|

Major labels ‘just have no time for artistic development.’

|

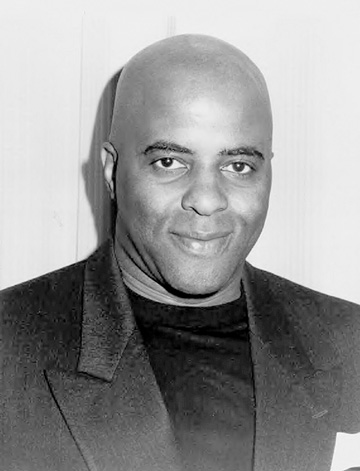

Veteran music insider Terry McGill says that artists must take all available avenues to succeed.

Veteran music insider Terry McGill says that artists must take all available avenues to succeed.

|

|

‘Just because it’s quick and cheap doesn’t mean it’s good.’

|

Local independent alt-rocker Dustin Rall of JustCause knows that digital jukeboxes aren’t going to make or break his band’s career.

Local independent alt-rocker Dustin Rall of JustCause knows that digital jukeboxes aren’t going to make or break his band’s career.

|

| \r\nDigital jukeboxes allow you to download music onto your computer for about a dollar per song, then transfer your music to a portable digital player. Here are some of the more popular sites.\r\n\r\nwww.itunes.com\r\nwww.musicmatch.com\r\nwww.napster.com\r\nwww.connect.com\r\nwww.rhapsody.com\r\n\r\nAll you need is a credit card to get started.\r\n\r\nMillions of songs are available online but not every song. Expect not to find certain popular tunes. |

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Peas in iPod

Digital music may set us all free — \r\nor just change the color of the chains.

By ANTHONY MARIANI

Where’s a music fan to turn? Radio sucks, chain record stores suck, and major labels are only interested in stuffing pseudo-punks and bodacious babes down our throats.

The internet? For a lot of folks, yes. It’s been the saving grace for underground/independent (a.k.a. “undie”) rockers and rappers and their fans for years. Sure, it hurts major label artists whose music continues being downloaded illegally in mass quantities, but let’s not cry for Lars Ulrich or Bruce Springsteen because neither can buy his mistress another diamond ring. And I’m not bawling for their Madison Avenue bosses, either.

The best thing about the internet, though, isn’t audible — unless the sound of a crumbling record industry counts. Big radio is hemorrhaging listeners. The Big Five record labels are shedding employees like dope dealers tossing their stash before The Man arrives. Chain record retailers are closing. The evil despot who unceremoniously foisted boy bands and teen queens on us is on his way out. A new, digital cyberworld is on its way in.

Pardon the artists if they’re a little leery.

It seems that nearly everyone you see is wearing one of those little digital music player earpieces. You know who makes those? Not the mom-and-pop electronics retailer down the street, that’s for sure. Some of the scavengers feeding off the carcass of the music industry are the size of corporate saber-tooth tigers. In the words of The Who: “Meet the new boss / Same as the old boss.”

A lot of musicians, intimately familiar with the pain that the industry can inflict, are refusing to hang their careers on a single communications device, no matter how sexy, because of its corporate lineage. Some wily musical entrepreneurs are even turning their backs on cyberspace to build a strong traditional underground economy out of the detritus of the crumbling industry. They’re summoning the spirits of yesterday’s musical pioneers: The Seattle slackers who resurrected punk for the masses. The South Bronx teen-agers who without instruments made music out of extended-dance breakbeats, microphones, and nursery rhymes. The Delta blues guitarists who rocked their songs to the beats of locomotives.

Even a certain Cleveland DJ who played songs in return for cold hard cash.

I Want My iPod

The newest twist in the music world is the legal on-line digital jukebox. Up until about a year ago, the only way to download music was illegally, through free file-sharing services like Napster or Kazaa. Then Apple Computer introduced iTunes. With more than a million songs, from the Big Five major labels and 600 independents, iTunes — not the first legal digital jukebox but the best — accounts for more than 70 percent of all legal music downloads. (The site recently surpassed 100 million downloads, at 99 cents per song, around $10 per album.) Digital jukebox sales overall, according to data provider Jupiter Media, are expected to reach $270 million this year and by 2009 could rise to $1.7 billion. Apple is at the forefront of a new era.

