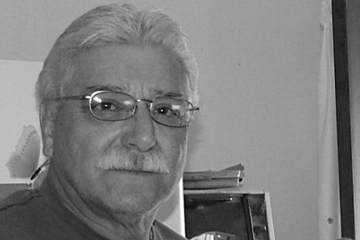

A Minuteman from Texas — who gave his name only as Haskell — scans the border near Douglas, Ariz., in April 2003.

A Minuteman from Texas — who gave his name only as Haskell — scans the border near Douglas, Ariz., in April 2003.

|

|

‘The first time they \r\ncross that line,\r\n I’ll hammer them.’

|

Garza: ‘If their elected leaders were doing their jobs, we wouldn’t have the Minutemen.’

Garza: ‘If their elected leaders were doing their jobs, we wouldn’t have the Minutemen.’

|

Simcox: ‘We’re not vigilantes.’

Simcox: ‘We’re not vigilantes.’

|

The sign reflects the belief of some extremists that there is a Hispanic conspiracy to reconquer the southwestern U.S. and rename it Aztlan.

The sign reflects the belief of some extremists that there is a Hispanic conspiracy to reconquer the southwestern U.S. and rename it Aztlan.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Uncivil Defense

The Minutemen stumble into instant opposition in Texas.

By DAN MALONE

We are not vigilantes, and we are not anti-immigration.”

Chris Simcox was talking to a fresh group of recruits for the Minutemen Civil Defense Corps. The organization, which has made headlines nationwide in recent months for its armed “citizen patrols” along the Arizona border, is branching out into Texas. The meeting at a ranch near Hillsboro on Saturday was the first of several training sessions scheduled across the state this week, and a reporter for the Fort Worth Star-Telegram dutifully recorded Simcox’s statement.

But charges of vigilantism, anti-immigration rhetoric, and racism, nonetheless, are exactly what the group has faced since it began its patrols and started organizing in Texas. In fact, you might call the meeting outside of Hillsboro a case of the group not starting up, but starting over in Texas.

The group’s first Texas president resigned because he believed some members were just as interested in booting Hispanics out of political office as in keeping illegal immigrants out of the country. Another member angered a Texas sheriff with loose talk about shooting illegal aliens. The King Ranch, one of the largest in the United States, won’t let the Minutemen patrol any of its land along the border. And the Southern Poverty Law Center recently wrote, in its Intelligence Report magazine, about finding members of a violent neo-Nazi organization among the ranks of the group’s Arizona recruits.

The Minutemen, it seems, may be facing a rough ride here in the Lone Star State.

Al Garza, the new president of the Texas Minuteman chapter, said his volunteers are only filling a void created by the federal government’s inability to stop illegal immigration. “The ones they should be concerned about is their own ... government,’’ Garza said in a recent telephone interview. “If their elected leaders were doing their jobs, we wouldn’t have the Minutemen.’’

U.S. Customs and Border Protection has about 11,000 agents patrolling the Mexican border. Even so, thousands of people elude the authorities every day. By some estimates, as many as 4 million people enter the country illegally in some years, and the problems they bring with them sometimes wreak havoc on lives and property. Just last week, New Mexico Democratic Gov. Bill Richardson, the nation’s only Hispanic governor, declared a state of emergency in four border counties that, as he told CNN, have been “devastated by the ravages and terror of human smuggling, drug smuggling, kidnapping, murder, destruction of property, and the death of livestock.’’

When the Border Patrol cracks down on coyotes in one place, the people-smugglers move to another. The pipelines through which human cargo passes constantly shift. Earlier this year, one of these human pipelines began emptying its contents in Texas’ Goliad County, more than a hundred miles from the border.

Before the Minutemen arrived, Goliad possessed the solemn distinction of being best known for a wartime atrocity committed long ago. On March 27, 1836, Mexican troops, acting on orders of General Santa Anna, marched more than 300 unsuspecting Texas prisoners of war to the outskirts of the town, took aim, and shot them to the ground. Their remains, which were later gathered and buried in a nearby mass grave, are marked with a monument to the “Goliad Massacre,” one of the bloodiest days of the Texas war of independence.

Today, the outskirts of Goliad are a battlefield of a very different struggle. Shots haven’t been fired in this war yet — but some fear it’s only a matter of time.

