Lt. Jon Grady as pictured in a recent issue of the Signal 50 newsletter.

Lt. Jon Grady as pictured in a recent issue of the Signal 50 newsletter.

|

|

‘I’ve never seen a cop so widely\r\ndisrespected by his own officers.’

|

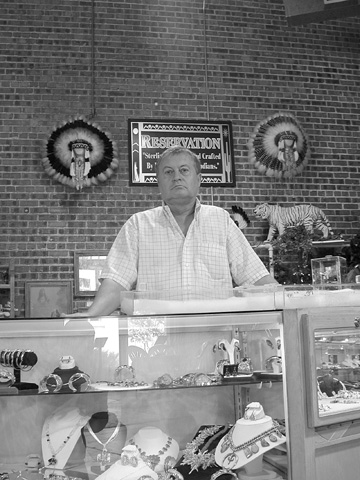

Stockyards businessman Fred Flippin faced the wrath of Grady.

Stockyards businessman Fred Flippin faced the wrath of Grady.

|

|

‘You may have a person who feels like every time it rains, it’s Lt. Grady’s fault,’ he said.

|

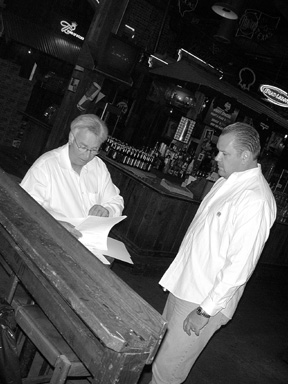

Neon Moon owner Darren Rhea (right) shows Costanza a copy of the lawsuit against Grady.

Neon Moon owner Darren Rhea (right) shows Costanza a copy of the lawsuit against Grady.

|

Beer trucks parked while drivers make quick deliveries are frequently ticketed.

Beer trucks parked while drivers make quick deliveries are frequently ticketed.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Officer Un-friendly

Stockyards businessmen don’t like the way\r\none cop is taming their “town.”

By JEFF PRINCE

The world’s largest honkytonk was quiet and still; early morning weekdays are hardly its prime time. A lone pickup truck made a dot on the sprawling public parking lot at Billy Bob’s Texas — perhaps someone too drunk to drive home the previous night, or maybe someone lucky in love. The employee parking lot, however, was crowded, and amid its rows sat several police cars and civilian city vehicles.

Inside the cavernous building, a few workers cleaned windows and swept floors, occasionally stepping around the dozen or so police officers and city employees milling outside a VIP room. A meeting was about to begin, prompted by complaints from Mike Costanza, part-owner and property manager of the Rodeo Plaza building (the canary yellow mini-mall next to Billy Bob’s in the Stockyards).

One of his complaints involved parking tickets written by Police Lt. Jon Grady, possibly the only lieutenant in Fort Worth police history to make a habit of writing parking tickets. The Stockyards is sleepy and empty on most weekday mornings, but Grady sometimes shows up to leave tickets on beer trucks while the driver is making deliveries, or on service trucks while the driver is making repairs, or on business owners’ vehicles while they are parked in front of their own shops.

“Some of the things the city does are not right,” Costanza said. “When you’ve got suppliers and delivery and service people out there, we need to make some kind of compromise. There is some common sense that needs to be used.”

June’s stormy winds wreaked havoc citywide, and the Stockyards district was no exception. Store owners discovered damages to their roofs and air conditioners. On the morning of June 15, numerous vehicles were parked in 20-minute parking zones or tow-away zones along Rodeo Plaza as contractors worked on repairs. Before long, a ticket bearing Grady’s name adorned each windshield. He had already told business owners that service trucks and such would require special permits to park in Rodeo Plaza, a short dead-end street that runs north from Exchange, past the Cowtown Coliseum, and ends at Billy Bob’s. The city is trying to discourage traffic and convert it into a pedestrian area and has posted parking signs on almost every light pole. Some forbid parking altogether, some allow 20 minutes for deliveries, and some delineate fire lanes.

