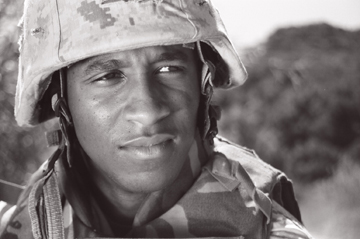

Watts (Pyro): ‘ It’s not a game over there.’

Watts (Pyro): ‘ It’s not a game over there.’

|

Tomlinson (Prophet): ‘The silence hits you, and you don’t know what you’re supposed to do with that.’

Tomlinson (Prophet): ‘The silence hits you, and you don’t know what you’re supposed to do with that.’

|

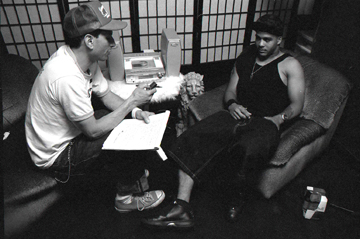

Spielman, with Marine Cpl. Anthony Hodge (Amp), about a month before Hodge returned to Iraq: ‘I said, “Just tell me your life story.”’

Spielman, with Marine Cpl. Anthony Hodge (Amp), about a month before Hodge returned to Iraq: ‘I said, “Just tell me your life story.”’

|

Rappers from the frontline aren’t likely to glorify the violence of war.

Rappers from the frontline aren’t likely to glorify the violence of war.

|

The 24 songs on Voices From the Frontline tell about the daily lives of men and women serving in Iraq.

The 24 songs on Voices From the Frontline tell about the daily lives of men and women serving in Iraq.

|

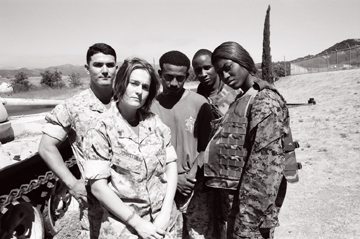

The realities of war cross boundaries of age, race, and gender. Left to right, Marine Cpl. ‘Yoshi’ Yoshida, Marine Cpl. Mischelle Johnston, Navy Lance Cpl. Quentin Givens (Q), Watts, and Marine Sgt. Kisha Pollard (Miss Flame) all contributed to the c.d.

The realities of war cross boundaries of age, race, and gender. Left to right, Marine Cpl. ‘Yoshi’ Yoshida, Marine Cpl. Mischelle Johnston, Navy Lance Cpl. Quentin Givens (Q), Watts, and Marine Sgt. Kisha Pollard (Miss Flame) all contributed to the c.d.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Frontline Rhymes

U.S. soldiers are telling their stories of Iraq through hip-hop.

By VINCE DARCANGELO

Army Sgt. Christopher Tomlinson would see some heavy action during his time in Iraq, but on the night he and his MP unit rolled up on the truck accident, he’d not yet personally witnessed the human toll of war. A Humvee in his convoy had flipped and rolled into a ravine; it was his unit’s job to get it out, and Tomlinson thought it would be a routine operation. Despite the desert surroundings, the ravine was waist-deep in water.

“They were driving at night, and that country will sneak up on you,” Tomlinson said. It wasn’t until he and his team leader had hooked up a chain to the wrecked Humvee that he realized something was terribly wrong. “I saw a boot,” he said. “It hit me: ‘Oh, my God, there’s somebody in there.’”

His gunner, a bodybuilder from Detroit, climbed into the water and grabbed the front of the Humvee to help rescue the trapped soldier. The rest of the team pulled the soldier from the wreckage and carried him out of the water. As Tomlinson and the others performed CPR on the man, the war in Iraq became very real to them.

“For the first time the mortality of the whole thing hit me. We’re not immortal. This is real. This is a real human that I’m trying to save,” he said. Tomlinson kept administering CPR until the other soldiers pulled him away. A medic arrived and told him to “let it go.”

It wasn’t that easy.

“I feel that I failed because I didn’t do what I was supposed to do. It doesn’t matter what happened, whose fault it was. I was staring a man in the face that I knew had a family,” Tomlinson recalled. At that point, Tomlinson realized that a distraught man at the scene had been part of the dead soldier’s unit. “He was telling me about how this guy, the corporal that passed away, had just talked to his wife, and it was his son’s birthday yesterday.”

When it was over, Tomlinson and his team drove the 15 minutes back to their Forward Operating Base Kalsu, south of Baghdad, in silence, knowing that their lives would never be the same.

