William Bryan Massey III strikes a redneck poster-boy pose.

William Bryan Massey III strikes a redneck poster-boy pose.

|

An Anti-Hero gathering typically results in as many pronouncements as empty beer cans.

An Anti-Hero gathering typically results in as many pronouncements as empty beer cans.

|

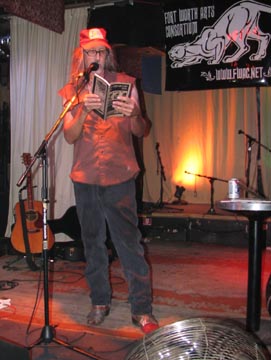

Massey spews forth at a poetry reading.

Massey spews forth at a poetry reading.

|

The mastermind behind www.anti-heroart.com, Dirty Howie just wants to get a laugh.

The mastermind behind www.anti-heroart.com, Dirty Howie just wants to get a laugh.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Art for Beer’s Sake

There’s intellect in them thar trailer parks.

By ANTHONY MARIANI

One sunny Saturday afternoon not too long ago at a countrified abode in Aledo, self-described “redneck poet” William Bryan Massey III had about a dozen people over for homemade Tex-Mex, cheap beer, and expensive tequila. The occasion? Just hanging out. The crowd included members of an online community called the Anti-Hero Art Collective, of which Massey — an almost wholly toothless, curmudgeonly stick figure topped by long, scraggly gray hair — serves as both chief contributor and poster boy.

In between penning spoken-word poems, short stories, and pseudo-journalism, or making short films and taking photos, the Anti-Heroes self-medicate heavily. Even though they prefer getting drunk or high alone or drunk and high alone, they don’t mind the occasional get-together. Their parties are always laid-back — frat boy-ish antics are severely frowned upon. Youth has long since left the Anti-Heroes and most of their friends. Everyone is either fortyish or getting close. The rules to drinking AHA-style are blood simple: Beer is consumed from either a plastic cup or the cold womb of the aluminum can, and the hard stuff is taken from either a shot glass or the plastic cup that you’ve just drained of beer. No bodies held aloft and upside down over a keg. No tubes. And, for the love of God, no martini glasses. Alcohol is drunk straight and “like a man,” the guys say. Ain’t no need to get hammered fast. Your self-loathing should be enough to keep your lips — and your liver — busy.

The belief that everything sucks, including the reflection in the mirror, informed a vast majority of the party conversation. Talk shifted from the writings of Ayn Rand, Nietzsche, and the Anti-Heroes’ hero — the original white trash Shakespeare, Charles Bukowski — to sports, education, race relations, you name it. There were almost as many pronouncements as empty beer cans; nearly every syllable of every word burned with disregard for politesse and finesse and was laced with just enough poison to bite. Though a typical Anti-Hero soiree rings with a lot of laughs, you get the feeling that contented people don’t speak and think like these guys.

Self-loathing also fuels most of the art on www.anti-heroart.com. “Life,” writes Anti-Hero webmaster and ringleader Dirty Howie, is “the brief nightmare between comas.” And love is hardly a many-splendored thing. In his essay “Alcohol and the Blues,” Anti-Hero Scary Gary writes: “Fuck love. There is no such thing. There is only money and hatred.”

The overarching AHA ethos appears to be: Enjoy what little you can while you can, even if it’s only your perceived moral superiority. In his poem “The Excape,” creative speller Massey writes: “Hemmingway had his / ornage juice and / bull fights. / Miller had his / lice and porterhouse steak Paris / Sylvia had her / cook stove oven. / Bukowski had his / whores and horse racing. & BEER / all i have is / Wal-Mart. / but that’s alright / cause / that’s all / i / fucking / need. / humanity walking / around in all / bar code sizes. / Wal-Mart is where / i go to observe ... the human slaughter.”

The collective’s web site went up in the late 1990s, around when NASCAR, Jeff Foxworthy, and Dubya made being a redneck socially acceptable and when the internet began making inroads on traditional publishing outlets. Said Dirty Howie: “I have no aspirations to make a dime off the web site. ... I just simply want to entertain folks, give them something to laugh at, and to take their minds off the serious business that is life, for the moment.” The site gets 50 to 60 visits per day, according to Howie, and the number of e-newsletter recipients has risen by 15 to about 80 over the past few months.