“With everything that has occurred with storms, there are still the proper procedures,” Grady said later.

Costanza, his attorney, and a couple of his roofers were among those getting ticketed. “I didn’t like it, but I accepted it,” Costanza said.

Also cited were several vehicles driven by air conditioning repairmen working at Billy Bob’s. Days later, Costanza heard that someone at Billy Bob’s had complained to police, and an officer had picked up and rescinded those citations. Costanza wanted his tickets rescinded as well, but Grady refused. An infuriated Costanza contacted police and asked to speak to Chief Ralph Mendoza. The chief was out of town, but Costanza left a pointed message requesting a meeting.

Later that afternoon, Grady grudgingly agreed to rescind the tickets. Deputy Chief Mike Manning quickly arranged a meeting with Costanza, Billy Bob’s manager Billy Minick, Cowtown Coliseum general manager Hub Baker, and city employees from the fire, community service, and city manager’s departments, along with a half-dozen police officers, including Grady.

Costanza invited a Fort Worth Weekly reporter, but Grady insisted the meeting remain private. The Weekly called Grady to ask why. “We want to meet with the property owners so we can find out what the problems are and address them,” he said. “It’s not like we think you’re going to create havoc, but we’ve asked that just the key players be there. If everyone brings somebody along, before long you have a whole room full of people, and nothing gets settled or addressed.”

The Weekly showed up anyway. Prior to the meeting, the reporter asked Grady again for permission to attend. Grady was standing with a few other police officers, some of whom chuckled to see the dour lieutenant being put on the spot. Grady’s jowly face wasn’t smiling, and the six-foot-tall New York native displayed the abrupt nature that some officers say contributes to his clashes with the Stockyards crowd. “It’s not open to the public,” he said. After a few moments of debate with the reporter, Grady deferred the decision to Deputy Chief Manning, who said the Weekly would not be allowed in the meeting but could ask questions afterward.

The meeting was the outgrowth, in part, of the police department’s ongoing effort to change the Stockyards from party central to — in some eyes — a happy-sappy plasticized family fun destination. It’s a sometimes-painful change that helps some businesses and leaves other businesses and groups feeling left in the dirt. Motorcycle enthusiasts who once flocked to the areas for Sunday fun have been shooed away. Police have cracked down on fights and public intoxication — at times, according to some, gathering up innocent bystanders and scaring off bar patrons.

The meeting addressed some problems. The city manager’s office agreed to develop standard operating procedures regarding parking and deliveries at Rodeo Plaza. As the meeting let out, the Weekly tried to photograph Grady but he was an artful dodger. “I’d rather have a gun pointed at me than a camera,” he said, keeping his face turned away from the camera.

Despite the meeting, Stockyards folks doubt they have heard the last of Grady. He has become a lightning rod for controversy, characterized as an arrogant, no-nonsense cop with little personality and a lot of talent for clashing with people — including his brothers and sisters in blue.

“Grady doesn’t have good rapport with the community,” said a longtime Fort Worth police officer who requested anonymity for fear of reprisals. “If he decides he doesn’t like you, he will nickel-and-dime you to death. He is going to tell you what to do, and if you don’t like it, that’s tough. Grady is the kind of guy that it’s his way or the highway. He thinks he is bulletproof.” Officers also suspect Grady is Mendoza’s ally, sent to disrupt the Fort Worth Police Officers Association, create disharmony, and weaken its power base.

One bar owner in June decided to do more than grumble. Darren Rhea, owner of the Neon Moon Saloon, filed a lawsuit against Grady and took the unusual step of requesting a restraining order. “In 10 years down there I’ve never had a problem with cops, but Lt. Grady is trying to break me,” Rhea said. “All we’re trying to do is make a living. As hard as we’re working to pull people down here, he’s working to push them out.”

Property owners and police officers alike have offered him congratulations and support for filing suit, Rhea said. “I’ve never seen a cop so widely disrespected by his own officers.”