Bill Parmley is a petroleum geologist who lives in a rural community on the outskirts of Goliad. Earlier this year, he grew frustrated as the area around his land in South Texas was being overrun with illegal immigrants. The evidence was frequently sitting along the farm-to-market road that runs in front of his home.

“They were coming through here in a caravan, three or four [vehicles] at a time,’’ he said. “They’d dump the people, and someone from Houston would come pick them up. They’d leave them here for a week at a time. There would be 20 or 30 [people] in your driveway. You’d try to get the license plate of the first vehicle, and before you could, there would be a second vehicle.’’

Stranded for days in a strange place, the illegals did what they had to survive. Parmley said it was not uncommon for ranchers to find that their cattle, sheep, or goats had been slaughtered by starving immigrants.

Parmley and others first tried to get help from state and federal officials. They wrote and called politicians and bureaucrats. When that failed, Parmley started thinking about the Minutemen, whose patrols along the Arizona border had been making the news. He decided to contact Simcox. In June, Parmley said, he flew Simcox to Texas, and the two men agreed to form two Minutemen chapters, one for the Goliad area and another for the entire state, with Parmley as president of both.

Members trickled in as word of the newly formed organization began to spread. The group began reporting suspicious vehicles and strangers to Goliad County Sheriff Robert De La Garza. And for a while, the problem seemed to abate.

“The sheriff had come in here and seized 160 vehicles in the last six months,’’ Parmley said. “You can’t fault him and say he’s not doing something with it. He’s probably one of only three sheriffs in the state that was pursuing illegal aliens.’’ Other members of the organization, however, remained critical of the sheriff — and Parmley began to suspect they were motivated by something other than working on Goliad’s immigration problem.

Parmley said some of his members had previously approached him about “ trying to get the Hispanic people who are in office in Goliad [out] and replace them with white people.’’

But Parmley wasn’t interested. He thought the sheriff was doing a good job. And Parmley had been working on immigration problems with local officials of the League of United Latin American Citizens — an overture that further alienated him from Minuteman membership. The split didn’t seem likely to heal, and Parmley resigned less than two months after Simcox named him president.

“I don’t know of any other word to describe it other than racism,’’ he said. “They had a secret agenda before the organization ever got started. They rolled it into the Minutemen.’’

Parmley’s resignation made headlines across South Texas and seemed to confirm suspicions held by some that the Minutemen might not be so alarmed about illegal immigrants had it been whites pouring across the border.

After De La Garza learned of Parmley’s resignation, the sheriff said, he confirmed with his own sources that some of the Minutemen were working behind the scenes to get him out of office. Furthermore, he was flabbergasted when the wife of another Minuteman, in a conversation with him and other South Texas law enforcement officials, broached the possibility of shooting any illegals found trespassing. “They were talking about the illegals and what they could and couldn’t do’’ when the woman asked, “If these illegals come onto your property, can we shoot them?’’

The good relations that initially existed between the Minutemen and the sheriff’s office are now long gone.

“If they call me, we’re going to respond, but as far as an organization, I don’t want nothing to do with them,’’ the sheriff said. “They can stay out there as long as they don’t do anything illegal. The first time they cross that line, I’ll hammer them.’’

Minutemen co-founder Simcox responded to the fallout of Parmley’s resignation by appointing Al Garza as president of the Texas organization and Kenneth Buelter to head the Goliad group. Garza, a retired private investigator, lives in Douglas, Ariz., but was born in Raymondville and grew up in Pharr. He said that, for an organization fighting allegations of racism, the fact that he is Hispanic is a benefit. “I can speak Spanish,’’ he said. “Being brown-skinned is a big plus.’’

Buelter added that people should judge the Minutemen by their actions, not the words of others. “We are not a racist organization in any way, shape, or form,’’ he said. “If you watch what we do and listen to what we say, we will prove that.’’

When Garza moved to Douglas a few years ago, he said he was at first oblivious to the illegal immigration problems he would face. “I thought it was going to be tranquil, serene, and peachy,’’ he said. “It turns out I made a big mistake.’’ Dogs in his neighborhood barked constantly through the night as strangers passed through.

He contacted Simcox after seeing him on a local television news program. “Being Hispanic, I showed some concern because I thought this could possibly be a vigilante situation or white supremacists,’’ he said. Simcox, he said, took him “out in the field and showed me the different pipelines, the different trails, and whatnot, the debris that’s left behind — clothing, cans, paperwork, drivers’ licenses from Mexico. I could not believe my eyeballs.’’

