Guardiola in front of her fire-damaged home: ‘I was hoping for the American dream. ... But life isn’t like that.’

Guardiola in front of her fire-damaged home: ‘I was hoping for the American dream. ... But life isn’t like that.’

|

|

‘I didn’t want my kids growing up in a shelter, so I did what I had to do.’

|

Rice: ‘An awful lot [of United Way clients] are regular people who suddenly find themselves in over their heads.’

Rice: ‘An awful lot [of United Way clients] are regular people who suddenly find themselves in over their heads.’

|

|

‘Who recruits on a high school campus? The military, drug dealers, and credit card companies.’

|

Fulks: ‘Those companies push credit on people. ... I deal with the fallout.’

Fulks: ‘Those companies push credit on people. ... I deal with the fallout.’

|

Financially strapped people hit the pawn shops, but it’s not a strategy that helps for long.

Financially strapped people hit the pawn shops, but it’s not a strategy that helps for long.

|

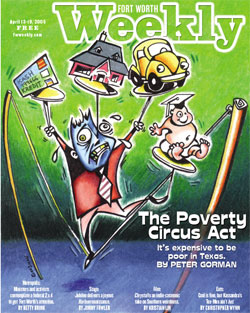

Cover Illustration by Mark Goodman

Cover Illustration by Mark Goodman

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

The Poverty Circus Act

It’s expensive to be poor in Texas.

By PETER GORMAN (Photos by Scott Latham)

The mentally challenged middle-aged man and his elderly mother had made it to the front of the line at the First Convenience Bank at a Fort Worth Wal-Mart on a Monday afternoon. Maybe you didn’t know you can bank at Wal-Mart, but there it is, in with the eyeglass repair shop and the photo studio. The man and his mom were talking to a young teller about bank fees.

The man had just opened the bank account a few days before and had his paycheck — $455 take-home for two weeks’ work — deposited there. The problem, it turned out, was that the check hadn’t been deposited until after 2 p.m. on Friday, which meant it wasn’t credited to the account until Monday night at midnight and wouldn’t be available until Tuesday at 9 a.m. Not realizing the delay, the man — obviously excited about the banking experience — had used his bank card 17 times between Friday evening and Monday — unknowingly ringing up another $29 overdraft charge each time. So when he went to the bank in person to take out more money, he found that not only was his whole paycheck gone, but he now owed the bank more than a hundred dollars beyond that. He couldn’t figure out what had happened.

“I didn’t spend that much,” he kept explaining, taking out his wallet and showing the teller receipts for gum, candy, a couple of dollars in gasoline, and a handful of other very minor expenses that didn’t total $100.

“Look,” the teller explained. “I told you when you opened that if you used the check protection it would cost $29 per use. It doesn’t matter how small it was. You used it 17 times, and that comes to $493. Your check was for $455, so you have no money left, and you owe the bank the difference as well as for your purchases.”

The man’s mother was near tears by this time. Fortunately, several irate customers waiting in line had overheard the conversation and demanded to speak to the branch manager, who agreed that perhaps the bank was out of line in this case and promised to remedy the situation.

Shortly thereafter First Convenience Bank raised its overdraft rates to $33. Why not? State banking regulators said banks can charge whatever overdraft fees they want. Such fees are common — and highly profitable — at the small banks that cater to the poor and middle class by offering checking accounts with automatic “overdraft protection” that’s supposed to help keep checks from bouncing.

Unfortunately, many poor people, living paycheck to paycheck, use the overdraft “protection” more like a short-term — and very high-interest — line of credit. “Some people use it like a regular loan,” said a teller at the same Wal-Mart branch bank where the opening story took place. “A lot of customers dip into it once or twice a month to cover a check or buy food.” How many of the customers? “Almost all of them,” said the teller, who asked that his name not be used. “And we have thousands of accounts.”