The top brass, however, stand behind their man, characterizing Grady as a devoted cop with a good record. “Jon enforces the rules,” Manning said. “He makes mistakes like everyone does. He’s made very few as far as enforcement goes. I have looked at Jon’s activities closely. The mistakes he’s made looked like mistakes of the heart. He has not been involved in any vendetta against any individuals.”

Eventually, a judge will decide whether that premise holds up in court. But some people have already reached their own verdict. As far as they’re concerned, he’s a cop spoiling for trouble and in need of an attitude adjustment.

The police association’s top guy wasn’t exactly gloating, but a certain air of exoneration tinged his demeanor earlier this month. “I’m quite pleased,” he said. “Nobody’s stealing. Nobody’s embezzling. We never thought any of that stuff was going on.”

An independent audit gave a clean bill of health to the financial statements and accounting practices of the Fort Worth Police Officers Association. President Lee Jackson would share the report that evening with his fellow cops at their regular monthly meeting. “The audit came out as good as I thought it would,” he said. “It cost a lot of money, but I’m glad it was done.”

Two months earlier, members approved the $10,500 audit after Grady questioned the leadership’s spending and accounting practices and sent letters of complaint to the Internal Revenue Service and Texas attorney general. Despite Grady’s 22 years on the Fort Worth force, his fellow officers don’t recall seeing much of him at meetings until this year, when he began inquiring about the group’s finances.

According to one officer who requested anonymity, Grady used the city’s e-mail system to “create rumors” about the police association, an action that drew no disciplinary action, as it might have for others. “He’s connected with Mendoza,” the officer said. “It’s just stirring the pot. He thinks he raises his esteem in the eyes of the chief every time he dicks with the association. That’s just Jon Grady.”

Manning, however, said Grady indeed was counseled for “sending an e-mail about POA [police officers association] business that was determined to not be an appropriate use of the e-mail system.”

Jackson was careful not to criticize Grady, other than to say, “I’ve known him a long time, and I can’t figure out the guy.” By nature, cops hesitate to criticize other cops in public, especially to the news media. But the current edition of the association’s monthly newsletter, Signal 50, reveals the festering rancor. Treasurer Sam Livingston wrote a column that answered, point by point, 24 different criticisms leveled by Grady. For instance, Grady wrote, “some general members of the POA have been fronted money for trips and have failed to pay back the money.” Livingston countered with, “NOT TRUE. Money was never fronted to general members.”

Grady questioned the POA’s practice of paying $600 a month to board member D.J. Scott to clean the association’s building on Collier Street, just west of downtown. Livingston responded that Scott submitted a bid, which the board deemed comparable to other competing bids.

The tit-for-tat continued for three pages.

Scott responded in his own full-page column titled “The Me versus the We.” The column, about a “nasty virus” that has “infiltrated our family” is clearly aimed at Grady.

Jackson’s column, entitled “From the President,” described how Grady’s motion to have a three-year audit was voted down 77 to 21, and said that the audit would have cost the association $30,000 to $35,000. “Since then Jon has circulated another letter saying that he is ‘just asking for the truth,’” Jackson wrote. “Well, Jon, why don’t you start by telling the truth? Jon wants to prove that your POA has been negligent with POA funds for a three-year period so that he can get his dues back and start his own supervisors’ POA.”

Jackson’s column accused Grady of misusing proxy votes on the motion and refusing to supply the association with copies of the proxies. And in a final jab, Signal 50 published two photos side by side. In one, Jackson is standing straight and tall, gesturing dramatically with his hand, his eyes wide and impassioned as he is speaking with determination. Beside that photo is one of Grady, who is shown slump-shouldered with arms crossed, his eyes and head cast slightly downward. The placement of the photos makes Jackson appear to be chastising a pouting Grady.

Grady said he has no plans to form a police association for supervisors only. “The only thing I have ever suggested is that if [board members] can’t answer this stuff, another police officers’ association could be formed,” he said. “There are certain people that don’t like the way the current Fort Worth Police Officers Association is doing business. Some of the money that’s spent, I’m not sure they know why it was spent.”