The Anti-Heroes are grown men who work at various, OK-paying day jobs; the collective members who have families are — dare we say — loving. Massey is adored by his two adolescent boys. Tammy Gomez, a stalwart of the independent literary scene, vouches for Massey as a good dude despite his frequently caustic diatribes. Gomez believes his shtick is just that — a persona wrapped around a rather peculiar, rather individualist Texas male. “When you get to know him, you realize that he’s a reasonable, open-minded guy,” she said. “He’s also an awesome father, and he deserves credit for that.”

The Anti-Heroes still live up to their title. The balm that soothes their pain is art — coupled with copious amounts of intoxicants. By writing what they really feel, which is inarguably a brave act, they repulse the average reader. Success then is not measured in dollars and cents but in feedback, positive or negative. AHA has been mentioned in various underground publications, and the group’s site was once featured on TechTV, the now-defunct but hugely popular network dedicated to computer geekarama. The negative responses usually take the form of pissed-off letters to the webmaster. Darryl and Maria write: “what kind of shit you selling man. I took a second before releasing this tirade, but, hell, take a close look at your fuckin’ self. Fuck you.” In response to an unidentified AHA essay, Thomas writes: “Those are the limits of your life you pathetic piece of shit. Stay on your meds, wanker.”

The Anti-Heroes’ following, expectedly, is small, devoted, and from all over — New Jersey, the U.K., Prague. A women from South Australia wrote Howie to tell him she was throwing an “Anti-Hero party”: “I have some chilli [sic], beer, blunts, porn mags, and fireworks. Have I got it covered? If there is anything missing from this lot, your help would be appreciated.” The letter ends with: “We are documenting our Fort Worth Party with a digital camera. Would you like some happy snaps sent your way?”

The main cogs in the AHA machine are Massey, Howie, and Gary, plus two relatively young turks, Motel Todd and Ben LaRosa. Massey, Howie, and Todd live in North Texas; Gary and LaRosa call California home. The Anti-Heroes are united in their singular devotion to free-spiritedness, mainly the kind that gives the finger to political correctness. Each artist is in some way a Grade-A redneck. As Massey writes in the poem “WHITE TRASH & not just a little bit”: “you don’t have to live / in a Trailer House to / be White trash / you don’t have to drive / a ’74 Trans Am w/wings / & mullets riding around / listening to / AC/DC / DOKKEN /KROCUS / IRONE MAIDEN / AND KISS / AND YOU DON’T / NECESSARILY EVEN HAVE / TO BE WHITE / YOU JUST NEED TO BE / CAPABLE OF DOING STUFF / LIKE / emptying your cat-litter / box right out in the / middle of the street bout / once a month.”

In other ways, each artist is also not a redneck. What separates the Anti-Heroes from your run-of-the-mill pack of hicks is self-consciousness, the ability to recognize and accept that no matter your color, creed, or origin, you’re as fucked-up as the next guy. That, and Massey, Howie, Gary, Todd, and LaRosa each have a penchant for articulating disgust at the world through art, not the reddest of redneck preserves.

Gomez appreciates the Anti-Heroes for the purpose they serve. “It’s valuable to acknowledge them,” she said. “They’re showing a regional inflection, of what literature should sound like from this part of the country, that is not represented well here. ... They’re doing something very colorful, nuanced with Texas-Southern politics.” It’s all right, Gomez said, “to acknowledge the literary contributions of poor white guys. They deserve a say-so, too.”

Normal folks and non-artistic rednecks may not understand. Most people figure that life in Trailer Park, U.S.A., is an endless, circular dead-end in which the A.C. never works, the barefoot children are always hungry and dirty, and the fear of outsiders — of anything that suggests change — permeates every thought, word, and deed. Yet the fact that the low life, as the Anti-Heroes call it, is unappealing and borderline scary explains why it should be mined for art. The guys see themselves as correspondents, reporting from the heart of the country’s seedy, smelly, chicken-fried underbelly. “It’s reality,” Massey said. “I’ll write about something that’s really there and that I can get a hold of. I come from the gritty side, rather than the pretty side. People write about pretty stuff, but I can’t write about it, ’cause I’ve never been there. People read my stuff and tell me I’ve been to places they’d never dream of going to.

“I grew up on mac and cheese, baloney sandwiches, and Kool-Aid,” he continued. “Y’know, we couldn’t sleep on our backs with our mouths open ’cause the roaches would fall in. I’m sure people have been through worse, but I don’t see none of them sittin’ at a typewriter.”