No one thinks paying $29 for the privilege of writing checks you can’t quite cover is a sound financial practice. But what are you going to do when your kids are hungry and you don’t get paid until Friday? It’s the kind of Hobson’s choice that poor people in North Texas and across the country are being forced to make more and more often. Welfare reforms instituted in 1996 are hitting home with a vengeance, housing programs are being cut back, and financial institutions — from banks to credit card companies — are finding new ways to add fees and jack up rates. An overhaul of bankruptcy laws now before Congress threatens to make even that extreme measure harder for most people to use. Local charities are trying to respond to needs that are growing far faster than their resources, and more and more middle-class jobs in this town — as in the U.S. economy in general — are being replaced by part-time work or service jobs or the kind of contract, project-by-project labor that carries few or no benefits. It all adds up to a slope that gets steeper and more slippery with each passing month.

As a release for Barbara Ehrenreich’s bestseller, Nickel and Dimed, noted, America has become a land of “a thousand desperate strategems for survival.”

Angela Guardiola is a strong 45-year-old Latina with dark eyes and a set jaw. She has a good job. Born in Lubbock, she’s lived in Fort Worth for most of her life. Her house is modest but just fine; better than that, it’s paid for. Her two children are grown and on their own. A short and bad second marriage, from which she’s been separated for nearly three years, is about to end in a non-acrimonious divorce. Life is good.

It hasn’t always been that way. “I’ve struggled most of my life to get where I am now,” she says with a Spanish accent that carries no trace of self-pity. Then she launches into a story that would have broken weaker men and women.

“In my first marriage I was hoping for the American Dream. You know, where you have to work, but everyone is healthy and happy. But life isn’t like that.” Her husband was a salesman, but he didn’t do very well, so Angela supported the family. “I didn’t mind, though. I was making about $14 an hour at a printing company,” good money in the late ’80s. They had two kids and bought a house. “But then my husband left, and after that I got laid off from my job. So now I had two kids and an $800 house payment and credit cards, no job, and no child support.” She found a job quickly, but it paid only $5 an hour, and pretty soon she found herself with the choice of keeping up either the car payments or the credit cards: “I kept the car and ruined my credit.” She applied for welfare and food stamps but was turned down for both because she owned a house and a car, despite neither of them being paid off. “They said I had to get rid of one or the other to get public assistance. Instead I worked two shifts a lot of the time, seven days a week.” At those wages, though, she still couldn’t make the house note, so after paying eight and a half years on a 15-year mortgage, she lost it. “I didn’t get anything from that. The bank said I didn’t have any equity in it.”

Her family is close, but none of them had house-payment kind of money to lend her. “That was 1993, and all my family was struggling, and my dad passed just about that time, so even my mom was struggling. I had nobody to borrow from to get through that,” she said. She was able to move into her mother’s home, though, and take over the $160-a-month mortgage payments. “That was a lifesaver,” she said. “I don’t know what I would have done if that house wasn’t there.” Not long after she moved into her mother’s house, however, she had to take over the raising of her sister’s two kids, because her sister could no longer support them, and the frequent double shifts became mandatory.

“I had the choice to either be with my kids and be homeless or work all the time and give them less time than they should have had with me. My son was 7 then, and my daughter was 15. I’d do one shift, then come home, and after they went to sleep I’d leave to go do the next shift. But I didn’t want my kids growing up in a shelter, so I did what I had to do.”

The double shifts and seven-day work weeks went on for several years. But Angela became a supervisor where she worked, and she met another man whom she married. With two incomes, the kids nearly grown, and the low mortgage on her mother’s house nearly paid off, she thought the tough times were through. They weren’t. The marriage lasted only a couple of years before he split, leaving her once again to carry the load.

“I got a job at a printing place again through a temp agency for $7.50 an hour, but they kept me on, and I’m up to $13.50 after three years, so I’m OK. But my credit is still bad, and when I had a fire in the house a couple of years ago, I couldn’t get a loan to repair the damage, so I had to keep living in it that way. I took a little money from each paycheck to slowly fix it.”

She looked for help everywhere she could think of. “I went to the Red Cross and the City of Fort Worth and the Housing Authority, and nobody could help because they said I make too much money. It doesn’t feel like too much money to me. Even with my kids grown, I still have to pay school tax, health insurance, disability, car insurance, a car payment of $310 a month on a 1998 car — it’s high because of my bad credit — and then eat and pay for gas. But they have their rules, and that’s that.”