At around the same time iTunes rolled out, the iPod hit shelves. A digital music player no bigger than half a deck of cards yet capable of holding up to 10,000 digitally formatted songs, the gadget is endowed with as much hipster cachet as a cell phone had in 1999. More than 3 million iPods have been sold, at $249-$399 per unit. You remember inviting friends into your house to show off your record collection? Well, now you can carry your record collection around with you, even force it on other people.

I recall one recent night at The Cellar, the notorious West Berry Street hangout renowned for its three-dimensional jukebox. Some folks have criticized the juke for its lack of local c.d.’s, but since the club caters to college students — most of whom are more interested in getting dates than being true to local troubadours — Cellar staffers don’t care. The jukebox, never mind its flaws, is a decent reflection of a young person’s life. Wanna party? Guns N’ Roses. Wanna make-out? Al Green. Wanna contemplate the great hereafter or your beer or the great hereafter in your beer? Wilco. The juke’s probably the best in town, which is why the sound of Led Zeppelin’s “Battle of Evermore” ringing through the place that night wasn’t a shocker.

But the c.d. on which the legendary rock band’s most Lord of the Rings-ish track appears wasn’t in the jukebox. It was in the bartender’s iPod, running through the house speakers.

Apple, the leader in the legal digital music downloading field, is not a music company, something that artists and music fans should keep in mind. Its primary function is to create, distribute, and sell software and hardware. The company loses money on every download. Music is not a priority. Selling iPods is. “On-line music,” according to a recent editorial in Wired, “seems to be more valuable not as a product itself but as a service in support of some other business model, selling coffee, hamburgers, or iPods.”

Apple got into the music business late. During restructuring in the late 1990s, Apple co-founder Steve Jobs realized the possibilities in the burgeoning digital music scene. The company introduced iTunes and iPods around the turn of the millennium. Compared to other digital jukeboxes and players on the market, which were cheaply made and designed, iTunes and iPods were gold, even though iPods were compatible only with Macs. Mac users — who constituted a mere 20 percent of the computer market but were steadfast in their brand allegiance — ate the gadget up, making it a hit. Apple soon released a digital interface for both Mac and Windows, increasing the fruity company’s market by more than 75 percent.

The timing was perfect for Apple. As the computer monolith was entering the digital music universe, the Recording Industry Association of America, the trade group that represents the interests of the Big Five record labels, was suing illegal downloaders, including 12-year-old girls. The RIAA essentially scared music lovers into Apple’s waiting arms.

Empty Wherehouse

The growth of iPod Nation has all kinds of fallout, but it’s hurting music retailers the most. Even though c.d. sales are up 7 percent compared to a year ago, c.d. sales overall have been slumping over the past four years. Niche record stores, like Tower Records and Wherehouse Music, are dying. Wherehouse has filed for bankruptcy, while Tower has posted a net loss every year since 1999, as owners pay off a $312 million loan for a late-1990s expansion. Blame illegal downloads and pressure from big discounters like Wal-Mart and BestBuy, which can sell music cheaper because it’s not the only material good they offer. Chain record stores that have tried e-tail operations have failed. The ones trying to put together digital jukeboxes — a consortium of brick-and-mortar retailers called Echo — are also floundering.

Major labels are partly to blame for record retailers’ imminent demise. Record companies buy space in retail stores, chiefly to promote certain bands. This makes retail dependent on label money. When illegal downloading came along, it paralyzed both the labels and record retailers. The labels, thanks to legal downloading, are recovering. Retail is still reeling. (Unlike record stores, iTunes doesn’t sell space in its “store” — its home page — to any advertiser, large or small, to keep the playing field level, according to the company line.) Legendary specialty stores, like Waterloo Records in Austin and Sound Exchange in Houston, should be OK. They cater to collectors, a loyal bunch cut from old, raggedy cloth. “Better record stores are always going to be around,” said Erv Karwelis of Dallas-based Idol Records, whose entire catalog is available on iTunes. “Chain retailers might not be so lucky. ... A lot of people prefer the digital format.”