Redneck pride is a toxic byproduct of the multi-cultural-friendly 1990s, when authority figures from the art world to MTV encouraged Americans to be themselves and take pride in their unique characteristics. Though addressed specifically to minorities, the message filtered down to the rednecks, who duly ran with it. Some would say, ran with it all the way to the White House.

Of the redneck’s multiple qualities, the Anti-Heroes celebrate his most definitive — the freedom to say, do, and think as he pleases. The enemy, as Massey makes clear in his poem “WHITEPOX,” is dishonesty and its enablers:

I’m a racist, a human racist / I hate everybody, everybody

in the human race human / waste inhuman for

my taste sandniggers /wetbacks chinks wops

niggas gooks and them / sorry ass

white people

Please don’t be offended / if I left you out

And I’m prejudiced also / cause the ones I dislike

the most are the / white ones. I’m ashamed

to call myself white / I wish that I had as much

$ as Michael Jackson / cause if I did I’d be just

like him and change / my race and keep on doing

it till I created a whole new / race for somebody to

hate A brand new / fucked up society

the WHATEVERS

the WHOKNOWS

the WHATINTHE

HELL’STHAT’S

and the one big

GROUP

THE WHO IN THE

HELL CARES PEOPLE

Why in tha hell am I / trying to fool none of

this will ever happen / so we might as well

just kick back / relax and all get

along together / Let’s all drink a bunch

[of] beer smoke a bunch / of pot and all go

shopping at / WAL-MART

FUCK

it ...

Where’s that remote?

“All this angst builds up,” Howie said. “Some people run marathons. Some people play golf. But for me, I need to get it out.” He paused. “Instead of going to the psychologist. I’ve always liked to read. I’ve always liked to write. [Art] comes naturally, for all of us.”

The roots of the Anti-Hero Art Collective go back to Dirty Howie’s self-published ’zines, including Experiment in Words, Losers Are Cool, Bukowski and Serial Killers (Howie’s photocopied paean to one of his biggest literary influences), and the mag that Howie thinks most locals remember, A Bug In My Fries. He had become interested in ’zines after getting published in a few. “I looked at them, and I said, ‘I could do [my own ’zine],’ ” he said. “I started corresponding with other ’zinesters, and my [enterprise] expanded.”

At the time, Howie was a journalism major at Texas Christian University and a regular contributor to the school newspaper, The Daily Skiff, where he would eventually become sports editor. He was also covering high school football for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram as a stringer. He dropped out of college for personal reasons and afterward, while working odd jobs, began writing in earnest for various non-mainstream publications.

When the internet became cheap and efficient in the late 1990s, moving his operation from pulp to pixels was a no-brainer. “When you have a circulation of 50 and you’re paying for postage, it’s just so much easier — and cheaper — to do it on the internet.” Howie said. A lot of other ’zinesters, he continued, “realized that there was a huge audience out there, and they wanted to make their creations available to those millions upon millions of internet junkies.”

Howie learned web programming through an online class at cnet.com. The design aspect, he said, came easily. Howie is now fully responsible for the look of all AHA-related product — from the deliberately cheesy home page to the Anti-Hero Art t-shirts and coffee mugs. Yes, there is AHA merchandise, and since May it has been available for sale via online clothing retailer Café Press (www.cafepress.com). Other than the several items he’s sold to some other Anti-Heroes, Howie said, there’s been only one sale, that of a trucker cap emblazoned with “Bukowski: Don’t Try.” (Apparently, AHA fans are as destitute as their “heroes.”)

Howie spends about three hours per week on AHA — designing merch or uploading assorted literary gems from the other Anti-Heroes. Creating his own art requires a little more time. He recently shelved writing in favor of filmmaking, and his uniformly Dadaist digital flicks each take about six hours to construct.

Howie is pleased with both his own and his fellow Anti-Heroes’ handiwork. Of the dozens of writers and artists he encountered in the underground press scene, Howie intentionally, gradually pared the number of Anti-Heroes down to its current handful, a group that comprises the guys he “really liked and got along with.”

Coincidentally, Howie and Massey didn’t meet until the web site was already humming. A mutual friend passed Massey’s mailing address along to Howie, and a correspondence began. “We knew of each other,” Massey said. “We’d see each other’s names in magazines,” including, most notably, Driver’s Side Airbag, the now online-exclusive ’zine that made a name for itself by publishing the scribblings of dozens of rock dignitaries, such as Henry Rollins and some members of Sonic Youth.