It’s hard to imagine that Angela, raising four children on a $5-an-hour job, couldn’t get welfare or food stamps or that she couldn’t get help to repair the fire damage to her home. Unfortunately, on both the federal and city levels, ours is not a kinder and gentler society for poor people these days.

On the federal level, before the Welfare Reform Act of 1996, if Angela hadn’t owned both a car and a house, she might have been able to support herself, her mom, her kids, and her sister’s kids on welfare. Or she might have been able to cut back on work and become eligible for food stamps. But since January 1997, when changes to the welfare system (called Temporary Assistance for Needy Families or TANF in Texas) went into effect, she’s had no chance. According to census information, about 11.6 percent of Tarrant residents fall below the federal poverty line, which the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services sets at $16,090, for instance, for a family of three. But Texas rules are much more severe. To be eligible for TANF payments, that same family can have no more than $2,300 income annually. And what do they get if they qualify? A maximum benefit of $223 a month — “not exactly enough to live on” said Celia Hagert, the TANF expert at the Center for Public Policy Priorities, a nonprofit think tank based in Austin.

The TANF requirements and payments seem to have little to do with the real costs of raising a family. If you’re making $6.30 a day, TANF will add $7.60 to that to cover your housing, transportation, clothes, and everything you need in the kitchen and bathroom that food stamps won’t cover. And that’s if you get the maximum benefit. Texas has one of the lowest eligibility levels and provides the lowest benefits in the country. Applicants for food stamps find the help just as meager: A family of three with zero income is eligible for a maximum benefit of $393 per month, but the average benefit is $80 per person monthly. That comes to less than three bucks per day per person, enough for eggs and cheap hot dogs if you hold the mustard.

In Maria De la Cruz’ case, the “help” she got was worse than no help at all. Two years ago, the foundation of her Eastside home cracked, leading eventually to a leak in the roof. At 70, and living on a $600-a-month Social Security check, she had no money to fix it. She called her daughter Cathy for help. “I couldn’t help her at that moment because I was struggling to make ends meet myself,” Cathy told the Weekly. “So I tried to get city help.”

Cathy found out about a city agency that builds homes for poor people, but was told the waiting list was full just then. She contacted the Fort Worth Housing Authority, and they said they couldn’t help with the repairs either. “But we kept calling and calling and then finally, instead of sending out someone to help, they sent code compliance inspectors. They said the damage was too extensive by then and the repairs would be too expensive, so they condemned the house. It was her home for 25 years, and they just ordered it torn down and left my mom homeless.”

The city has no “emergency permanent housing” program, explained Vicky Mize of the United Way of Tarrant County, who works closely with city agencies on housing and other issues. “Apart from shelters, the city does have subsidized and low-cost apartments, and through the federal government offers Section 8 housing, but the waiting lists on those are often two to three years or longer,” she said. “And if the requests we get at the United Way for housing help are any indication, there are considerably more requests each year for the little that exists.”

Funding for the Section 8 voucher program was cut this year, and more cuts are expected for 2006.

With no savings and no home, De la Cruz was forced to quickly sell the property her home had sat on. She got $4,000 for a piece of land worth several times that. With that she was able to get an apartment, but moving costs and security deposits ate into her tiny nest egg, and in a matter of months the $500 rent finished the rest.

“When that little bit was gone, how was she going to pay her rent and utilities on her $600 a month?” asked Cathy. “She couldn’t, and the stress got too much. She had a heart attack in November.”

Fortunately Medicaid took care of the medical bills, and De la Cruz was able to move in with her daughter. Because the city has a long waiting list for those who need transportation to doctors, however, Cathy has had to take off several days a month since then to get her mother to her medical appointments. “I can’t afford to lose that pay,” she said, “but that’s life.”

When a major financial blow — like the demolition of a home — dumps a household in the path of financial disaster, people often need help in a hurry. The cold reality is, however, that major assistance programs seldom kick in quickly — if they kick in at all. And so people are forced into the frantic maneuvers that keep them one step ahead of the flood.

