No one does Broadway – or pretty much anything – like choreographer Bruce Wood and his dancers.

No one does Broadway – or pretty much anything – like choreographer Bruce Wood and his dancers.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Kultur

Chopin, Wood, and Cole — the fine arts community is full of the elementals.

Not only is Bruce Wood a world-class contemporary ballet choreographer, he has that one intangible that most choreographers lack greatly — personality.

Wood is actually liked by his artistic partners at Bruce Wood Dance Company, his dancers, and the outsiders with whom he regularly works. In putting together BWDC’s most recent program in celebration of his 10th anniversary season, the company founder and director let the company select two ballets from his extensive repertory. The group chose 1998’s Being, a setting of the Bach Double Violin Concerto, and the four-year-old Chichester Psalms, a piece based on Leonard Bernstein’s setting of the biblical verses. “Psalms was a surprise choice,” Wood told Kultur before the performance. “It’s a toughie, with a lot of running around, but the dancers wanted to do it.”

Do it, they did — and wonderfully. Even though the ensemble betrayed some ragged, rusty edges in Being, the sparkling essence of the choreography came shining through. In what is hands (and feet) down one of Wood’s most joyous collaborations with a composer, the music and dance are propelled by logical and seemingly inevitable combinations that ring true at every beat. In Psalms, the movement is evocative of the maestro’s heartfelt score.

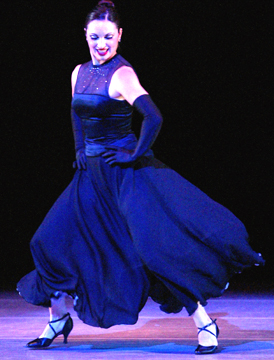

The program also featured a new work, Anything Goes, a montage of seven Cole Porter classics danced with irrepressible joy. Nobody does Broadway better than BWDC, and the audience responded rapturously.

BWDC’s next concert is at the end of April. What we’ll see, who knows: At the show last weekend, every program contained a voting ballot that listed the ballets in the company’s repertory. The two pieces that receive the most votes will be presented again.

The Big Red Scare

Whoever thinks Jumbotron-sized video screens are solely the province of stadium-rockers like U2 and The Rolling Stones should’ve swung by Bass Hall last week for pianist Vladimir Feltsman’s concert. The venue’s fancy new mammoth screen that hung over him provided more than big-show extravagance. Surprisingly, it also tempered the esoteric edges of the fiery Russian’s program by offering a close-up view of his fleet fingers at work. Instead of being “up there onstage,” good ol’ Vladimir was in your lap. The result was, um, oddly comforting.

The playing itself was provocative, strong, and deep. Beethoven’s Pathetique bristled with drama from the first crashing notes to the last, and the Chopin selections (three Polonaises along with the third Ballade) were mini-tone poems awash in longing and sorrow for the composer’s native Poland, reduced at the time to a Russian state. The little Mozart Piano Sonata in C Major, K. 330 was the only work that didn’t fare well, sounding tongue-tied and restrained. Otherwise, Feltsman’s piano sang throughout the evening.

Almost at the opposite end of the classical music spectrum, though no less entertaining, Bernstein’s hero Aaron Copland got a great work-out from the Fort Worth Symphony at Bass Hall last week, along with the Beethoven Second Symphony. Now as familiar in the concert hall as shameless knock-offs of his work are in Hollywood film scores, Copland remains our folk hero in tuxedo tails — in managing to synthesize church hymns, folk song, and various European influences, the Brooklynite devised an orchestral flavor often referred to as “the American sound.”

His Appalachian Spring is a jewel of American music and has few equals. Along the elegiac journey of the enlarged version of the famous ballet score, conductor Miguel Harth-Bedoya gracefully, sensitively paused to smell the roses. (Incidentally, Artur Rodzinski, father of Cliburn Foundation director Richard Rodzinski, led the first performance of Spring at a New York Philharmonic concert in Carnegie Hall in 1945.)

Harth-Bedoya was equally persuasive in his reading of Beethoven. Unlike an earlier look at the piece during the orchestra’s Beethoven Festival a couple of years ago, last week’s performance revealed a confident conductor not afraid to playfully shape details. Only the Copland Concerto, a work commissioned by legendary bandleader Benny Goodman in the 1940s and also performed here, didn’t take off. All this, despite clarinetist David Shifrin’s best efforts.

Where’s that Jumbotron when you need it?

Contact Kultur at kultur@fwweekly.com.

Email this Article...

Email this Article...