Music fans have always harbored a certain amount of resentment over the high costs of recorded music. Then two years ago, their suspicions were confirmed, when two states, joined by 39 others, sued the Big Five and three of the country’s largest retailers for price-fixing. The states won $75.7 million in c.d.’s to be distributed to nonprofit groups and $67.4 million in cash.

So, many people aren’t mourning the death of brick-and-mortar record stores. Buying online is convenient, and the music is affordable — if you have a computer, money for an iPod, and the desire to learn how to use it. The range of music available would take Big Radio’s breath away. Maybe even its lifeblood.

Radio, What’s New?

Big Radio had everyone cornered in every market. Then the tekkies dug a hole, and an entire world of musicians and fans escaped. Digital recording allowed undies to make their own music, digital downloading allowed their fans to get it, and now internet and satellite radio are setting up as major competition.

Two major companies, Sirius and XM Satellite Radio, are battling for supremacy in the satellite radio field. Sirius claims it has 500,000 subscribers, and XM says it has 2 million. These numbers don’t compare to those of traditional radio (some major market stations attract 2 million listeners weekly), but they’re still scary. Further haunting traditional broadcasters is the fact that the Federal Communications Commission recently ruled that satellite radio stations are not limited to national broadcasting. They can also tailor broadcasts to certain regions, offering local news, weather, and traffic, intruding on traditional radio’s turf.

Internet radio is also growing. More than 38 million Americans, according to data provider Arbitron, listen to internet radio in aggregate, or about 19 million weekly, up from 7 million four years ago.

The monopolies are reacting. Clear Channel Communications, the radio behemoth that owns nearly a half-dozen stations in almost all the major media markets, announced last month that on-air commercials would be reduced in frequency, to better compete with the internet and satellite radio. The company, however, said nothing about expanding its playlists. “Radio sucks,” said Mary G, manager of local rapper D’Mac. Big Radio may be the country’s one non-polarizing issue — everybody hates it.

The radio monoliths may not “get” good music, but they understand money and competition. Clear Channel now owns 30 percent of Sirius — yet another reason that musicians are wary of proclaiming “freedom.”

Big Radio still has a buddy in the major labels. Only they can afford to buy Big Radio ad spots — and therefore are the only ones whose music is played. “For the most part, commercial radio is off-limits to me,” said Idol’s Karwelis. “It’s still a money game. The majors still control it.”

But major labels are suffering too. They have reduced their staffs and no longer concentrate on developing artists but on churning out, marketing, and promoting a succession of flashes-in-the-pan. Major labels “just have no time for artistic development,” said Karwelis. They look for attractive young people whose talent may be suspect but whose sex appeal is off the charts and whose dirty laundry could fetch millions at auction.

What’s unusual is that this monster is one that downloaders created and continue feeding. Illegal downloading shot up by 35 percent in 2003; more than 2.6 billion files are illegally downloaded every month. The more money stolen from major labels, the more major labels will hedge their artistic bets and roll out more Blink-182 clones, something safe and guaranteed to sell.

I’m On The Radio Radio Radio

The purpose of being an underground or independent artist is to express yourself in your own unique way. You’re encouraged to “keep it real.” Despite the mindless programming of giants like Clear Channel, commercial radio has never been more popular among certain listener groups, especially the people who invented “keepin’ it real” — urban music fans. As general radio listenership across the country continues to shrivel up, according to Arbitron, urban radio (hip-hop/R&B) remains strong. It bests nearly every major market in the ratings every quarter. In Fort Worth-Dallas, the king, Radio One-owned 97.9-FM/KBFB The Beat, and its prince, 104.5-FM/KKDA K-104, both make regular appearances in top slots.

A recent study indicates that of all genres of commercial radio, urban radio plays the most regional artists. One explanation: Club payola or “playola.” It’s common for independent rappers or R&B artists or their managers to slip a club DJ $50 to play one of their songs — which is perfectly legal. If the tune is a dance-floor hit, it will eventually make its way onto local hip-hop radio. “But if the song’s mediocre or below-average, [playola] won’t make it a hit,” said veteran music industry insider Terry McGill, owner of Major Money Entertainment, a Dallas-based music consulting company. “If it’s good, playola can make it a hit.”