Police officers speaking off the record describe Grady as an infiltrator for Mendoza, attempting to cause division in the ranks. The association has clashed with Mendoza in recent months over the establishment of a light-duty policy that would allow disabled police officers to remain in desk jobs. The city council began considering the policy after undercover narcotics officer Lisa Ramsey was shot and paralyzed during a drug bust last year.

Mendoza has said he opposes such a policy (he axed a similar policy shortly after taking over as chief in 2000, citing poor management of the program). The debate became heated, and police officers have grown increasingly impatient with their chief. A Signal 50 editorial lamented that “while this head in the sand attitude from the administration has not been unexpected, it should sadden all of us that our chief is still unwilling to support his own officers, the very backbone of the Fort Worth Police Department, in what could be the hour of their greatest need.”

In an obvious reference to Grady, the same editorial said, “What is even more disturbing is that some of our officers, most of them of the higher ranks and little more than sycophants to the chief’s office, are actively working behind the scenes to try to derail the efforts of the FWPOA ... to create a new light-duty policy to help our officers. They have tried to draw attention away from our effort by attacking the reputations of individual board members with lies, rumor, and innuendo.”

Rhea said he has been told by police officers that Grady does what he wants with little retribution because of a friendly, back-scratching relationship with Mendoza. They said Grady is willing to be the fall guy in the police department’s attempt to transform the Stockyards, and he is prepared to create turmoil at the police association to benefit Mendoza. The chief in turn is willing to turn his head to complaints against Grady, who helps supervise a police unit that patrols the Stockyards and North Side.

Deputy Chief Manning said no police officer, including Grady, is untouchable. “That’s a ridiculous accusation,” he said. “He’s worked for me for the past two years. I can see no evidence that he is protected by the chief of police or by anyone else. When he screws up, I get the phone calls from the chief just like I get phone calls when anyone else in my command screws up.”

Mendoza did not return phone calls seeking comment.

Fred Flippin, 59, and his wife, Victoria, own Victoria’s Sterling Silver in Rodeo Plaza. Several months ago, Flippin, who has a medical condition that causes him back pain, parked his truck near the front door to unload inventory at about 9:30 a.m. on a weekday. It’s a typically quiet time at the Stockyards, especially at the Rodeo Plaza building, which doesn’t open for business until 10. Flippin returned to move his truck and found Grady ticketing his vehicle. “He had already written a ticket and put it on the windshield,” Flippin said. “I approached him and told him what I was doing. I was very nice to him. I respect our police force very much. He said, ‘You’re in a no-parking zone, and if I catch you here again, next time I’ll have your vehicle towed.’ I tried to talk to him about the ticket, and he wouldn’t even talk about it. The ticket cost me $100.”

The dispute didn’t end there. “I was trying to talk to him, and I laid the ticket on the hood, and it blew off, and [Grady] threatened me with littering if I didn’t pick it up immediately,” Flippin said. “He was real arrogant about it. By this time I was in a pretty hot discussion with him because I felt he should give me some consideration about the ticket. I explained we had been in the Stockyards a long time as business people, and we didn’t just park there; we only did it to unload our supplies in the morning. That same day my wife and I made several phone calls talking to different officers with the police department, and they more or less told us that’s the way he is. They said they get a lot of complaints about him.”

Billy Bob’s general manager Marty Travis said he has utmost respect for police, and he hesitated to talk about Grady. “As I talk to other people around, it seems like he’s a very stern person who is very rules-driven and by the book,” he said. “The other officers are usually more — I have to choose my words here — the other officers here are usually ... more understanding.”

Years of clashes led Rhea to file his lawsuit in June, accusing Grady of harassment and attempting to ruin his business. Rhea’s attorney, Terry Vernon, said the harassment of Rhea and Neon Moon employees and customers amounts to a vendetta. “Grady is trying to put him out of business,” Vernon said. “So far his chain of command is not doing anything to stop him.”