The two men encountered one group of about 30 illegals. Among them was an elderly man and woman who were “showing signs of distress.’’ Simcox impressed Garza by getting the couple something to drink and calling emergency medical technicians to the scene. “That really turned me on,’’ Garza said.

“Break out the application,” he told Simcox. “Whatever it takes, I’m interested.’’

Garza acknowledges the situation in Texas “looks bad,’’ but said it was the result of misinformation. He spent time with the Goliad members and found that in “no way, shape, or form were these people prejudiced or had any sort of agenda.’’ Nationally, the Minutemen’s web site disavows any association with “separatists, racists, or supremacy groups” or associated individuals.

“A lot of the information coming through the media has been twisted,’’ he said. “The real story is simple. These people are frustrated.’’

The Minutemen have been portrayed as trigger-happy vigilantes, when, Garza said, they’re really “quite the opposite. What possible reason as a Hispanic could I have to go join a group that [has the reputation of] shooting Mexicans on a wild safari? That’s the image that’s been portrayed.”

On the other hand, Garza and other Minuteman leaders do acknowledge that many of their members carry guns on patrol — which may not make them much different from other people out in the rural parts of South Texas’ harsh landscape, where both drug runners and rattlesnakes are common.

“I won’t say there won’t be anyone who’s armed,’’ said Buelter, the new Goliad Minutemen president. “No one will be carrying long arms. If someone has a concealed handgun license and has permission from the landowner, they will be able to carry their concealed handgun.’’

Buelter said he has applied for a handgun permit but doesn’t know whether he’ll be taking a gun with him during a planned patrol all along the U.S.-Mexico border in October.

“It’ll depend on where I’m stationed. That’s one of the things that as a group we are making a stipulation. If the landowner requests that you not carry, you won’t carry. He’s liable for anything that we do.’’

As for the group’s national leadership, Simcox has already faced legal problems for carrying a pistol. In 2003, Simcox was arrested on federal firearm charges after crossing into a national forest with a concealed handgun. According to press reports, Simcox contended he was just taking a hike and did not realize he had entered federal property where firearms were banned. Park officials, however, according to press reports, said that they believed Simcox was on a patrol.

Simcox was cited for two misdemeanors — carrying firearms on park land and giving false information to a park ranger about whether he was carrying a gun, a court official said. He was sentenced to two years probation and fined $1,000, according to published accounts. Simcox is in the process of appealing the case. He was not available for comment for this article.

Garza said that carrying guns is part of the Southwestern culture. “In terms of us being vigilantes with guns, Arizona is a right-to-carry state,” he said. “I carry a gun, never used it. It’s simply a way of life out here.”

Garza said he is in the process of reorganizing the Texas chapter and recruiting members for other local groups in the state. He estimated that there are about 600 Minuteman volunteers in Texas. There is, however, no way to verify those numbers — and Parmley says the group exaggerates its membership.

“Every minute is a growth minute,’’ Garza said. But when asked for the names of other Texas Minutemen who could talk about the group’s plan, he said Buelter alone could “speak on my behalf.’’

The group is now trying to recruit members across the state for a planned month-long patrol of the 2000-mile U.S. -Mexican border in October. They plan to set up observation posts on private property where illegal immigrants are believed to travel.

Buelter said the Minutemen are in the process of persuading landowners along the border to let them come onto their property. “There’s 1,394 miles of border’’ in Texas, and all of it is privately owned, he said. His Minutemen will look to the ranchers for help in selecting observation posts. “The landowners know where the illegals come across their property,” he said.

“As we see trespassers come across the landowner’s land, we will be reporting those trespassers to the border patrol,’’ Buelter said. “That’s all we do. The only way we interact with any of the trespassers is we provide humanitarian aid.’’

One of the biggest landowners along the border is the King Ranch, and the Minutemen have not been able to obtain permission to search for illegals there. “They feel like the liability issue is too great,’’ Buelter explained.

Roger Rocha, director of the Texas chapter of the League of United Latin American Citizens, said ranchers should worry about Minuteman patrols. He said member of a similar organization several years ago pistol-whipped an illegal immigrant during a patrol on private property, and the rancher wound up being sued over the incident.

Rocha also questions how the Minutemen will be able to make meaningful distinctions among the people they encounter. “How are the Minutemen going to distinguish who is a U.S. citizen and who is not? Certainly they don’t have the authority to ask anyone for identification. They’re not Homeland Security or the Border Patrol to be doing that.