Another explanation: Good ol’ fashioned traditional payola. “People are going to do what they have to do to get their music played,” said McGill. “Payola is out there.” (It’s not endemic to urban radio. Pay-for-play has taken on insidious shapes across the rock radioscape. Avril Lavigne’s first recent single, “Don’t Tell Me,” had for weeks been hovering outside Billboard magazine’s weekly list of the top 10 most-played tracks, which radio programmers study to decide which songs to squeeze into regular rotation. An independent record promoter, hired by Lavigne’s label, Arista Records, then paid a country radio station in Nashville to play the song — as an advertisement, called a “spot buy,” like an infomercial — three times an hour, every hour, on May 23, 2004, between 6 a.m. and midnight. Within weeks, the song charted on the Billboard Top 40 in the top 10.)

A final explanation for regionalism in urban radio: Pluck and luck. “You need to meet people, like we do,” said manager Mary G whose client D’Mac is this close to breaking into one of the big urban radio stations’ irregular rotations. “Houston, Amarillo, San Antonio, you need to be out there, with your music,” she said.

Copies of D’Mac’s most recent c.d. include the instruction, “BURN THIS CD & PASS IT AROUND.” Said D’Mac: “Just because your song is on iTunes or radio does not mean people are buying it. You got to work hard.”

There’s another reason that urban music performers rely less on the internet than many of their counterparts in other genres: Poor people, who make up the majority of urban music’s fan base, are a whole lot less likely to buy iPods and top-notch computers. Market research shows that most iPodders are middle-class.

“Minority artists are always the last to catch on to new technology,” said McGill. “[Digital music], no one in hip-hop is really feeling it now. It’ll get there someday, though.”

Headkrack, local rapper and host of “Da Show” on The Beat, agreed. “The suburbs are hot on iPod,” he said. “But it has not caught up to hip-hop yet.”

Both undie rappers and rockers could miss the digital boat. “It does worry me,” said Headkrack. “In music, once it goes corporate, the small guy always gets cut out.” Undie artists and music lovers, he said, have a hard enough time reaching each other. The corporatization of the internet may only worsen things. “There are less and less ways for indie artists to be heard.”

Multi-platinum artist Peter Gabriel is similarly fretful. He told CNN: “I think it’s very important for artists to get involved in the distribution. A new world is being created — one is dying — and if artists don’t get involved, they’re going to get screwed, like they usually do.”

Some undie artists accept the digital jukebox as an important vehicle for getting their music into as many hands as possible. “It’s cool,” said Tahiti, one of the few local undie rappers to take a proactive approach to digital music. “I think it’s another opportunity for artists to get out there.”

Dustin Rall, frontman for local undie alt-rockers JustCause, is one of the hardest working musicians in town. He goes to nearly every big local-act show and is always passing out flyers or copies of his band’s c.d. He’s been trying to get JustCause on a popular digital jukebox but hasn’t had any success. Most digital jukes, including iTunes, have small, overworked staffs and rarely respond to unsolicited correspondence. Rall understands that while popular digital jukeboxes may help his career, they won’t make it. “We try to sell records and get exposure as many places as we can.”

A lot of undies, however, don’t really care or are steadfast in their solitude. They say the mainstream can have its fancy new world. “It’s like fast food,” said Kevin Aldridge, former frontman of defunct rockers Brasco and current frontman for the shoegazing sextet Chatterton. “Just because it’s quick and cheap doesn’t mean it’s good.”

‘Spress Yourself

Online jukeboxes aren’t the only way that digital technology is affecting music. The ease and relative low cost of digital recording technology is what has made independence from labels possible for a decade. Undie musicians — many of whose music is available on iPod — are by no means totally resistant to the digital age.

One popular internet option for undie bands not affiliated with any popular digital juke is the community portal. Two of these are www.myspace.com and www.musicgorilla.com. Rall said that after uploading his band’s music to myspace, he saw hits to his band’s web site triple. He also met some locals online, folks who ended up at a recent JustCause performance in town. “I’ve actually even sold some c.d.’s,” he said.