Grady disputes the claims and characterizes himself as the one unjustly accused. “You may have a person who feels like every time it rains, it’s Lt. Grady’s fault,” he said.

A look at Grady’s personnel file, or at least the portion released by police, shows excellent evaluations and plenty of praise for actions in the line of duty, such as preventing a woman from committing suicide, apprehending a knife-wielding robber after a foot chase, apprehending a hit-and-run driver, helping to capture murder suspects, and many other courageous acts. Former Police Chief Thomas Windham promoted Grady to sergeant in 1990. Within a few years, Grady was assigned to a unit under the supervision of then-Deputy Chief Ralph Mendoza. He was promoted to lieutenant in 1995 and began working in vice in 2000, which included spending time in the Stockyards.

Grady’s evaluations have been excellent for 20 years, although there were disciplinary actions in the early part of his career. A year after Grady joined the force, former Chief H.F. Hopkins suspended him for a day in 1983 after he was twice involved in minor traffic accidents. Two years later Hopkins suspended him for 10 days for a series of separate infractions, including “visiting with a young white female at her residence” while on duty, lying about the amount of time he spent on a lunch break, failing to complete an accident report, and failing to search a prisoner. After those suspensions, his personnel file paints a picture of a hard-working and dedicated cop with no further complaints on record.

That’s news to Rhea. On July 3, 2003, he complained to police after numerous clashes with Grady, culminating in the police closing down the Neon Moon early one night without providing justification. Rhea requested an internal investigation and then waited. After a month, Rhea’s attorney Vernon sent a letter to Mendoza complaining that “there has been no attempt by Internal Affairs to contact my client or the witnesses to the event.” On Aug. 26, Vernon sent a similar letter to Internal Affairs and included additional complaints against Grady for writing parking tickets to Neon Moon’s delivery truck drivers and to Rhea while their vehicles were parked in 20-minute parking zones, even though the vehicles hadn’t violated the time limits. “The only conclusion is that this is blatant retaliation by Lt. Grady because my client has filed a complaint against his prior activities of interfering with my client’s business,” Vernon wrote.

He received no reply from police.

Finally, after more inquiries, Rhea received a letter from Mendoza on Nov. 21, almost six months after the initial complaint. “After careful examination and evaluation of evidence, it has been determined by the officer’s chain of command that the officer’s actions were not within the departmental guidelines,” Mendoza wrote. The letter said that Grady and a sergeant were “disciplined for their actions.”

That didn’t deter Grady, who returned with a vengeance, Rhea said, rattling off a list of things the lieutenant did afterward: ticketing delivery vehicles even when they were in 20-minute loading zones, telling a Neon Moon employee who was sweeping a sidewalk to go back inside the bar or be arrested for loitering, parking outside the bar and shining a spotlight into the entranceway, ordering bar checks that seemed designed to run off customers, and so on. Rhea said patrol officers told him that Grady had given them instructions to “lean on” the bar. “I won this internal affairs investigation — I want to know what that meant because the son of a bitch was back down here the next weekend,” he said. “I don’t think they disciplined him at all.”

Rhea is right; Grady wasn’t disciplined. A public information request submitted by the Weekly sought the lieutenant’s complete file, but some documents were withheld. An accompanying note from the city attorney’s office said documents regarding misconduct “may not be placed in the person’s personnel file if the employing department determines that there is insufficient evidence to sustain the charge of misconduct.” If the charge of misconduct wasn’t proven, the city didn’t have to release any records. Yet Mendoza’s letter clearly stated that Grady had been disciplined, so why wasn’t the letter provided as public records?

Deputy Chief Manning said the complaint against Grady was not substantiated, and that the lieutenant merely received a “commander’s admonishment” for “an internal policy violation.” Prior to their bar check at Neon Moon, Grady had briefed police officers but failed to properly instruct them regarding whether to close down the bar, Manning said. Officers closed the bar early, but Grady wasn’t there. “It was my determination that Jon should have made his instructions clearer during the briefing that had occurred earlier in the night,” Manning said. “The sergeant was from a different unit and wasn’t up on vice issues, such as how some bars are allowed to stay open after 2 a.m. The sergeant did not talk to Jon during the early closing. She called him but didn’t get ahold of him.”

