’ of them, Moody recalled. And he indeed had a thing for guns.

Several friends remember that he once tested a new gun in an apartment he was renting by firing into a stack of newspapers or phonebooks on the floor. The bullet tore through the pile. “He was really lucky he didn’t shoot someone,’’ Moody said. He trolled gun shows, swapped guns with people he met at the courthouse, had weapons he owned modified by gunsmiths.

Harris County District Attorney Chuck Rosenthal recalled that Makeig also possessed an equally lethal wardrobe. Before he was elected district attorney, Rosenthal was a felony prosecutor and sometimes ran “ugly tie contests” for people who passed through the courthouse. “Makeig always won,’’ he said.

Others remember Makeig as an exceptionally trustworthy journalist, one who could keep a secret locked away forever in his professional vault. Derry Jones, a former Harris Court courtroom bailiff, said Makeig was more trustworthy than most of the people he wrote about. “When you’re around crooks and criminals and egos, you meet a lot of people. He was honest and straight-forward and a man of his word, and that’s more than I can say for 99 percent of the people down there.’’

In the late 1990s, Makeig started having headaches and problems with his vision and balance. He confided to friends that he feared he had a brain tumor but put off seeing a doctor.

“One Saturday ... he called in sick. I ended up going out to his house,’’ said former Chronicle political writer John Williams. “He was stumbling and off-balance. I think he knew there was some kind of issue and just didn’t want to confront it.’’

When Makeig finally sought medical help, the bleak news confirmed his fear of a brain tumor. He underwent repeated surgeries, radiation implants, and steroid treatments, but the cancer continued to gain on him. “He fought it head-on and did the best he could,’’ said Williams. “He did it pretty damn stoically.’’

Makeig had no intention, however, of dwindling away in a hospice. He told his doctors that, when the time came, he had his own Rx for the damned tumor: “Smith & Wesson therapy.’’

The doctors took his gallows humor seriously. “They wanted to take him straight to the psych ward,’’ his sister recalled. She took it seriously as well — their mother had committed suicide, also with a gun. She told Makeig that when the time came she would not help him, but wouldn’t stand in his way either.

And so Makeig planned his death as methodically as others might plan a gala affair. A few weeks after his first surgery, he opened up a copy of Road Kill a whodunit by Kinky Friedman, the comedic musician turned novelist now running for Texas governor. On a blank page at the back, he began a draft of the suicide note he would later mail to a group of friends. He said he was writing “in anticipation of being unable to do it in coming months.’’

The note was at least as strange and funny as the place he chose to write it. The novel was one in a series that casts the author — a former country-and-western singer with a knack for twisted lyrics — as a private detective. In Road Kill, detective Friedman is attempting to prevent the murder of his friend, Willie Nelson, after a member of Nelson’s band is popped while touring.

Makeig’s note, like the novel, is threaded with the names of real-life people he encountered. He wanted Jones, the bailiff, to have the gun with which he planned to take his life. He instructed Vladimir the coroner — an apparent reference to former Harris County assistant medical examiner Vladimir Parungao — on how to autopsy “my scrawny remains.’’ He also threatened to haunt the coroner “until you end up on a coroner’s table yourself’’ if he lapsed into coroner lingo and described his corpse as “unremarkable.’’ “I have retained a Haitian Voodoo Priestess, known only to me as Sister Therese La Farge, to prepare a doll and insert a new pin daily in an especially painful place for as long as she deems fit to elicit my revenge,’’ Makeig wrote.

The note mixed fact and fiction — stating that a real life lawyer he knew, a man who used to work as a gunsmith, had made modifications to his Smith & Wesson Model 66. The lawyer told me that, while he did in fact know Makeig, he had never worked on any of his guns. As for the voodoo priestess, she appears to have been as fictional as any character in a novel.

Makeig inked the print of his left index finger beside his signature, then indicated he was copying the note to a group that included his sister, two Chronicle editors, and Harris County’s legendary former District Attorney John B. Holmes, Jr. His final words: “Meet you at the ‘Y’, guy.’’

The note was dated Oct. 30, 1997, three weeks after doctors removed a tumor the size of a walnut from his brain. But Makeig wasn’t ready — yet — to take his life.