Massey, who began dabbling in spoken-word poetry while in jail for a minor infraction in 1989, was publishing his own handmade chapbooks. Made from six-pack cardboard, duct tape, and plain old white paper and sold on the street and in clubs, Massey’s books had the appearance of genuine trailer park artifacts — and they still do. Whether he builds 25 or 50, he almost always sells out.

With Motel Todd, Howie and Massey cruised the clubs that offered poetry readings. The Hop and the Dogstar (formerly Kerouac’s), both on West Berry Street, and downtown’s Noble Bean were regular stops. “We got tired of it, though,” Massey said. “Then Howie started doing stuff on the computer.”

Massey, who gleefully thumbs his nose at technology by continuing to produce his signature handmade chapbooks, believes he’s the only Anti-Hero who’s making any money off his artful labor. He credits his upbringing with giving him the tools to sell, sell, sell. “Must be the Jehovah’s Witness in me.”

Being an über-redneck, Massey has had his ups and downs. At the moment, he’s content: Living with close friend Hippie Steve, Massey is nearly over his recent, messy divorce; he still gets to see his two artistically inclined boys on a regular basis. He’s also cooking part-time at Fred’s Café in the Cultural District, performing steadily, and, now armed with a new vintage typewriter (his second), he believes he’s enjoying writing now as much as when he first started 15 years ago.

Massey played drums in a few local punk-ish bands around town during the 1970s and ’80s. One of his bandmates was Kevin White, the former head of the indie label and press PsychoTex. “He’s the guy who got me into writing,” Massey said. “He said when I got outta jail, he’d help me put out a chapbook.” Massey swiftly sold the first 50 copies of the 32-page Jail. Some buyers paid in cash; others, in beer or food. Massey, who was living in the bushes behind the Kimbell Museum of Art, took what he could get.

William Bryan Massey III was born and raised poor in Cleburne with his older sister, who passed away several years ago. His father, a former Army soldier, worked most of his adult life as a welder for the Santa Fe Southern Railway while also running his own peanut farm. Massey’s mother worked a series of jobs before settling into a position as a nurse’s aide at a convalescent home. Mom and Dad divorced when Bryan was six years old. When he was eight, his grandmother decided he should join her as a Jehovah’s Witness. To raise money for the church, Bryan went door to door selling magazine subscriptions. Like every other young member of the church, Bryan was also given subjects from the Bible to research and then discuss in front of the congregation. “I guess that’s when I got my first taste of getting up in front of an audience,” he said.

Massey stayed with the church until junior high school, at which point girls and rock ’n’ roll were taking over. During one of his sales calls, he knocked on a door that was opened by a girl he had a crush on. “I was in my suit,” he said. “I felt so stupid.” At around the same time, Massey also discovered that “Led Zeppelin was the greatest rock band on earth.”

School was tough. His sister had married an African-American, which was cool with the highly integrated church and with Massey; the new brother-in-law was a bad-ass drummer and more than willing to give the scrawny young white dude some lessons. But the marriage was not at all cool with the predominantly white, reactionary townspeople — and definitely not with Massey’s predominantly white, youthfully ignorant classmates.

Massey said he didn’t know the difference between black and white until the kids at school began taunting him. “I had to defend myself a couple times a week,” Massey said. “They’d say, ‘You’re the kid whose sister married the fuckin’ nigger.’ I didn’t want to be that kid, but I was.”

When Massey’s sister and brother-in-law decamped for Fort Worth, lil’ bro was not far behind, even though he had just begun his junior year at Cleburne High School. (He never went back but received his high school equivalency certificate 20 years later while in jail.) For several years, Massey traveled back and forth between the two towns, until Mom joined the family in Fort Worth.

The Fort Worth neighborhood where Massey and his extended family lived was largely African-American. The kid who was once the brother to a woman who dared to marry a black man was now referred to by neighbors as “the white motherfucker whose sister married a brother.”

Massey was tracked down by a friend from Cleburne and talked into joining the friend’s rock group. Raven, an extended jam-oriented cover outfit, was the house band at the Nashville Stop-Over, on the South Side, for more than two years. Room and board were provided. All of the Stop-Over’s employees lived in a nearby house owned by the club owner. “We played for two years, seven nights a week,” Massey said. “The party didn’t end for two years. We did too many drugs and took too many pills.”