Celia Hagert said the Center for Public Policy Priorities recently spent four months following several families who found themselves a day late and a dollar short, to see how they coped. “What we found was that they were all involved in this fantastic and complex juggling act. What bill absolutely had to get paid? What bill could they get an extension on? Did they have anything they could pawn? Was it worth it to get a payday loan from a check-cashing house? Could they get more credit? They’d sell what they could, have garage sales, and basically just juggle for as long as they could, hoping that the overtime would come back, the raise would come through, a new job would open up.”

Most of those desperate measures work once or twice — and at great cost. Pawning your possessions or selling them at garage sales brings in pennies on the dollar of what things are actually worth. Paying one bill late and letting another one slide results in late fees. Payday loans from Ace Check Cashing, which has sites all over Fort Worth, might sound reasonable—you pay $17.64 in interest on $100 for two weeks or less — but that comes to about 460 percent interest annually. If you can’t pay off a short-term loan in two weeks, and if it was for, say, $400, you’ll find that the interest is $137.28 at the end of a month. So if you do make some extra overtime that month, instead of using it to get ahead, all of a sudden it goes to keep the lights turned on and to pay the late fees on the overdue loan.

And Ace isn’t the worst. Usury laws in Texas are so weak that loan companies can charge almost any rate they want. Payday loans from internet sites routinely charge $250 interest on a $600 loan for a week or less — figures that would make New York City loansharks blush.

“The problem starts with people,” said Coleman Cassel, CEO of Startovertoday.com, a nationwide “financial solutions” company. “Most Americans spend about 110 percent of what they earn” — his opinion, not a hard figure. “Which means they don’t have savings for when things go wrong — and they will go wrong sooner or later.” Cassel admits that by the time people reach him, they generally have too much debt. “People don’t really understand credit,” he said. “You shouldn’t even have credit cards unless you can pay them all off completely before the end of the grace period. If you’re using them because you’re strapped, you’re already in trouble. I’ve seen people make washer and dryer purchases that cost two and three times their original price and they’re still nowhere near paid off. That is being poor. Better to wait on that purchase ’til you can buy it, pay for it, and be done with it. But that’s not how people think.”

Cassel sees credit card lending practices and Americans’ overspending as the one-two punch that lands many people in hot water. “Look at your credit cards. Let’s say you’re smart and have managed to get your cards all locked in at reasonable rates, say from 5.9 percent to 9 percent. Seems handleable. But then credit card companies sometimes sell your account to other companies with whom you are not locked in, so you get a bill and suddenly see that it’s from a company you never heard of and that 5.9 percent rate is 24.9 percent. Nothing you can do about it.”

Moreover, he said, it’s a regular practice of credit card companies to shorten their grace period. What might have started out as a 30-day grace period before interest sets in suddenly gets changed to a 20-day grace period. Notice of the change would have been in some small print that came with your regular bill — print the credit card company knows you will not read. “They’re counting on you missing it. And if you’re like most Americans, waiting ’til the last minute to pay the bill ... well, you just got slammed. Because you now paid late. And paying late opens you up to the Universal Default Clause — or what I call the universal slam.”

The Universal Default Clause, said Cassel, is a tiny clause that credit card companies have been inserting in their initial agreements recently. It states that if you are ever late with a payment on one card, you can be viewed as having been late with all your cards, and so your interest rates can be changed on every card you have. “Heck, in Texas, they [the rates] can rise to anything the companies want,” he said.

He paused to laugh. “I’m not just talking about the late fees — and some of them are up to $49. I’m talking about a Chase card one of my clients brought in today with an interest rate of 49.99 percent. Imagine having your interest — based on being slammed because you were late on a card one month — jump from 5.9 percent to 49.99 percent overnight. They just buried you. And there’s nothing illegal about that.”

Cassel also said that the percentage of people defaulting on credit card bills is “way up in the last couple of years, no matter what you read about the recovering economy.” And so the companies have taken to calling neighbors to ask them to try to collect their bills. “Can you imagine someone calling your neighbor or your work and telling them you’re a deadbeat and can they try to get a payment out of you? How that is not illegal I don’t know, but it’s not. And these companies make billions off people.”

In fact, Cassel said, most of his clients are not deadbeats. “They just simply cannot support those fees. Nobody can pay 24 percent interest to anyone when you’re just getting by to begin with.”