“That silence hits you, and you don’t know what you’re supposed to do with that,” he said. “Not many 20-year-olds are faced with that.” But Tomlinson and some others found a way to deal with what they were feeling — a different mode of expression than you might have expected to find in the middle of the Iraqi desert, but perhaps not all that different from what other soldiers have done in other wars. When he got back to the base, Tomlinson said, “the only thing I knew how to do was rap.”

One convoy I was on ... a soldier passed away, and I didn’t know how to deal with it. I came back, and I met my man [Deacon]. He told me, ‘Why don’t we go cypher?’... We ended up going out there, and we did it a cappella ... . We ended up, both of us, with a face full of tears just because every emotion you could possibly have, that was the only way to extinguish that pain that you felt.

— Prophet, “Some Make It, Some Don’t”

Prophet is Tomlinson’s rap moniker, and he said the hip-hop music that he and his friends put together on that night and others helped him get through some hard times. “That’s all I had. Throw in a beat, turn the Xbox on, hit play, and let it go. It was me and Deacon,” a close friend. “We just went at it for hours, hours, just letting it go. If I didn’t have that there, that would still be on my conscience today.”

The events of that night became the source for “Some Make It, Some Don’t,” a part-freestyle, part-spoken-word piece on the hip-hop c.d. Voices From the Frontline, a 24-track collection of music performed by U.S. soldiers from Texas and all over the country who have served or are currently serving in Iraq. Released on April 25, the c.d. is a musical diary of the experiences and emotions of more than a dozen U.S. troops — black and white, men and women, soldiers, Marines, and a sailor — expressed through songs and spoken-word “skits.” Alternately joyous and tear-jerking, angry and introspective, the disc explores many aspects of a soldier’s life while avoiding the traps of rhetoric and sloganeering.

Most impressive is that the disc sidesteps politics altogether: It’s neither pro-war nor anti-war. It just is, giving listeners a chance to hear it straight from the soldiers themselves without the interference of politics. The songs aren’t about political ideology or election-year grandstanding. They are about the daily lives and struggles of the men and women serving in Iraq.

Tomlinson said he believes the c.d. gives people a chance to look at the soldiers instead of the debate. “Instead of [hearing] what’s so bad, which is all we get on CNN and everything else in between about what the Army’s done wrong or what this country’s done wrong — because everybody has their own opinion, which they’re entitled to — you get to hear the truth. Not the truth about whether we think this war is right or wrong, because none of us took that turn on the album. ... But just to say ... we’re there, and this is what my life is.”

The c.d. is proving so successful that its producer is already planning to release a second volume — and is talking about turning it into a movie or tv special. But as Tomlinson says on the disc’s opening track: “This ain’t for a paycheck. This ain’t for us to be known. This is for somebody to understand a soldier’s life.”

They always there for me when I’m gone away / They go to the Lord, kneel down and pray / And what do they say? “Please bring him home today” / I just want to see the light of the next day. — Pyro, “Family”

While Tomlinson was trying to stay alive in Iraq, Joel Spielman, president of punk rock record label Crosscheck Records in California, was stateside, trying to find active-duty soldiers to record a musical combat diary of U.S. soldiers in Iraq.

“I had this vision ... where someone is listening to the c.d., and it’s like you’re listening to a documentary,” Spielman said. “You’re listening to people report to you live from the battlefield.” The idea, he said, came to him while watching the HBO documentary Last Letters Home.

His vision bore fruit in the form of Voices From the Frontline. More than 30,000 copies of the c.d. have been shipped to retailers, and Spielman intends to release a second volume. He has received serious offers from movie and television companies, and on July 10 shooting will begin for a music video of one song from the disc, “Desert Vacation” by Marine Cpl. Mischelle Rae Johnston from Montana.

Spielman’s original search, for the first installment, led him to Camp Pendleton in California, where he met Marine Cpl. Michael Watts, a native of Brenham, Texas. Watts raps under the moniker Pyro — a reference to his job as an anti-tank assault man, dealing with explosives, for the Alpha Company Raiders, 1st Battalion 4th Marines. He finished his second tour of duty in Iraq in March 2005.

“One of my buddies came to me and told me that there was a record producer looking for soldiers from Camp Pendleton to rap on a c.d. about Iraq,” Watts recalled. “I was like, ‘Yeah, tell him I rap and give him my number.’ I didn’t take it serious. Next thing you know, Joel called me and was like, ‘Hey, I want you to be on the c.d.’”