During the next two years, Makeig underwent two more laser surgeries, a radiation implant, and steroid treatments. When he could, he continued to work at the Chronicle. When a second surgery in the fall of 1999 cost him the use of his left leg, he seemed to succumb.

Makeig composed another suicide note, a darker version of what he had written in the Friedman novel, explaining to his friends and acquaintances why he had decided to end his life. He pondered his remains and the mess that a death from gunfire leaves behind. He selected a site that he thought would inconvenience the fewest number of people — a tree outside the Harris County medical examiner’s office. He did not want friends or family, his sister explained, to “have to deal with the shock and surprise’’ of finding his body. People killed by cancer frequently aren’t autopsied, but Makeig knew that if he ate his gun, despite his grave condition, he would likely land under a coroner’s knife. He wanted to be “right there,’’ Davis said, “where he needed to be.’’

Makeig used to tell people he was the first baby born in Amarillo on New Year’s Day in 1942 — and was planning, with his trademark sense of the macabre, to be the first Houston death in 2000.

“That was his plan,’’ his sister recalled. “He went to the coroner’s, and on the way he passed by the main post office and put all these letters in there,’’ she said. “This was supposed to be his last word on the subject.’’

As the rest of the world rang in not just another new year but the uneasy dawn of a millennium colored with fear of terrorism, Makeig sat under a tree outside the coroner’s office, gun in hand, contemplating what was to be his final, solitary act. The moment came upon him. He let it pass.

When his sister’s phone rang the next morning, it was Makeig’s voice, not that of a police officer, she heard. “He called here around six in the morning and said, ‘I really made a mess here this time,’” she recalled. Though his reasons for wanting to take his life seemed clear, Makeig gave his sister no reason for deciding to live. “He did not [explain], and I didn’t ask.’’ Davis said she believes her brother mailed copies of his suicide note to dozens of friends. “Most people really took it to be a joke,’’ she said.

But Makeig felt he owed some an explanation for not pulling the trigger. Radford Sallee, another reporter friend, recalled, “John told me and some other friends that after putting his affairs in order, he drove over to Ben Taub Hospital, where the county morgue was housed, lay down on the grass, then couldn’t make himself pull the trigger. ... After a while he got up and went home. He felt very embarrassed.

“I feel sure that after he had become helpless and in great pain, he wished he had gone through with it,’’ Sallee said, “but I never recall him saying so.”

Makeig lingered for three more months, slowly fading from this world to the next as an infection festered in his brain. He died March 30, 2000, after 10 days in a hospice.

“When he actually died, it was [from] a massive infection in his brain. It was from his laser knife surgery where they implanted a little radium bead. When the tumor is killed, what happens is the tissue around it becomes necrotic itself,’’ his sister explained. “He was not in touch with the rest of us on this planet. It was an awful three months.’’

Makeig left his modest estate to his sister. “There was an awful lot of ammunition,’’ she said. “We donated that to the police department.’’ She found some Christmas ornaments from their childhood and their father’s clarinet.

She took his books — mostly paperbacks and light reading — to a Half Price Books store in Houston. The Friedman novel with the draft of her brother’s suicide note stayed on the shelf there until late last year, when Carl Daniel’s son, Paul, bought it as a gift.

The reason why Makeig chose the Friedman novel to record his darkest thoughts, like the reason he chose to keep fighting the cancer, went with him to the grave. It may simply have been a matter of convenience. Maybe, his sister said, “he finished the book and he was sitting in his chair and just didn’t want to get up and find anything to write on.’’

Or maybe it was something in the Friedman novel.

I wanted to ask Friedman about Makeig. Kinky had autographed but not inscribed the book. Maybe the two funny men knew each other. But spokesman Cleve Hattersley said “the Kinkster,’’ as he refers to himself, was busy raising money in Hollywood for his campaign for Texas governor. He might call back, Hattersley explained, he might not.

As things turned out, Friedman didn’t call. But who would expect a politician — even a Kinky one — to return a call from a reporter working on a story involving a voodoo curse, a corpse, and man who romanced a mare?

Email this Article...

Email this Article...