By the time they reach Cassel, most clients are near the end of their rope, and what they need is a way out. For many, that way is debt negotiation, in which you or someone like Cassel calls your credit card companies, cancels your cards, and tries to make a deal. “We ask the company if they’ll take maybe 50 cents on a dollar and call it even,” he said. It’s a technique that will ruin your credit, though by that point it’s probably already ruined. You also end up with no credit card — a painful but healthy development in the long term.

“We’re getting more and more people who are making $70,000 a year who just can’t make it anymore,” Cassel said. “If only they’d taken a basic economics course at some point, learned to put away 10 percent of that paycheck no matter what. Never bought anything except a house or car that they couldn’t pay off in a month.” While they’re in a financially healthy mode, he said, workers should buy a series of certificates of deposit, each valued at what it takes that person to live on for a month, set up to mature one a month for six months. With that done, he said, “you have half a year to get through that divorce or job loss.”

The next step for many people after debt negotiation is bankruptcy. It’s the final stigma of failure for most people. But it happens to a lot of people. According to the American Bankruptcy Institute, more than 1.6 million individual Americans filed last year, about a 20 percent increase since 1999. And those who filed were not primarily people in poverty; they were mostly from the middle class.

“Our clients are bankers, teachers, military men, people from middle and upper management,” said Cole Fulks, a Fort Worth bankruptcy attorney. “I’ve been doing bankruptcies for more than 10 years now and have seen a sizable increase in the number of filings by regular working people in the last three to four years.”

The three primary reasons people end up in bankruptcy court, he said, are layoffs, medical bills, and divorce. But Fulks also puts some of the blame on lending institutions and “predatory lending practices.”

“These companies push credit on people. Who recruits on a high school campus? The military, drug dealers, and credit card companies. That should tell you something. They offer good loan rates, then change them, and suddenly people are stuck. I deal with the fallout.”

The bankruptcy system was created in the United States because Americans abhorred the British debtors prison system. In theory, bankruptcy allows you, when pressed to the wall by debt, to get a chance to start over.

Unfortunately, changes in the bankruptcy laws now in front of Congress — lobbied for by credit lending firms — would limit a person’s right to discharge his debts. “What you’re seeing in the legislature is the attempt to deny a person’s ability to get relief from predatory debt,” Fulks said. “The new laws will push more people into Chapter 13 bankruptcy, which is a repayment plan, rather than debt liquidation that you have with Chapter 7 bankruptcy.

“What it really means is that if you’re poor, for whatever reason, it’s going to be harder to get back on your feet. But then that’s what this society does with poor people at every turn: Even a loaf of bread and a gallon of gas cost more in a poor neighborhood than in a nice middle-class one.”

Debbie Kratky, who works for Texas Workforce Solutions in Fort Worth, sees every day how hard it is for people to get back on their feet financially. “There are an awful lot more people than services. And there are an awful lot of poor people who’ve been middle class all their lives, who, when one thing or another happens, suddenly find themselves poor. The problem is getting back out once you’ve fallen into that hole.”

Or as Angela Guardiola puts it, “Once you’re down, you find out that poor people pay more for everything, which makes it doubly hard to climb up again.”

How hard? Cars are a good example. If two people take out identical $11,000 car loans, and one has a good credit score, he or she may get financing at 4 percent. The second person, with shaky credit, might have to pay 12.9 percent. That’s a difference of $50 a month, or about $3,000 on a five-year loan.

The same holds true for store credit cards and major credit cards. Those with the least have to pay more to assure the lender he’ll get a return on his money before the shaky creditor defaults. Even car insurance rates go up if your credit is bad.

God forbid that all those higher charges lead you to bounce a check. You’ll probably get hit with a $25 fee from the person you wrote the check to and another $25 from your bank — or maybe $33, if you bank at Wal-Mart.

When the Weekly called more than a dozen banks around Texas, none provided an explanation as to what costs such fees were needed to cover. Simply put, the fees are a profit center for the banks, and they can set whatever overdraft rates they want.

Banks that cater to a poorer clientele generate more income than larger banks that make their money on legitimate loans. Is the extra income due to overdraft fees? The banks don’t have to tell. “Fees are always incorporated with loan interest earnings,” said an analyst at Standard and Poor. “Ever since banks started giving out the automatic overdraft protection, they guard that income from everyone very jealously. And if we can’t get it, there’s no way to get it.”

