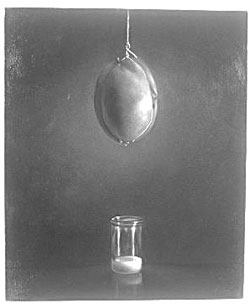

Like most of J.T. Grant’s still lifes in ‘Bęte Noir,’ ‘Mango Juice’ is Old World via contemporary vibe.

Like most of J.T. Grant’s still lifes in ‘Bęte Noir,’ ‘Mango Juice’ is Old World via contemporary vibe.

|

| Bęte Noir, by J.T. Grant\r\nWilliam Campbell Contemporary Art, \r\n2935 Byers Av, FW. \r\n817-737-9566. |

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Evil Doers

Painter J.T. Grant views the apocalypse through the eyes of assorted masters.

By ANTHONY MARIANI

The image that most visitors to William Campbell Contemporary Art will likely take from the gallery’s current paint-loving show, J.T. Grant’s Bęte Noir, is of President Bush portrayed as Jesus. Shown from the naked, boyish torso up, Dubya stands clasping a golf club in lieu of staff, sporting a wire garment hanger halo, and holding up crossed fingers. His gray hair hangs down to his shoulders, and the look on his face is that of someone being cut off in mid-sentence. Behind him — beneath an ominous, bruised daytime sky that would spook Caravaggio — a factory spits black smoke, and a vulture is perched on a dead tree.

The painting is memorable, but that’s about all. That “The Blasphemous Dream of Crawford Shrub” is probably what most viewers will discuss — and is precisely what I’ve chosen to write about — says a lot about this volatile time in which we’re living, smack dab in the middle of one of the most important U.S. presidential elections ever. During any other year or five years or decade, I’d dress down Grant, one of Texas’ most sought-after artists, for committing the unpardonable sin of preaching (in a tiny, shrill voice) through his art, but this time, I’ll let him slide — not only because getting the “Shrub” out of office trumps just about every other concern, but because the rest of Bęte Noir kicks serious, non-pedantic, non-political ass.

Grant, like many of his neo-something-or-other contemporaries, marries Old World styles and forms, specifically those that blossomed in Eastern Europe and the Netherlands during the latter-period Dark Ages, to New World pessimism. The nudes, skyscapes, and still lifes that populate the exhibit aren’t exactly inviting and reassuring. They’re troublesome. OK, they’re downright scary as hell.

“The Martyr’s Mother” depicts the upper body of a beautiful naked pregnant woman, turned slightly to one side, with her foreground hand over her belly. Behind her are a horizontal piece of rich brown wooden furniture, partially covered in red drapery, and an empty, blue sky pierced at intervals to her right with distant telephone poles and to her left with distant streetlamps. Her head is covered in a squarish piece of cloth, fastened tightly at each corner by strings that lead beyond the edges of the canvas.

Nightmarish? Yes. Beautiful? Absolutely.

The woman’s soft skin glows a preternatural, fleshy, lively pink in perfect contrast to the dour wood behind her. The shapes — squares, lines, and circles — also work together to form a new type of unexplained geometric iconography. Unlike that found in Medieval paintings, it doesn’t add up to a damn thing, religious or otherwise.

Equally surreal, yet more dismissive of bourgeois history, are Grant’s still lifes. No highfalutin’ vases and chalices here. Think instead of mangoes and heads of lettuce. Nearly every object is surrounded by shadows deeper than starless midnights but is somehow illuminated, perhaps by its own indefatigable presence as a work of Grant’s quick-witted hand.

The artist’s most disturbing non-narrative motif, however, is the sky. In places deliriously orange with promise, sometimes depressingly bright blue with inchoate infinity, often alternately scorched in frenetic streaks and static canopies of pitch black tinged with purple, Grant’s skyscapes initiate the frequently apocalyptic mood as quickly as the Requiem. In “The Renunciation,” the expansive, gently darkening sky that frames the lone character — a standing male nude seen with his back to us from the butt up, his bald head cast downward, and his hands occupied by boat oars — portends evil. The terrifying prospect summoned by this painting is echoed in a few other pieces, most notably “6:48 PM,” a long and thin horizontal canvas of nothing but menacing sky. The upper two-thirds is a vacant off-white, the bottom left-hand corner a searing orange, and the rest an angry black scattering from the center of the work into angular shrapnel on the left and curvaceous storm cloud formations on the right.

None of this would be nearly as evocative if not for Grant’s precise brushwork. While he occasionally phones in some of the shadowings and for some reason leans on a lot of visual verbiage to achieve depth, he manages to keep the flaws in his strokes relatively hidden. You must look really closely at Grant’s paintings to see the puppet strings.

While not as subtle, his “symbolism” is as significant as his Old World stylings. The loaded imagery that informs nearly every piece on view is, unlike the heavy-handed imagery in “Crawford Shrub,” purely Grantian, which is to say purely non sequitur. If there is meaning to any of the visual motifs scattered throughout Bęte Noir, then only the artist knows their connotations — and he’s not sharing.

Strings — hanging from unseen ceilings or binding bags around human heads — are everywhere. Their purpose appears to be twofold and surprisingly practical: They add visual depth while remaining relatively unobtrusive and, by daring to impose their insignificance on Art, keep things from becoming overly serious. Who knows what the hell they mean? Like Grant’s boat oars and bagged heads, they seem to exist merely to serve the artist’s muse.

A little bit of lighthearted mystery in an exhibit is a good thing. One of the greatest aspects of contemporary painting is coming in contact with an artist who may not know where he’s going but damn if you can’t help but follow him. J.T. Grant may be the only soul with the key to his visual secrets, but he makes you feel as if you’re in on his joke. He’s persuasive, in ways that a little spoiled Texan who stole the most powerful job in the world isn’t.

Email this Article...

Email this Article...