|

|

‘I want to be the male Erykah Badu for Fort Worth.’

‘I want to be the male Erykah Badu for Fort Worth.’

|

‘I’ve been digging a tunnel ... and I think I’m starting to see some light at the end.’

‘I’ve been digging a tunnel ... and I think I’m starting to see some light at the end.’

|

‘Am I singing about my girlfriend or am I singing about God?’

‘Am I singing about my girlfriend or am I singing about God?’

|

‘I decided to ... just trust that I was moving in some kind of right direction.’

‘I decided to ... just trust that I was moving in some kind of right direction.’

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Above the Crowd

\r\nThe hottest new star on the neo-soul scene is a proud son of the Fort.

By JIMMY FOWLER

The voice is smooth as melted Häagen-Dazs, gentle, gospel-tinged. “My mind is gone, I’m lost in your world,” he croons. “By the end of the night, my money’s all gone. Your sexy body aims to trick me.”

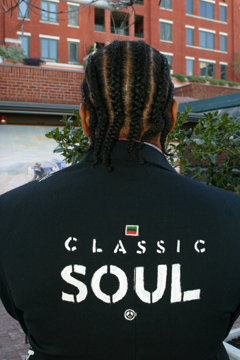

The artist who’s christened himself Nuwamba (pronounced noo-WOM-bay) is standing amid the accoutrements of a minimal home-recording studio, equipment scattered across the wood floor of his new house in Frisco. In baggy jeans and brown cap, he sings, forefinger stabbing the air to keep the beat.

Nuwamba — still known as Demetress “Dede” Cook to his numerous friends and family back in Fort Worth — has been pacing around, trying to explain that there’s a story hidden in most of the tunes he writes, but that listeners have to catch the clues to decode them. To demonstrate, he’s launched into an impromptu a capella rendition of “Tease,” a plaintive, seductive groove from his recently released debut album Above the Water. The song would seem to be a straightforward appreciation of a woman’s ability to work her man into a horndog tizzy with the slightest shimmy of her body. The unexpected performance is a knockout, utterly devoid of American Idol-style histrionics.

He pauses for a moment to drop a bit of food into a tiny fishbowl where a black Betta — a Japanese fighting fish — swirls and curves in the water, and then continues the explanation.

“It’s about strip clubs, man, and what a big waste of money they are,” he says. “A stripper’s job is to act like she wants you, like she’s going to go home with you, even when you both know she’s not going to. And you’re the chump left with the empty wallet.”

Still, there’s nary a “bitch” or “ho” reference in “Tease” or anywhere else on his hip-hop-tinged but sensationally old-school Above the Water — the narrator of the song makes it clear that he’s the one who deluded himself into dropping all that cash. And Nuwamba has just made it clear, with a few minutes of off-the-cuff warbling, that he can raise serious gooseflesh.

The Fort Worth music scene, and North Texas in general, may not yet know who their native son is, but let’s hope they won’t be the last to find out. The 31-year-old singer-producer-instrumentalist spends much of his time in Los Angeles and New York, where interconnected neo-soul scenes are grooming for superstardom this handsome fellow with the earthy, insinuating voice and penchant for love songs with mystical-spiritual underpinnings. The Hollywood-based black indie label Chocolate Soul, along with Nuwamba’s own Born Soulful Entertainment (he calls the production company “an urban alternative music outlet”), have co-released Above the Water, which is getting regular airplay on Sirius and XM satellite radio as well as influential FM stations in Philadelphia, San Francisco, Atlanta, and Washington, D.C. And c.d. sales are beginning to move in countries like Japan, Germany, and Australia.

Nuwamba makes no bones about being ambitious, but his goals are both more sophisticated and more clearly focused than your typical quest for money and fame. He hopes to replace the street-thug shtick now in favor among male neo-soul artists with charm, sweetness, and an Al Green-style “Am I singing about my girlfriend or am I singing about God?” vibe. He wants to oversee the development and promotion of other young black musicians from Texas. And he’s determined to become both an anchor and uplifter for the south Fort Worth neighborhood where he grew up — not bad, considering that in 1996 he did a seven-month stint in the county jail for what he still insists were 100-percent bogus charges.