“Texas is not Arizona,’’ he said. Unlike Arizona, where the border runs through public lands, all of the Texas border with Mexico is on private land. “We are really concerned with an incident happening on the border, a loss of life, that would have a bigger impact on immigrants and Hispanics. There would be a backlash regardless of who was responsible,’’ Rocha said

Carlton Jones, a spokesman for the Del Rio Border Patrol office, doesn’t know what to expect from the Minutemen. “It’s hard to answer that question,’’ he said. “We haven’t dealt with them there.’’

Border ranchers frequently call in sightings of illegal crossings. “We’re always glad to have citizens help us,’’ he said. “Given [the length of] the border and the number of people we have to patrol, any rancher who calls us and lets us know what’s going on helps.’’

And he’s resigned to the fact that his officers soon may not be the only armed patrols cruising the border. “From the standpoint of the Border Patrol, people are allowed to do things that don’t violate the law,” he said. “If they’ve got permits for [guns], there’s nothing we can do about it.’’

When he was president of the Texas Minutemen, Parmley said, he was never keen on the idea of armed patrols. But the Arizona members, who Parmley said had been fired upon by Mexicans across the border, were intent on carrying weapons. Their attitude, he said, was, “They [illegal immigrants] could be armed, so we’d better be armed — that type of mentality. It’s a recipe for disaster.’’

“These guys are kind of playing cowboy,’’ he said. “Somebody’s going to get hurt, and some attorney is going to sue the crap out of you.’’

You can reach Dan Malone at dan.malone@fwweekly.com.

Playing Army

In Arizona, Minutemen leaders and their volunteers spouted racist rhetoric.

By David Holthouse

Vigilante militias have been capturing, pistol-whipping, and possibly shooting Latin American immigrants in Cochise County since the late ’90s, when shifts in U.S. border-control policies transformed the high desert region into the primary point of entry for Mexico’s two most valuable black market exports: drugs and people.

But the Minuteman Project raised the stakes with a highly publicized national recruiting drive and a media blitz. These maneuvers generated massive and mostly positive nationwide coverage of a small gathering of weekend warriors who engaged in plenty of bigoted talk and became, at least for a while, the vanguard of America’s anti-immigration movement.

The Minuteman Project was the brainchild of Jim Gilchrist, a retired accountant and Vietnam veteran from Orange County, Calif., and Chris Simcox, a former California kindergarten teacher who left his job and his family, moved to Tombstone, Ariz., and refashioned himself into a brash anti-immigration militant following the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Before the Minuteman Project began, Gilchrist and Simcox repeatedly claimed they had recruited more than 1,300 volunteers. But when their plan lurched into action this year on April Fool’s Day in Tombstone, fewer than 150 volunteers actually showed up, and they were clearly outnumbered on the Wild West movie-set streets by a swarm of reporters, photographers, camera crews, anti-Minuteman protesters, American Civil Liberties Union legal observers, and costumed gunfight show actors.

Their enlistees were nearly all white — although Gilchrist and Simcox had claimed prior to April 1 that 40 percent of their volunteers would be minorities, including, according to their web site, “American-Africans,” “American-Mexicans,” “American-Armenians,” four paraplegics and six amputees.

California and Arizona were the most heavily represented states among the Minuteman enlistees, but the volunteers reported from all regions of the country. Many, if not most, were over 50 years old, and their ranks included a relatively high percentage of retired military men, police officers, and prison guards. Women made up nearly a third of the volunteers, including a bevy of white-haired ladies selling homemade Minuteman Project merchandise such as “What Part of ‘Illegal’ Don’t They Understand?” t-shirts and the quickly ubiquitous “Undocumented Border Patrol Agent” badges (which bore color-copy counterfeits of the official Department of Homeland Security seal).

The keynote speaker at the opening day rally was U.S. Rep. Tom Tancredo of Colorado, the Republican who chairs the Congressional Immigration Reform Caucus.

Tancredo addressed a crowd of about 100 inside an auditorium not far from the OK Corral. Outside, a phalanx of private security police hired by the state stood between the hall’s entrance and about 40 anti-Minutemen protesters who banged on pots and pans and drums while a traditional Aztec dance group leapt and whirled to the cacophonous rhythm.