Watts said he had hip-hop aspirations prior to joining the military, dating back to his pre-teen years in Brenham. He began freestyling — improvising lyrics over a beat, the root of all hip-hop music — when he was 12, learning the skill from his cousins. It wasn’t necessarily a voluntary choice.

“I didn’t know how to rap, and [my cousins] threw my ass in the lake,” Watts writes in the liner notes of Voices From the Frontline. “After that I started to learn how to freestyle.”

Watts had already begun rapping in clubs and doing some studio work before he enlisted in August 2002 (on the c.d. he raps about signing up while he was in high school). But Voices is his first release. His primary influences, he said, are underground Texas rappers such as Chamillionaire, Lil Flip, Mike Jones, and DSR. He also draws influence from mainstream rappers such as Jay-Z, Dr. Dre, and Snoop Dogg, but his mic style is his own.

“Because I’m from the south, from Texas, I have a, well, out here they tell me I have an accent,” he said with a laugh. “A Southern slang. A Southern drawl. That’s more along the lines of how I rap.”

He’s excited about his work being released nationwide, but his songs on Voices From the Frontline aren’t career-oriented. They are simply a way for Watts to relate his experiences in a medium through which others can “understand exactly what we’ve been through,” he said. “It’s not a game over there. It’s hard on a lot of families. People really don’t understand what it’s like over there, so we’re just trying to explain to them to the best of our abilities.”

“I could have just talked on the c.d. and got my point across, but I think music attracts a lot of people,” he said. “For me personally, music is an easier way for me to express myself. I get more into it. More feeling comes out of it.”

On Sunday, Watts and Tomlinson will appear on Fox & Friends on the Fox News Channel. The two will perform “First Time,” a song written by Watts and another rapper, Lance Cpl. Quentin Givens (Q), and discuss the making of Voices From the Frontline. The songs “First Time” and “Family” — by Tomlinson, Watts, and Givens — will also be heard on the Discovery Channel in two-minute spots over Memorial Day weekend.

“Family” carries particular significance for Watts, who wrote about the hardship of being separated from loved ones. “It pretty much explains how we feel and how our families feel,” he said, “what it’s like to be away from your family, what’s on your mind, what’s on their mind.”

The television appearances and upcoming music video should result in more record sales, but for Spielman, the greatest satisfaction comes from the personal responses he’s received “from soldiers telling us that this c.d. has given so many people in the military an outlet for their pain, literally.” The most touching letter, he said, came from a wheelchair-bound Vietnam vet in a VA hospital in Los Angeles. He said of listening to Voices From the Frontline: “Today I saw the first sunshine in a very dark world.”

I can’t word it any better but to tell you this / If it was up to me it never would have came to this / But it ain’t, so I gotta keep my feet in the paint / If I had a wish I’d wish you had to never see those tanks ... I pray every day to have peace with you / That’s why I’m writing this letter / That’s the least I could do / All words in this letter, with truth they were spoken / I’m sending this to you / This is my condolence.

— Amp, “Condolence”

In April 2005 after e-mails back and forth, Spielman traveled to Fort Riley in Kansas to meet Tomlinson in person.

“I told [Joel] about as strictly as I could that soldiers are down to work,” said Tomlinson of his early conversations with Spielman. “When we’re doing something we believe in, we do it to the fullest. But if you screw us over we’re your worst nightmare. I said I don’t want to do something about how much money we can stack up for the label or how much money is gonna be in my pocket. Having money is everybody’s dream in the world, but this is much bigger than that. This is the opportunity to speak for 140,000 of my friends, brothers, and sisters that are over there fighting right now.”

All of the recording of the album was done stateside. It proved to be a logistical challenge, since many of the soldier-singers were about to be sent back to Iraq. “The songs were all done in one take because we weren’t afforded the opportunity for [the soldiers] to come back and work on it again,” Spielman said.

As the project’s executive producer, Spielman decided not to interfere with the content of the MCs’ raps, even though that could have potentially resulted in a collection of politically charged and perhaps contradictory statements.

“I wasn’t sure what direction it was going to go,” he said. “There could have been divisions in the c.d. I said, ‘I’m just going to let it happen naturally.’ No one ever got into that. I said, ‘Just tell me your life story.’

“There was no coaching, and it ended up not becoming political,” he added, “although some of the songs you can take into your own context. There’s some tragedy.”