“I want to be the male Erykah Badu for Fort Worth,” he declares, referring to the Grammy-winning singer who’s maintained a home base in her native Dallas and continues to foster artistic development in that city’s African-American community. The confidence, the preternatural centeredness in Nuwamba’s voice as he checks off his plans makes it all sound not only do-able but somehow destined.

Nuwamba is much happier talking about his music than his personal life. That’s partly because he wants to establish a certain public mystique and partly because he’s determined to build a zone of privacy now against the intrusions that may come if the fame train continues to pick up speed. He must be persuaded to relate some of the experiences he had growing up in and around what he calls “middle-class black Fort Worth.” He still keeps in close contact with his parents, his five brothers and two sisters, his cousins, and many friends there, despite the obligations of a burgeoning musical career that keeps him on the road.

What information he is willing to part with sketches a picture of a childhood framed by the powerful influence of his mom, the musical talents of his dad, and a love of arts of all kinds, from painting to poetry to eventually singing and writing songs. And, in the background, hints of temptations not so positive.

He spent many of his early years on Fort Worth’s south and east sides. His father worked as a church organist. His mother, whom he calls “the most righteous person I know,” constantly played Isaac Hayes, Marvin Gaye, and especially Anita Baker as she cleaned the house. An early and formative memory for Demetress was standing onstage in Sycamore Park with his father’s mess-around band as they churned out a ’70s-style funk groove. But for a long time, music was a background, a fact of life more than a calling.

“I was more artistic than musical,” Nuwamba said. “I drew, I painted, I did computer graphics. And I started reading early — the Bible, Langston Hughes’ poetry, and a lot of what they call ‘motivational books.’ You know, the ‘how to find yourself’ stuff.”

Eddie Cook, a high school football coach in Como, is Nuwamba’s big brother and self-appointed “motivator.” As they grew up together, Eddie noticed that his little brother had inherited obvious traits from their father (who plays multiple instruments and learns music by ear) and their mother (who has “a strong will and the desire to get things done right”). But Dede differed from his siblings in some ways.

“He played sports, but mostly while the rest [of the brothers] were out playing football, he’d be inside painting,” Eddie said. “He was also into looking super-cool all the time. Most of us would just throw our clothes in the dryer; Dede had to iron and starch it up.”

While singing in the choir at Southwest High School, Demetress also began, like a lot of black male teen-agers of the ’80s, to write and perform rap songs with his friends and Eddie (while sporting an atrocious Afro, he confesses). Although he didn’t stick with hip-hop long, he credits that dabbling with making him a better songwriter: “Rhyming helps your vocabulary, and it helps you stick with a song structure.”

One day it just sort of struck him that something he’d always done well, that people had frequently complimented him on, was the one thing he’d always taken for granted — singing. Toward the end of high school, he read Divided Soul, David Ritz’ intensely psychological biography of Marvin Gaye, and in some inexplicable way identified with it.

“The spirituality and the sexiness, the idea that you could be soulful and charming and masculine at the same time — it just really changed my life,” Nuwamba said. “I think everybody who wants to sing should read it.”

He’d also begun building a spiritual identity. Books about Christian, Muslim, and Buddhist philosophies — especially those that made comparisons among those beliefs — drew him in. When his parents converted to Islam, he visited the mosque a few times with them, and that experience went into the mix as well.

Shortly after absorbing the lessons of Divided Soul, Demetress and a few of his friends decided to form a “black boy band”-style group fashioned after New Edition and Jodici. They tossed off original tunes for kicks and taped their harmonies on somebody’s old four-track recorder at home. As he became more confident as a songwriter and a lyricist, Nuwamba felt all the creative impulses he’d channeled in so many scattershot directions beginning to coalesce into an expression that felt natural and, in some cosmic sense, pre-ordained. He fell in with a crowd that loved to read and discuss African culture and its roots in America. The name “Nuwamba” — which means “November” in a Swahili dialect — occurred to him in a dream, and he adopted it as a professional name for a profession he was just beginning to prepare himself for. He didn’t know that he would soon be compelled to “pass through the fire,” as he calls it, before he could resume his artistic journey.

Nuwamba knew many guys in school and after graduation who succumbed to the temptations of the fast and flashy lifestyle provided by selling crack and meth. He’d seen friends and acquaintances become addicted and die from overdoses or, more violently, in shootings.

