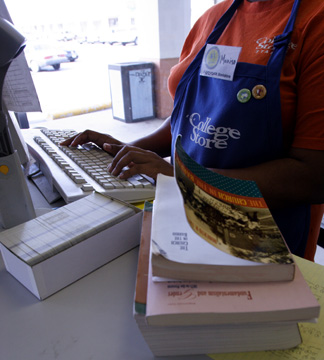

A College Store representative looks up the refund amount for a student \r\nwanting to sell back books.

A College Store representative looks up the refund amount for a student \r\nwanting to sell back books.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Buy-Back Blues

College students want textbook publishers to slow down on the updates.

By I’SHA GAINES

The student planted her flip-flops on the pavement of the college bookstore parking lot, fetched a volume from her trunk, and headed for the door, intent on what she figured was a mission impossible: trying to sell back the expensive textbook for a course she’d just finished.

“I hate it,” she said.

Minutes later she walked out of the store still holding the same book. “I just found out that the edition is changing,” she said in a not-so-surprised tone. No sale.

Melissa Frausto, a UT-Arlington student, had spent $90 on the book for an art history class. Plenty more students will take the same class next year, but the publisher had issued a new version of the text. Hers was now worthless.

More and more college students, engaging in the long-standing practice of selling back textbooks at the end of a semester, are running up against the same problem Frausto encountered this week: frequent “updating” of textbooks, often for seemingly trivial reasons, such as redesigns and updated graphics. The practice prevents students from being able to sell back those expensive texts — and means the next round of students will have to buy the new, not the cheaper used, version of the book.

“It’s a rip-off,” Frausto said.

It’s a cycle that can’t happen without the help of faculty members, who are often encouraged by book publishers to require the newer version of the book. When it’s the faculty member’s own book being used as a text, of course, the instructor has even more incentive to go along with the practice. One student talked about a new edition that a professor required for one course — even though the only difference from the last edition was a picture of George Bush replacing one of Bill Clinton. And a bookstore worker said that publishers sometimes talk faculty members into ordering special versions of books, customized just for that one course — and therefore of even less interest at the buy-back counter. With college textbooks now costing an average of $900 per semester for a full-time student and still rising, it’s an increasingly pricey problem for college students — especially since more students these days are paying their own way through school rather than being supported by parents.

In North Texas and elsewhere, students and their supporters are starting to fight back. Lauri Wiss, a sophomore at Brookhaven Community College in Farmers Branch, traveled to Austin this spring to testify in favor of a legislative proposal that could have relieved some of the textbook/pocketbook stress. State Rep. Marc Veasey of Fort Worth filed a bill to prevent publishers from updating college textbooks more often than once every three years. (Currently about a fourth of basic college texts are replaced by new editions each year.)

The bill didn’t make it through the legislative process this year, but it “was a great first effort,” Wiss said. A staffer said Veasey will probably file the bill again next session.

Predictably, publishers and booksellers opposed parts of Veasey’s bill. Cliff Ewert, vice president of public and campus relations for Follett Bookstores, said new editions are the prerogative of publishers. “They have the right to present new material, to make it more [likable to students through] new concepts and new facts that come along,” he said. “Given the dramatic pace of change in some academic disciplines, a title’s content may be current for only two or three years.” As a result, he said, a book’s buy-back period is limited. His company is a national textbook wholesaler that owns the UTA campus store.

UT-Arlington student Everett Hinson said he uses older books whenever he can just because he figures the publishers’ tactics are aimed at making a quick buck off students. Two years ago, for instance, he borrowed his dad’s 1980s version of a business law textbook, earned a B, and saved $150. “I brought my book to class and compared it to the other students’,” he said. “The information was the same, word-for-word ... My classmates were just paying for the re-design.”

Sarah Atwell, manager of The College Store, a used bookstore near UTA, said, professors are “so encouraged by the publishers” that they forget about the impact of textbook prices on students. For example, she said, a publisher may present instructors with research showing that they only teach from 23 chapters of a 25-chapter book, convincing them to order a version of the book customized for their lesson plan. “The professor will say, ‘I’m doing a big favor for the students,’” she said. But “the real book has 25 chapters. This eliminates the chance for buybacks.”

Students have other options for buying and reselling their books than the campus bookstore. Used bookstores will frequently buy textbooks regardless of whether new editions are out. And web-wise students now can frequently find used copies of books for sale on line.

However, Ewert said buying on line gives students no guarantee that their books will be delivered in time for class. And, he said, the loss of sales to the internet makes it harder for the bookstore to provide its benefits to students. “We provide value to the campus in many additional ways — from paying a percentage of sales to the institution, to employing people in the community (including students), to paying state taxes,” he said. “With the possible exception of taxes, the national online retailers do none of these things.”

At Brookhaven, instructors in the English department recognized that many students were not buying textbooks because of the cost. They adopted a system that uses the same textbook, plus an inexpensive supplement, for two successive courses. “We did that on purpose,” said Haven Abedi, an English professor. “It’s just a way to get twice the value out of the same book. We hope this will help students.”

Abedi said that because so many of today’s students are putting themselves through college, she is more sympathetic to those who struggle to pay for books. “That gets in the way of learning,” she said. “People have said to me before that significant changes are made and that’s why they update editions. [But] sometimes [those] changes do not warrant a whole new edition.”

Beverly Mooney, another UTA student, said she thinks publishers are exploiting students. “I thought $30 for a textbook was high when I went to school in the mid-70s,” she said. “But $130 seems extremely high now. Textbooks are priced at whatever the market can bear. Unfortunately that’s a very high price.”

Veasey said in an e-mail that, as Texas college tuition costs rise, “it has become more important to consider the other costs that students have to deal with and how we can best make education more affordable.”

Texas “is one of the largest textbook markets in the world,” he said, “and we can use that buying power to ensure that our students have affordable options.”

Email this Article...

Email this Article...