Soldiers appearing on the disc alongside Watts, Tomlinson, and Mischelle include MCs Deacon, Q, Amp, Miss Flame, Truck, and Machine, many of whom are currently deployed in Iraq. Roughly half of the MCs are in the Army, the others in the Marines, with at least one Navy rapper.

Together they spit rhymes about their struggles and experiences overseas, such as dealing with being apart from family, coping with the deaths of friends, coming to terms with taking others’ lives, and how it feels to come home after a year in the desert. Even gender issues are addressed — Miss Flame discusses the unique challenges of being a female soldier in the frenetically paced “Girl at War.” (“Decision-makin’ isn’t easy for a girl at war / Shit, I could get shot too, just as well as a boy / And you’re lookin’ me up and down ’cause you’re thinkin’ I’m weak / ’Til you see me in Iraq and I’m patrolling the streets.”)

Perhaps the most poignant track on the disc is “Condolence” by Marine Cpl. Anthony Hodge (Amp), a rap based on a letter he wrote to the wife of an Iraqi soldier he killed.

“We said, ‘Just do a song,’” said Spielman. “He goes, ‘I’ve got these letters I wrote when I came back from my first deployment.’ When he played it, I actually wept. He was just apologizing for the losses he’s caused. It blew me away.”

In the song’s second verse, Amp asks for direction, but more than that, he asks God to look after the widow: “Whatever you could do to give her assurance / When she is weak could you give her endurance / If you could, clear her heart of discontent and hate / If she gets lost in this world could you show her the way ... If there’s a spot for me in Heaven, could you give it to her?”

“The first time I listened to that song and he says, ‘If there’s a spot for me in Heaven, could you give it to her?’ tears welled up in my eyes,” Tomlinson said. “Damn, imagine how that feels to say that I’d give up what I have for a stranger because he felt guilty about what he did. That’s something that will be with him for the rest of his life.”

The song hit home for Tomlinson, whose wife Kim, also stationed at FOB Kalsu, was almost killed in an ambush. “A bullet went four to six inches in front of her face,” he said. “Four to six inches and my wife and my son wouldn’t be here.”

Tomlinson also explores his own mortality in the song “One Hour Before Daylight,” which he wrote about a particularly dangerous mission that he wasn’t sure he would survive. Knowing they were headed into hostile territory, Tomlinson and his soldiers prepared for the mission by writing their blood types on their rib cages and boots. He writes in the c.d.’s liner notes: “We were loading up our vests with the grenades and ammo. It was time to go. I looked to my fiancée Kim for reassurance. All I saw was a face full of tears.”

He made it back from that mission but almost didn’t survive a surprise missile attack during some down time. He and some other soldiers were tossing a football when the missile hit. Tomlinson said he would have been killed if not for an errant pass from a medic. He ran to fetch the overthrown ball when the missile hit 10 feet from where he’d been standing. The event is chronicled in the freestyle rocker “Raiders in Najaf.”

Clearly, experiences like these changed their lives. As Watts sings on “Ain’t the Same”: “I ain’t the same man I was about three years ago.”

“You look at life differently,” said Watts about what he learned from his experience in Iraq. “You learn to never take things for granted, small things like running water, stuff like that.”

After attacks and shit like that you look for ways to cope with it or ways to actually feel like you’re normal ... We’d come out of the chow hall in the back — there’s like a little chill area in the tent — and we’d just rhyme for hours upon hours about anything and everything. All your emotions could come out, and everybody’s equal. Ain’t no ranks. Ain’t no sergeants, privates. Everybody’s the exact same.

— Prophet, “Ways to Cope”

Voices From the Frontline, Spielman’s “musical combat diary,” offers listeners a glimpse of a world most will never know firsthand. For the soldiers themselves, though, hip-hop served a more immediate function. Most of the raps, such as those on “Some Make It, Some Don’t,” “Rest ’n’ Peace” and “Raiders in Najaf,” originated as catharsis, a way for the soldiers to process what they were experiencing.

“Everyone has their way of venting and relieving themselves and relaxing,” said Watts. “Some people like to walk, some people like to draw. For most of us, it’s just music. A lot of people just like to listen to music, but me personally, I like to listen to it and write it.”

Tomlinson said that many of the soldiers got together in cyphers — a circle of ad-libbing rappers, playing off one another — that brought together officers, noncoms, and privates. In the cypher, everyone was equal, he said, giving everyone a chance to escape the hierarchical structure of the military and providing a unique opportunity for the Army’s rank-and-file to express themselves.