Police had shut down the bar early but hadn’t necessarily been told to do so by Grady. “The complaint as alleged was not sustained,” Manning said. The letter from Mendoza was simply a form letter stating that an investigation had occurred, he said.

The police department, at Manning’s urging, decided to rein in the Stockyards two years ago. Too many resources were being used to control the traffic and revelry. Police brass hoped that proactive enforcement would quell the carousing, reduce the demands on police, improve safety, and allow the department to “get control of our budget,” Manning said.

“The Stockyards has always been considered a wild and wide open area,” he said.

Grady is a visible presence and a frontline leader in taming the Stockyards, and so he is naturally receiving much of the heat. “A lot of things have gone on, but times change,” Grady said. “Now we are more conscious about public safety.”

Rhea, however, said that Grady’s proactive enforcement at Neon Moon is more akin to harassment prompted by a personal vendetta. Grady and Rhea first locked horns more than three years ago after Rhea bought the Longhorn Saloon a block away on West Exchange. Rhea had yet to open and was cleaning one day when Grady walked in wearing plain clothes and asked Rhea if he intended to allow minors inside. When Rhea asked him who he was, the man introduced himself as a police lieutenant. Rhea said he would allow minors inside but would use a bracelet system to ensure they didn’t drink alcoholic beverages. Grady was skeptical.

“That’s what got this whole thing started; that was the beginning of the Grady era,” Rhea said

When the Longhorn opened, Grady returned and told Rhea that he should hire four off-duty police officers, at $30 an hour each, to work security in the bar. Rhea said the number of officers seemed excessive but that he agreed in an effort to get along. Rhea was paying more than $300 a night for off -duty cops, but noticed that some would flirt with women while being aggressive and impatient with men. Rhea said his business began suffering. After an officer told a male patron to tuck in his shirt, Rhea said he stopped employing the off-duty officers. That’s when the harassment started. Rhea said the Longhorn had been raking in $100,000 a month when he purchased it. “Grady started the wheel turning that put me out of business at the Longhorn,” he said. “The police presence deleted the crowd to where the business was insolvent.”

Rhea closed the Longhorn and focused on Neon Moon on East Exchange, but Grady’s harassment continued there, he said. Grady wrote parking tickets outside Neon Moon, even to delivery trucks stopped for short periods to unload beer. About a dozen police officers showed up on a Saturday night in June with a COPS television film crew, entered Neon Moon, and questioned patrons in a search of minors drinking alcohol. The raid was at midnight, which is when customers leaving Billy Bob’s after a concert often fill the Neon Moon, looking for more music and dancing. Potential customers saw the police activity and film crew and moved on, ruining Rhea’s biggest night of the week. Police found no minors drinking that night and wrote no citations at Neon Moon, and then they moved on to other clubs.

Grady justifies his actions by saying that the Neon Moon serves alcohol to minors, Rhea said. However, the Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission shows a relatively clean bill of health, with only two TABC violations in seven years. “I don’t consider [Rhea] a bad operator,” said TABC Lt. Karen Smith. “If he’s only had two administrative cases since he [opened] in 1997, that is not a serious problem. It’s nothing we’re concerned about as far as looking to protest his application or revoke his permit or anything like that. He’s always seemed very willing to cooperate with us.”

TABC spends a lot of time in the Stockyards, and there have been problems with bars serving minors in the past, including at the Longhorn years ago. “That was a problem but ... it was not under Darren; it was different ownership,” Smith said. She said TABC has not received complaints from police about Neon Moon.

So, Rhea wonders, what’s the police’s problem? “If my regulatory agency doesn’t have a problem with my bar, why does Grady?” he said.