A run-in with the law was bound to happen. Massey got a DUI in the late 1980s, and his reluctance to honor the strictures of his subsequent parole is what landed him in Tarrant County jail — and, coincidentally, got him writing.

“I like writing ’cause it’s solo and at my leisure,” Massey said. “There are no egos, and I don’t have to answer to anybody.” A long-time lover of books and stories, going back to his Jehovah’s Witness days, Massey saw writing, spoken-word poetry specifically, as a genuine reflection of himself — raw and immediate. “The most honest and best thought you have is usually your first,” he said. “And that’s what I’ve always went with.”

Self-publishing, both in print and on the web, no longer appears to be the sole province of fringe dwellers and other bad spellers. The oddly successful and extremely Pentecostal Left Behind series began as a vanity project, and the internet teems with professional writers’ blogs, including Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist Michael Chabon’s web site, esteemed New Music critic Kyle Gann’s Post-Classic, and legendary culture vulture Terry Teachout’s About Last Night.

A lot of self-published literature, especially non-fiction, is filling the gaping void in quality left by the New York publishing houses’ descent into schlock. Contrary to what Regan Books editor Judith Regan thinks, not everyone wants to read another D-list celebrity tell-all.

Many readers crave the type of punditry that permeates nearly every AHA essay, story, or film — The New York Times best-seller list almost always contains a treatise of some sort, and The Drudge Report remains one of the most-visited sites online, with more than 5 million hits per day.

The Anti-Heroes are deft at nicely feigning God-like omniscience in their screeds. The good ol’ boys are so steadfast in their skewed perspectives that mystery — the writer’s admission that he doesn’t know it all and the dangling carrot that strings readers along — often dissipates by the third or fourth paragraph. The intellectual essences of some 1,000-plus-word essays can be reduced to about two or three catch phrases. To fully comprehend some of the collective’s other non-fiction works, readers can just skim the topic sentences. The sweaty insistence with which the Anti-Heroes fight off ambivalence, ambiguity, and contemplation is, like a car wreck, banal but hard to turn away from.

The writers’ unbending fidelity to free (and inventive) speech is also what defines them. The return visitor expects the vindictive to rush toward him like rusty shrapnel from a hand grenade every time he opens an AHA story on his web browser — that’s why he keeps going back. And the Anti-Heroes try not to disappoint.

Taken as a group project, www.anti-heroart.com is one long suicide note tinged with damned, dirty hope. Gone are the niceties and formalities of “It’s been a great ride, but ...”: In their place are fuck you’s, fuck me’s, and fuck everything’s, written with such extraordinary vitriol and, occasionally, such hearty respect for the craft of writing that the writers’ pleasure can’t help but bleed through. Obvious metaphors, long-winded tangents that lead to dead ends, and painfully descriptive documentation of bodily functions form a profile of an attention-starved child who gets a kick out of laughing at his own belches.

The intro to Dirty Howie’s fiction piece “Laughing Like Killers” could be the opener to just about any of the Anti-Heroes’ pieces of short fiction — or a peek into any of the writers’ lives:

Rogers Blanko, who sat slouched deep down into the knife-slashed, blood-stained gold colored couch he found last week while Dumpster diving behind the Carnival grocery store on 8th Avenue, started his day like he did every other day: sleeping in late nursing a nasty hangover. After finally getting up about noon he popped a couple of Downyflake frozen waffles into the toaster and spread Peter Pan peanut butter over them. He washed down his yummy breakfast with an ice-cold beer. Instead of looking through the job advertisements like his Texas Employment Commission caseworker told him to do he flipped through The Fort Worth Star-Telegram looking for the Life section and the TV listings therein. He especially wanted to know what time the Dukes Of Hazzard rerun came on SpikeTV. He liked staring at Daisy Duke’s cleavage and beautiful ass. Her sensational body parts never failed to inspire him to jack off.

The desire to communicate, to hear and be heard, helps keep the Anti-Heroes not only writing but breathing. The site reeks of hormonal confusion and pulses with the psychological instability that reconciles bullying with the longing for human interaction, the marriage of the op-ed page of The New York Times with the wack-job on the street corner in a sandwich board that reads, “The End is Near!” Just about every piece of AHA writing pokes its finger in your chest and hectors you while maybe not so secretly hoping that the thrust of the poke is just right and that the timbre of the hectoring voice isn’t too shrill.