Poor, of course, is a relative term, and one that most people don’t want to apply to themselves. But in the first decade of this new millennium, there can be few Americans left who believe that their industries, their jobs, and their creature comforts are secure. From the burst of the dot.com bubble to the economic disaster that followed the 9/11 tragedies, to the speeded-up exportation of American jobs to other countries — the body blows to workers in this country have come fast and furious. In Fort Worth, all five of the big blue-collar employers — American Airlines, Lockheed, Bell Helicopter, General Motors, and General Dynamics — have undergone “restructuring” in the last few years, changing the work status of tens of thousands in Tarrant County from full-time employees with good benefits to project employees with fewer, if any, benefits — and with unpaid time off between projects.

There is unemployment insurance, of course, but that tops out at $336 weekly for anyone who earned $33,600 in the previous 12 months — not exactly enough to keep up a modest $800 mortgage, make the car, utility, and insurance payments, and still feed the kids. Add a divorce or a serious illness — especially if health insurance went out the window with the full-time job — and securely middle-class families can find that the SUV they were traveling in on Easy Street was equipped with ejector seats.

Then there are permanent layoffs. According to Limous Walker, with Texas Workforce Solutions, which tries to find work for the unemployed and underemployed, Tarrant County lost 4,965 full-time jobs last year alone. “Office Max lost 293 jobs to a closure,” said Walker, “and Atlantic Southeast lost 1,200. Lockheed lost several hundred. Osteopathic Medical Center dropped 1,188 — though some of those were able to find other work in the medical industry fairly quickly.” And those are just the ones his agency knows about — many layoffs don’t get reported, nor do changes at companies that cut back on overtime and part-time jobs.

One indicator of how many people are falling into the “poor” category, at least temporarily, is the fast-growing number of calls for assistance to the United Way. Between 2002 and 2004, for instance, the number of calls to the Tarrant County agency just for help with utility bills more than doubled. Housing assistance calls rose 51 percent over the same two-year period.

Vicky Mize pointed out that few of the callers are jobless. “The majority of our callers have some employment, but their job just doesn’t pay what it used to or it’s a new job which simply can’t make ends meet,” she said.

Her United Way colleague, Ann Rice, agreed. “A lot of our calls come from people who have underlying problems, like alcohol or drug abuse or domestic violence issues. But an awful lot are regular people who suddenly find themselves in the situation of being in over their heads. It might be divorce, work, or health issues, but something has changed and they’re not able to make it any longer without help.”

In Jim Lively’s case it was a medical problem that drove his finances off the road. Lively, 51, has a good job in manufacturing, and his wife was earning nearly $50,000 in an administrative position. They had three kids, all grown. And Lively didn’t even have any credit cards. “I maxed them out 22 years ago and had to pay them off. So I got rid of them,” he said. It should have been Easy Street. There was a college loan to pay off, and there were house and car and truck and insurance payments and even an IRS bill, but nothing the couple couldn’t handle with two incomes.

Then, last year, Lively’s wife had a heart attack, and two of his kids, one with a baby, moved back home. Suddenly Lively’s job was supporting everything and everyone, including paying the difference between his wife’s medical bills and what insurance covered. “That fast, things changed. I was lucky in that I could refinance the house to eliminate a couple of debts, and I still have my overtime, but it’s paycheck to paycheck. You love your kids and they need help, you help. Got the grandbaby, she needs formula. My 19-year-old is an eating machine. Thank goodness for Wal-Mart. Without my wife’s pay, we just got nailed. I got paid today and worked 16 hours overtime this pay period, and after the bills I’ll have $40 to get by for the next two weeks. That’s it.”

Lively’s wife went back to work recently, but rather than the high-paying, high-stress office job, she’s working part-time at a farmer’s market. “That’s fine by me,” Lively said. “I’d rather be poor and healthy than have her sick.”

For the rest of us, it’s cross your fingers things don’t go sour. As Angela Guardiola says, it’s “paycheck to paycheck and don’t get sick. It’s all you can do when you’re poor.”

Email this Article...

Email this Article...