“In the Army we all have rank structures. To have a private come up and talk to a sergeant, it ain’t gonna happen. [But] you turn a beat on and let them talk to each other through music, it’s not disrespectful. That’s how it was,” said Tomlinson. “My privates that were into rap could come out and rap with me and not have to worry about it. It actually helped them out because it allowed them to let their guard down and not have to worry about getting yelled at. It gave them a way to relax. We did it together. It brought us closer together as a team, unifying us.

“I don’t look at it as being unprofessional because it wasn’t a disrespectful conversation,” he added. “It didn’t pertain to the Army. ... [T]he next day he wasn’t calling me Chris in the truck. I’m still Sgt. Tomlinson; he knows that. But it gave him that 20 minutes to actually feel normal, and it gave me that time to feel normal, like I was back home talking to my friends. Everybody out there, regardless of if they’re a private or a master sergeant, we’re all friends or else we wouldn’t fight for each other so hard.”

It’s a release valve that, at least musically speaking, wasn’t available to earlier generations of soldiers. However, Tomlinson sees examples of hip-hop in different forms in earlier wars.

“Their way out, their way to express it was poetry,” he said. “I look up everything on the internet, from WWII to the Civil War, of poets just writing what they can write to put it out there. Well, half of hip-hop is poetry.”

Spielman likens it to a scene in the Civil War film Glory. “There’s a scene before they go into their final battle where most of them get killed, and they’re just hymning. They’re freestylin’,” he said. “They were clapping hands and just going back and forth with each other. It goes back to those times. ... They’re just clapping and the chorus is, ‘Oh my lord, lord, lord,’ and each of them has their own part where they just make things up about what they’ve been through together. If that’s not freestylin’ I don’t know what is.”

Soldiers’ letters have served as both inspiration and lyrics for songs in other musical genres as well. Last year, the punk band The Dropkick Murphys released “Last Letter Home,” a song that incorporated excerpts of correspondence between Sgt. Andrew Farrar and his family prior to Farrar’s death on the battlefield. Tomlinson refers to the grunge band Alice in Chains and their early-’90s hit, “Rooster,” the lyrics of which were taken from a letter the lead singer’s father wrote while serving in Vietnam.

As for hip-hop, Tomlinson said the influence of the genre extends beyond the younger soldiers who grew up with the relatively new musical style. High-ranking officers have acknowledged the significance of hip-hop and incorporated it into the lives of soldiers. Rap battles have become a regular part of military events, such as talent shows and holiday celebrations.

The assimilation of hip-hop culture into the military has even attracted an unlikely hip-hop fan, Tomlinson said. “My 70-year-old grandmother listens to this c.d. and loves every word of it.,” Then he laughed. “Well, she has the clean version, so she loves every word.”

It’s been 10 months, I’m going home / Call my peoples on the phone / Tell ’em that I’m coming back / Fold my clothes and grab my pack / Then I’m gone, in the sky / In my plane I’m flyin’ high / Cloud Nine, I’m flyin’ by ... Hugs and kisses, so much joy / Man, I’m back, holla at your boy.

— Amp, “When I Get Home”

In 2004, Tomlinson came home and married his fiancée, Kim. Reached by phone at his home in Delaware a few weeks ago, just prior to the release of Voices, he was changing their son’s diaper. Were it not for the baby, he said, he’d be back in Iraq.

“My reason for coming off active duty was that I lost a personal friend of mine that went back for a second tour of Iraq and had a 5-month-old daughter,” he said. “At the funeral they played a video of him reading a book to his child, and I had just had my son, which completely changed my life. I decided that was something I couldn’t do anymore.

“I love my service. I love my country. I love the Army. It’s all I know — I’ve been doing it since I was 18,” he said. “But the fact is, waking up every day and not being able to enjoy every minute with my son because I kept worrying about when I was going to leave — I just couldn’t deal with it no more.”

But he also couldn’t stay away. Tomlinson came off active duty in August 2005, and he was out of the military for exactly 22 days. Then he joined the National Guard.

“I honestly missed training soldiers, which is what I was good at,” he said. “Plus the pay and benefits in the military is a lot better than it is anywhere else.”

Now in his mid-20s, Tomlinson refers to himself as a “lifer,” and as a recruiter he is able to stay connected to the service, even if he’s not a part of the Army.