In late March, President George W. Bush had condemned the Minuteman Project at a joint press conference with Mexican President Vicente Fox. “I’m against vigilantes in the United States of America,” Bush said. “I’m for enforcing the law in a rational way.”

Tancredo said that Bush should be forced to write, “I’m sorry for calling you vigilantes,” on a blackboard one hundred times and then erase the chalk with his tongue.

“You are not vigilantes,” he roared. “You are heroes!”

Tancredo told the Minutemen that each of them stood for 100,000 like-minded Americans who couldn’t afford to make the trip. He applauded Gilchrist and Simcox as “two good men who understand we must never surrender our right as citizens to do our patriotic duty and defend our country ... and stop this invasion ourselves.”

Gilchrist is newly prominent on the anti-immigration front — he recently joined the California Coalition for Immigration Reform, a hate group whose leader routinely describes Mexicans as “savages.” But Simcox has been active since 2002, when he founded Civil Homeland Defense, a Tombstone-based vigilante militia that he brags has captured more than 5,000 Mexicans and Central Americans who entered the country without visas.

“These people don’t come here to work. They come here to rob and deal drugs,” Simcox told the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Intelligence Report in a 2003 interview. “We need the National Guard to clean up our cities and round them up.”

But that was the old Chris Simcox talking.

The old Simcox described Citizens Homeland Defense as “a committee of vigilantes,” and “a border patrol militia.” The new Simcox — the one interviewed for dozens of national tv news programs and major newspaper articles — characterized his new and larger outfit of citizen border patrollers as “more of a neighborhood watch program.”

The old Simcox said of Mexicans and Central American immigrants, “They have no problem slitting your throat and taking your money or selling drugs to your kids or raping your daughter, and they are evil people.” The new Simcox said he sympathizes with their plight and sees them as victims of their own government’s failed policies.

Gilchrist gave his sound bites an even more extreme makeover by frequently comparing himself and most of his volunteers to “white Martin Luther Kings” and the Minuteman Project to the civil rights movement. He and Simcox both declared in interview after interview that they had designed the Minuteman Project to “protect America from drug dealers and terrorists” as much as to catch undocumented immigrants.

For the most part, mainstream news coverage didn’t challenge these reinventions, even though Gilchrist’s militant rhetoric about immigrants “devouring and plundering our nation” was still up on the Minuteman Project’s web site, and Simcox’s statements had been published in his own newspaper and elsewhere.

Early this year, white supremacist and neo-Nazi web sites began openly recruiting for the Minuteman Project. In response, Gilchrist and Simcox announced that neo-Nazi skinheads and race warriors from organizations such as the National Alliance and Aryan Nations were specifically banned from participating. The two organizers said they were working with the FBI to carefully check the backgrounds of all potential Minuteman volunteers — only to have the FBI completely deny this was the case.

Gilchrist and Simcox then said they were personally checking out every potential volunteer using online databases. However, a computer crash wiped out the records of at least 75 pre-registered volunteers; perhaps as a result, during onsite registration at Tombstone, almost every person who showed up was issued a Minuteman Project badge and assigned to a watch post for the next day.

Gilchrist and Simcox also told news media prior to April 1 that the only volunteers who would be allowed to carry firearms would be those who had a concealed-carry handgun permit from their home states, an indication that they had passed at least a cursory background investigation. In fact, virtually no one was checked for permits.

While most of the Minuteman volunteers did not belong to racist groups, at least one member of Aryan Nations infiltrated the effort, and at least two members of the Phoenix chapter of the neo-Nazi National Alliance signed up as Minuteman volunteers. The two who identified themselves as members of the Alliance said four others from their group had arrived separately, to be less conspicuous. They said they intended to return in the fall and conduct small, roaming, National Alliance-only vigilante patrols, “when we can have a little more privacy,” as one Alliance member put it.

The day after the registration meltdown, the Minuteman Project sponsored a protest across the street from the Border Patrol’s headquarters in Naco, Ariz. It drew about 75 demonstrators, including the two National Alliance members, who sat quietly in camp chairs, wearing sunglasses and holding placards.

Their sign was decorated with a war-room graphic of arrows that represented armies marching north from Mexico and spreading throughout the United States.

“Invasion?” it asked. “What Invasion?”

This article was excerpted from Intelligence Report, a quarterly publication of the Southern Poverty Law Center.

Email this Article...

Email this Article...