But Nuwamba and his brother Eddie both recall how their mother, a deeply moral person who’s sensitive to the traps that young black men in the city too often fall into, worked tirelessly to convince all her sons to stick with a straight path of responsible behavior. Nuwamba remembers one time as a high school sophomore when he attended a party she’d explicitly forbidden him to go to — she knew there would be gang elements present — and, sure enough, he got caught in the crossfire. Literally. He’ll happily show anyone the slight scar near his temple where a bullet grazed him, a silent testimony to the price of ignoring her warnings.

That wasn’t his only near-miss. In the years just after he graduated from high school, he got arrested twice, once for a bar fight and once for threatening to kick an apartment manager’s ass. He pleaded guilty to one and no contest to the other and spent a few days in jail both times. “I can’t really explain where my head was at” during those years, he said with a pained chuckle.

Still, he generally avoided serious trouble. So it was something of a shock to the Cooks when in 1996 their Dede, then 22, found himself in the Tarrant County jail charged with aggravated assault with a deadly weapon on a police officer.

Nuwamba said the officer in question, a white beat cop, was notorious for harassing young male residents of south Fort Worth’s African-American community — someone, he admitted, he’d “mouthed off to” on several occasions.

The officer claimed Nuwamba had pulled up beside him in a car, drawn a handgun, taunted him, and then sped off. There was just one problem, according to the singer — he was in New York City on the night the incident allegedly occurred, and he had the airline ticket stubs and multiple eyewitnesses to prove it. He’d flown up with his little brother and a few friends to hang out with some rappers who had Fort Worth ties.

Nuwamba returned home to discover there was a warrant out for his arrest. He turned himself in, but, he claims, getting people in the sheriff’s department or the district attorney’s office to listen to him proved difficult. His bond was set high enough that it would cost thousands of dollars to get him out. His family struggled to find the cash as well as a defense lawyer who would agree to take on what the Cooks thought was an outrageous and easily provable case.

He wound up languishing for seven months in the county jail. He was devastated. All of his spiritual study was put to a practical, if grueling, test.

“I prayed a whole lot,” he recalled. “And I played a lot of basketball. I even sang a little bit for some of the guys. I said to them, ‘Hey, man, I’m innocent, and when I get out of here, I’m gonna be a musician.’ They were like, ‘Yeah, bro, whatever.’”

In his cell, Nuwamba wrote an early draft of “Above the Water,” the song that would later become the title track of his debut c.d. At the time, he said, “I was fighting to do just what the song says — ‘Tryin’ to keep my head above the water.’ My self-esteem was completely shot.” In the version that was ultimately released, the tune is a mid-tempo, organ-laced contemplation about the legal, economic, and family problems that bedevil black men.

The district attorney’s office ultimately dropped the aggravated assault charge, and the whole incident was expunged from his record. Purging the residual emotional effects was not so easy: A year of alternating depression and rage ensued, the singer said, before he was finally able to get back on track. The frustration pushed him toward deceptively easy ways of moving his life forward after he’d been pulled out of the dark hole.

“I can’t lie — sometimes [the so-called easy life] looked tempting, but I decided not to go that way,” he said. “My mother says, ‘When you recognize evil, how can you not flee from it?’ I decided to go without electricity or groceries a few times, to let the bill collectors bug me when I missed a payment, and just trust that I was moving in some kind of right direction.”

By 1999, the singer was opening for national acts like Frank McComb and 95 South at the Argon Ballroom, The Midpoint, and other black clubs around town. Through those gigs and various part-time jobs, Nuwamba piled up enough capital to gradually begin recording professional demos of some of the songs that would later be included on Above the Water. He supplied keyboard, guitar, and digital drum sequencing for the tunes. Eddie and a few other confidantes were the first to hear them. “Big brother motivator” would bluntly send him back to tweak the work when it came up weak.

“Man, I don’t know anything about the music business,” Eddie said with a laugh, “but I know what sounds good. And I also saw that Dede was pushing too hard to make it big too fast, without doing the work he needed to do” on the songs.

A chance encounter at a car wash connected Nuwamba with another aspiring neo-soul artist named Chris Jasobe, who has since become one of his best friends. Jasobe and his wife relocated from New York City to Fort Worth in 2001. He describes himself as a jazz-influenced singer-songwriter shaped by ’70s masters like Stevie Wonder and Donny Hathaway, although he won’t claim he and Nuwamba are on parallel paths musically. One important element distinguishes them: motivation.