“Being able to show other kids who are 17, 18 years old — and even up to 39 now—what we have to offer and what we can do for you and [being able to]still be a part of [the military] and still be around soldiers, it’s the best job in the world to me,” he said.

Having a popular hip-hop c.d. on the music charts certainly won’t hurt. But ultimately Tomlinson wants Voices From the Frontline to be taken at face value.

“I’m hoping the album is looked at in the way that we meant for it to be looked at,” he said. “It was to speak on behalf of our brothers and sisters that are there. It was on behalf of what we’ve seen and gone through to give the American public somebody to identify with ... . The beauty of being able to open my mind and say, ‘OK, instead of speaking for myself, I have the opportunity to speak for everyone I know,’ that’s a blessing.”

Tomlinson also made the point that the singers on Voices don’t glorify the violence of war — and he has a problem with other rappers who do. “Watch this, I’m gonna have 900 rappers come at me for this one, but it comes down to the people who glorify it: Have they ever done it? That’s how I look at it. People that want to sit there and glorify it through their music because it’s mainstream and popular — have you ever taken somebody’s life before?

“You know who’s done it, because we don’t talk about it, or we talk about it in a different light because it’s not glorious. I don’t see how anybody can tell a 15-year-old kid that it’s OK or that it makes you cool, because it doesn’t. I know that first-hand. Every birthday, every holiday, I live with the fact that somebody ain’t there, and it’s because of me.”

Watts, meanwhile, is nearing the end of his active duty enlistment. When he’s done with military duty, he wants to start his music career in California and then, when that gets off the ground, move home to Texas.

Until then he wants his Texas brethren to know he’s keeping it real on the Left Coast. “I’m just out here [in California] trying to pursue my music career,” said Watts. “I’m always gonna represent my state. I’m always gonna represent Texas.”

For more information, visit www.voicesfromthefrontline.com.

Vince Darcangelo is managing editor for Boulder Weekly, where a version of this story first appeared.

COOLING THE TROOPS

Songs like those of Sgt. Chris Tomlinson on Voices from the Frontline help soldiers deal with their feelings, but it’s his mom who’s helping the troops deal with the heat.

“Back in June of ’03 I wrote an e-mail home and said it’s hot — real hot,” Tomlinson recalled. At the time his unit was doing night raids and having to sleep during the day — no simple task considering the temperature in Iraq often cracks 110.

His mom, Frankie Mayo, heeded the call and founded Operation AC. “We sent 11 air conditioners to make a sleep tent for the MPs that were doing night raids so they could have a cool place to sleep and rest,” she said, “so they could be 100 percent when they went out.”

Mayo and Operation AC eventually got Home Depot to donate hundreds of air conditioning units to ship overseas, in addition to numerous private donations. To date, the nonprofit group has sent more than 9,400 air conditioners to soldiers serving in Iraq, despite a run-in with the postal service, which initially refused to ship the units because they contained freon.

And she didn’t stop there — she moved from coolers to boots.

“The Army gives you boots, but they’re not the best in the world,” Tomlinson said. “A lot of soldiers were paying $99.95 for these boots from Ultima. My mom heard about this, and she said, ‘I can’t have this.’ So she started sending boots to my whole unit.

“It gave her something to not only help her son but to feel like she was a part of my life,” he said. “It gave us hope. It gave us somebody to identify with while we were there.”

Since its formation in 2003, Operation AC has expanded to include pretty much every item you might think of (socks, toothpaste, toilet paper, feminine hygiene products, bug spray) and many that you probably didn’t (DVDs, dominoes, cameras, Beanie Babies). All told, Mayo said the organization has sent more than $2.3 million in supplies.

Perhaps Operation AC’s most important delivery was medical supplies that arrived in Iraq just before the UN headquarters building was bombed in 2003. The supplies were used in treating victims of the blast and directly saved the lives of many of the wounded.

Mayo was gratified to have been able to help the wounded people, but she downplays her contribution. “I don’t feel that I did anything big,” she said. “I’m just trying to do something good.”

Operation AC includes an Adopt-a-Soldier program, begun by Mayo’s daughter. The nonprofit also sends get-well cards to wounded soldiers and ships clothing and other supplies to an Afghan orphanage.

Mayo makes it clear that there is nothing political about Operation AC. “I’d just like to say that supporting the troops has nothing to do with supporting the war,” she said. “It’s just about being human. You’ve got to be human first.” — Vince Darcangelo

For more information, or to donate, visit

www.operationac.com.

Email this Article...

Email this Article...