Of the media coverage surrounding the Runaway Bride, LaRosa is humorously pitiless in “Andy Warhol Wins Again” (in reference to his famous “15-minutes of fame” line): “What really annoys the shit of me, more than the horrible Southern caricatures that are his, hers and HEE-HAW’s families, more than the doom-groom who is somehow able to walk after a complete brainectomy (his backup brain, never having worn a vagina as a skullcap, still steers him) and even more than the waste of cop-shoots-donut time are her lips.”

In “Funeral in a Fart Smelling Town,” Todd limns the extent of his environmentalism, in a daffy and stilted yet you-can’t-help-but-laugh timbre. He writes that he’s not a conservationist “for the usual reasons. I have a different motivation completely. No, I’m not a black clothes wearing coffee house poetry junkie who’s into every political cause around just so he can score a piece of ass off some politically conscious — and HOT — chick wearing black lipstick and eyeliner. My reason for conservation is paper mills, those places where they take the trees that are raped from the forest and turn them into paper products. These places make your town smell like a Howard Stern produced fart!”

It’s evident that the line between autobiographical writing and everything else can be easily washed away by some alcohol. In his regular column, Scary Gary’s Place, the wordsmith delivers the literary equivalent of a bloggish diary. The most talented Anti-Hero, who can hang with any pro, Scary Gary lets his tattered, torn freak flag fly — nothing is off limits, as in the essay “Irony Skillet”:

Imagine time somehow reversing itself. The dead climbing out of graves, slowly recovering health, growing younger and younger, eventually crawling back into the womb. Lumber companies propping up forests. Oil companies pumping black sludge into the earth. Hitler coming out of his bunker, going back to painting. Humanity returning to the sea, carrying with it its centuries of death and torture like luggage.

I dream of snakes with human heads, spiders spinning stainless steel webs, your soul covered with blood, my world a toilet, you in it. All the people dead, all the insects feeding. Our eyes gleaming, our love lost, our bones all dry, our mouths screaming all the agony of all the wars of all the betrayal of the heart until there is nothing. Like a mirror I reflect what humanity has become. Look at me, young man, with your beautiful wife, your pretty children, your shiny car. Look into my eyes, see the sickness, see yourself. I have befriended the worm and the jackal and the old dying seagull. All that you despise, all that you fear, all that is you. Now these eyes see you, Mister Death, and I can’t stop laughing.

Unlike Gary’s writing, Massey’s — though based on his day-to-day existence — is semi-fictionalized and hyper-exaggerated. After Jail, Massey self-published Sister: A Small Tale of Great Distress, in memory of his deceased sibling, and then a string of titles that mostly reflect certain periods of time in his life: Stayin’ With Girls was written during Massey’s days of living with two girls in Fort Worth, and his latest, Found On Road Dead, comes straight from a recent demolition odd job that turned up a fantastic but unusable vintage typewriter. Massey has produced about 10 chapbooks in all, each about 20 to 30 pages long. “I’d say it’s about 40 percent me, 60 percent other stimuli,” he said of his work.

Massey doesn’t worry about incriminating himself or others through his verse. “You can’t be worried about that shit if you’re making art,” he said. “If you have limitations and rules, you’re not making art.

“I like to think I can make the typewriter say anything I want,” he continued. “If I start worryin’ about what somebody thinks, I need to be at Jiffy Lube or,” he stopped and then said with a laugh, “flippin’ burgers at Fred’s.”

Massey chafes at the suggestion that he’s a caricature. “I will read some serious stuff,” he said. “It throws people for a loop.”

The web site itself is also booby-trapped to shield against predictability. One of Howie’s recent movies is a straightforward, lonnng video recording of a trip to Fossil Rim Wildlife Preserve. The sounds of Howie and his guests marveling at the beauty and grace of some of the creatures are clearly audible. Not a single ironic, distasteful, or bitter word is uttered.

Howie said that if he hit the Lotto tomorrow, he’d probably still keep the site going. “It’s a hobby, something fun to do,” he said. “If I just get one laugh outta folks, that’s all I really want.”

You can reach Anthony Mariani at anthony.mariani@fwweekly.com.

Email this Article...

Email this Article...