“There are artists who’re just as talented as Nuwamba, maybe more talented,” Jasobe said. “But most of them don’t have the relentless, goal-oriented ambition that he possesses. You could even use the word ‘obsessed.’ I have to say, sometimes I envy that. He’s decided to live the risky life of an artist, outside of the corporate safety net.”

Jasobe accompanied his friend to the studio and pitched in with backup vocals and some songwriting and arranging ideas, but he said that Nuwamba always had “the whole picture” in his head, including melodies, harmonies, production, mixing, and why a flugelhorn would work better than a saxophone in a particular spot.

After Nuwamba got the songs sounding exactly the way he wanted them, he passed c.d.’s around to friends and friends of friends who knew DJs, club owners, record producers, and anyone who might declare out loud, “Hey, this Nuwamba guy is really good.” Fortunately, someone in a position to further his career happened to be standing nearby.

The coincidence makes sense to Nuwamba. He’s a big believer in synchronicity and a mystical give-and-take he calls “The Truth,” which basically amounts to: If you live your life creatively, sincerely, and righteously, the right people and events will fall into your path.

So far, so good.

In 2001, a former employee of the then-Atlanta-based black indie label Chocolate Soul moved to Fort Worth and met Nuwamba at a music store where the young singer worked. The manager allowed him to spin his own demos on the store’s c.d. player. That’s how William Griggs, owner of Chocolate Soul Entertainment (which has since set up shop in Hollywood), got a copy of the song “Take Me Away.” The former employee passed the demo along to Griggs, who was impressed by what he calls its sincerity, its musical inventiveness, and an elusive quality in the singer’s voice that conveyed maturity beyond his years. The label chief put Nuwamba’s tune on one of his national Chocolate Soul Compilations of mostly unsigned but promising talents.

Nuwamba trumpeted himself as a “neo-soul” musician proudly during their first meetings, although Griggs says the term has little practical meaning except as a marketing label first employed in the ’90s for artists like Erykah Badu, D’Angelo, and Me’Shell Ndegeocello.

“Neo-soul has elements of classic soul, hip-hop, and jazz,” Griggs explained. “The audiences for it are generally college-educated black professionals. A lot of people consider it a high-brow form of pop music.” At its worst, he said, “it can be standoffish, elitist, a little cold.”

Their professional association grew as Griggs recognized a quality in Nuwamba that he describes as a rarity among artists: a strong business sense. In describing his hopes for his own Born Soulful Entertainment company, the young Fort Worth musician displayed a grasp of what a startup production/promotion/artist development enterprise could achieve and the small, practical steps that could be taken toward achieving it.

Inseparable from this business plan was a sophisticated sense of his forerunners in classic and neo-soul, bebop and acid jazz, and the blues: He could name all the influences and where they fit into the music, his own and other people’s. Griggs soon realized that Nuwamba possessed a populist kind of appeal, a warmth and universal emotionalism that, he said, “would appeal to single black female professionals who buy $6 lattes at Starbucks and the little gangsta wannabes who run around in white tees and fix cars for a living.”

“He has something that a lot of today’s music lacks: authenticity,” Griggs said. “He’s more interested in telling a story with his songs than a lot of songwriters. Country-and-western has retained that connection, and I’m convinced that’s why it sells so well.”

Within two years, Griggs sent Nuwamba into Dallas’ Luminous Studios to complete the collection of songs that became his debut c.d., Above the Water. It’s the first full-length album by a single artist that Chocolate Soul has so far released and distributed. The release was done in association with the musician’s Born Soulful imprimatur.

Chris Bell, an accomplished engineer who’s worked with Polyphonic Spree, Erykah Badu, and N’Dambi — an artist Badu helped discover — mixed the c.d. at Luminous. He said Nuwamba came into the studio with a very clear concept for what the album should sound like, and while he didn’t hang over Bell’s shoulder and try to second-guess his choices, he wasn’t shy about stepping in and clarifying his wishes.