Manning said he wasn’t aware of any conflicts between Rhea and Grady prior to Grady’s assignment at the Stockyards. Grady was working in the vice squad but wasn’t assigned specifically to the Stockyards area when the Longhorn incident happened. Grady refused to discuss specifics about Rhea because of pending litigation. Rhea’s lawsuit seeks unspecified monetary damages for closing down his bar early, along with attorney’s fees.

“There has been no one singled out for any special attention or action,” Grady said. “I am the focal point for some of this because I am the commander of the area. I believe I’ve treated everybody fairly. I don’t always expect people to agree with me, but if you look at the big picture, you’re going to see that nobody has been singled out.”

Grady appears to have been consistent in his parking tickets, spreading them out from one end of the Stockyards to the other. Sunday afternoons in the Stockyards once meant row after row of expensive motorcycles lining the wide sidewalks near the various Riscky’s restaurants on East Exchange Avenue near the railroad tracks. Bikers sat on the patios, drank beer, listened to outdoor bands, and admired their chrome and rubber machines glistening in the sun. Tourists also seemed to enjoy strolling the sidewalks and looking at the cycles, which could number up to 200 on a good day. Then, two years ago, police began telling the cyclists to vacate the sidewalks and curbs, and to park their bikes in parking lots around the corner, which were out of their view. The bikers balked.

“The Harley deal is, everybody wants to stand around and look at their bikes and talk about their bikes,” said local businessman Mike Wilie, who has lived in Fort Worth since 1976 and driven a motorcycle for 35 years. “You’re not supposed to park on the [Stockyards] sidewalk but, you know, it’s a pretty wide sidewalk, and it’s not restricting the flow of people.”

A few tourists would occasionally express apprehension about the bikes or their loud engines, but overwhelmingly the reaction was positive, he said. “I enjoyed watching the tourists as much as the tourists enjoyed watching the bikers,” he said. “The kids marveled at the bikes. There was vitality to it, diversity. Cowtown ain’t just for rednecks anymore.”

Go to East Exchange on Sunday these days and you don’t see many bikers. They left and took their money with them. Inside Riscky’s Catch is a wall with framed photos. One picture shows a long line of motorcycles on the sidewalk; in the other, the sidewalk is empty except for one motorcycle — a police motorcycle. “It’s okay for the police to park there, but nobody else can,” an employee said recently, her bitterness evident.

Being proactive and writing tickets is his way of leading by example, Grady said. The same proactive approach is used regarding minors drinking alcohol, he said. “I would prefer to address it before it becomes a problem and not wait until there is a full-blown epidemic of underage drinking,” he said. “You do have to worry about underage drinking at every place that sells alcohol.”

Not everyone buys his reasoning, including the Rodeo Plaza’s manager Costanza. Neon Moon is one of his tenants, and he wonders if it is a coincidence that Grady is focusing on a bar owned by someone he has clashed with, a bar that plays alternative rock and hip-hop music in an area infatuated with the Old West. “Some individuals don’t want hip-hop music in the Stockyards,” he said. “I do believe that [Rhea] tries his best not to serve any minors. You know as well as I do that if a minor wants alcohol, they will get alcohol. There are ways to do it. People can get false IDs.”

He is unwilling to choose sides in the lawsuit between Rhea and Grady, preferring to let the justice system decide. But something’s got to give. While police are concerning themselves with parking tickets and minors in possession, Costanza has noticed an increasing amount of vandalism and burglaries after closing hours. “I have had more vandalism in the first six months of this year than I have in the previous 10 years combined,” he said, adding that more than a dozen burglaries have occurred recently at the Rodeo Plaza building. “As far as I’m concerned, there has been a huge increase in crime.”

He wonders why Grady and his officers are harassing customers, delivery drivers, motorcycle riders, and bar owners instead of focusing on burglars, vagrants, and vandals who strike after hours. “Maybe that’s the way to get promoted in the police department,” he said. “I would rather get promoted by solving real crimes. They’re spending all this time trying to find some kid drinking a beer. If the purpose of police departments was to stop 19-year-olds from drinking beer, we shouldn’t have a police department.”

Email this Article...

Email this Article...