“I think he was disappointed [with a lot of other engineers] before he came to me,” Bell said. “But they told him that the neo-soul stuff is right up my alley. He’s different [from other artists of the genre] in that he likes to layer his vocals the way old-school soul artists did. Neo-soul singers often use a single vocal line. I did a lot of vocal stacking for the album. The way he uses harmonies is also terrific.”

The national reviews for the album in magazines like Right On!, Upscale, and Urban Network have been raves. Critics have gushed about Nuwamba’s “heartfelt, Southern-spiced tenor” and called the c.d. “thematically and musically awesome” and “among the finest of the year.” Best of all, Nuwamba is seeing his name appear in those glossy pages alongside established artists in the urban/R&B/hip-hop firmament. The juxtaposition seems to say: “Isn’t this guy a big star already?”

And so for the last two years, Nuwamba has been speeding toward a future that family and associates hope includes big money, international acclaim, and other karmic rewards. The income from radio play, club dates, c.d. sales, and house parties — most of which occur outside the Fort in places like L.A., New York, Atlanta, and Philadelphia — as well as the odd survival job, has enabled him to buy his home in Frisco, which admittedly is a long drive from family and friends in Fort Worth, but also a place where an emerging national artist can get a lot more house for the money.

For the young man and his music, the outlook for the next 12 months is busy, thrilling, and uncertain. He recently returned to New York City to tape a featured interview and brief a capella performance for the Japanese radio show World MusiX Live From New York, which is syndicated on the country’s largest commercial network and has an estimated listenership of 10 million. His c.d. is about to be re-released as a collection of new remixes for the DJ/club market. Nuwamba and Griggs are preparing a short, five- or six-city tour of the Midwest to follow up earlier gigs in Los Angeles, Baltimore, and Houston. After that, he plans to go overseas and hit cities in Japan, Australia, and Germany.

In the meantime, a couple of different major labels are eyeing Nuwamba, though no contracts have been signed. Griggs would be thrilled to see the artist get snapped up by some music-industry powerhouse. Under the current agreement between Chocolate Soul and Born Soulful, Griggs would get a co-production credit and financial cut of Nuwamba’s first major label release and, possibly, future projects.

All this means Nuwamba’s frequent- flier miles will shoot through the roof in 2006. He is fiercely proud of his family and his hometown in Texas and has so far refused to listen to pleas that he move from his base. “I don’t have any problems with kicking back on the plane,” is how he describes his peripatetic schedule.

Griggs, who admits he’s one of the people who’s tried to persuade the singer to relocate to one of the coasts, believes there could be a cost for such loyalty.

“I see the beauty” in trying to maintain a sense of your roots, he said. “But the reality is, you’re always going to be one step behind [in the music business] if you’re not living in New York or Los Angeles. If a major label decides they want to beef up their roster of soul artists, he’ll be that much slower to the punch.”

Chris Jasobe has since returned to New York City and encouraged Nuwamba to follow, so he can spend less time in the clouds and more time pounding the pavement, promoting himself and his c.d. Since he has made little headway in changing the Fort Worth artist’s mind, Jasobe calls himself “the unofficial East Coast rep for Born Soulful,” devoting much of his spare time to making phone calls, mailing out press releases, and pressing the flesh with club owners and radio station programmers.

“Nuwamba and I are friends first,” and professional associates second, he said. “He knows my apartment is always available when he needs to head up here and do some business. And whenever he comes and stays, we hit the grind full-time.”

Of course, Nuwamba will still have to depend on New York or L.A. to hit the big time regardless of where he chooses to live, and he knows it. Erykah Badu, after all, didn’t break out from Dallas: The clubs and radio stations of Brooklyn were the first to gild her rising international star. But she has kept her heart — and, whenever she can, her feet — firmly planted in her hometown, and that’s the example Nuwamba cites almost obsessively as the one he’s determined to follow. Under his Born Soulful Entertainment banner, he has begun working with his younger brother, an aspiring rapper, as well as an established Fort Worth hip-hop artist named Jurah. He’s hoping to provide a jumpstart for their careers — as soon as his own goes into overdrive.

“I’ve been digging a tunnel [with music], and I think I’m starting to see some light at the end,” he said with a broad, almost feverish grin. “And I want to bring other people and their ideas through the tunnel with me. That’s how you uplift a neighborhood, a community, a city. That’s how you help bring the world to Fort Worth.”

Email this Article...

Email this Article...