Another on-line option is the indie music haven www.cdbaby.com. Songs posted there are also available on iTunes (though not the other way around). Goodwin and the Snowdonnas are two local bands whose music appears on cdbaby. “It seems to be, far as I know, the largest on-line retailer, ahead of [Amazon.com] and eBay,” said the Snowdonnas’ guitarist and songwriter Otto, “and it’s all indie.” The retailer has sold more 1.2 million c.d.’s, earning artists a little more than $9 million.

While iTunes is not all-encompassing, it does offer a lot of great independent music, including the Idol Records catalog. One of the first 100 indie operations invited to the iTunes party, about a year ago, the label — home to Flickerstick, Sponge, and recent Warner Bros. signees The Fags — is a decade-old institution. Its brand of music is rough yet refined, retro yet forward-looking. Like the iPod itself, Idol is trés chic.

Idol’s Karwelis said he was contacted by Apple right before the iTunes launch. Idol music had been available for download on a site called eMusic for several years. The record company’s exclusive contract with the site expired around the time iTunes was making an offer. “It’s amazing,” said Karwelis. “We’re doing good sales.”

Karwelis had offers from several other digital jukeboxes. He went with iTunes first because, he said, the site had the most promise and biggest backing. The days of shipping c.d.’s across the globe, according to Karwelis, are over. “It’s only a matter of time,” he said, “before everything is on iTunes.”

As a result of the deal, Karwelis said he has more free time to concentrate on promoting and marketing his artists — ironically, a much tougher job now that digital technology has so thoroughly leveled the playing field and fragmented the music industry. Without promotion, for the average music consumer, the digital music world is just a long list of band names.

Find Waldo

The best way for a band to differentiate itself from millions of other, similar bands may be through radio. The average music lover, when capable of downloading nearly every song imaginable, is going to go with music that he’s heard on MTV, tv commercials, or radio. If presented with a choice between downloading a song by wildly popular national emo-rockers Death Cab For Cutie or locals Titan Moon, the average music lover is going to choose DCFC. They’re huge, especially on college radio. Some digital jukeboxes offer streaming audio, whose music cannot be downloaded, to let customers sample new music; iTunes doesn’t, but it provides links to internet radio stations as well as 30-second song snippets.

Whereas undie rappers and R&B artists have a handful of amenable radio outlets, local underground and independent rock acts have little. 102.1-FM/KDGE The Edge plays some local rock on certain shows, never during drive time.

One way for undie rockers to stand out is by becoming more visually prominent, which includes everything from making the scene in person to making videos. “Now it’s definitely visual,” said veteran insider McGill. “Include a music video with your c.d. There are other ways to get exposure.” Going on tv, putting up a web site, and taking out advertisements are some viable, legitimate ways for artists to increase their profiles, according to McGill. “You’ve got to find more outlets to get your name to the consumer.”

A lot of musicians are disheartened by the concept of the level playing field — the idea that if everyone’s a star, then nobody is. “It’s a popularity contest,” said local rap manager Mary G. “People don’t want to hear you unless they know you. They want you to blow up” — get recognized — “first, but how can you blow up when they don’t support you?”

As easy as it is to hate major labels, we secretly yearn for their good side — their long-lost ability to control what enters the marketplace. They brought us The Beatles, Dylan, Springsteen, and The Outkast, remember? Discerning major labels could come in handy now, considering that the national music press is toothless, more interested in king-making than taste-making. “Everybody and their mom has a c.d. out,” said McGill. “And they shouldn’t have a c.d. out. It’s like cars on the freeway. There’s a lot of traffic.”

One day recently I accidentally Googled “digital tracking” instead of “digital tracks.” What came up was a handful of sites for something called “tracking music.” I clicked on one, United Trackers, and was stopped in my, uh, tracks. Millions of songs everywhere, even though their authors were unknown to me. I dug a little deeper into the site and discovered a subculture of digital musicians called “trackers.” They create music on their computers, as you would a desktop publishing document. The tracker “plays” his QWERTY keyboard. Each key represents a certain note, each program a different instrument (from electric guitar to drums to saxophone). I clicked on a few songs. Not bad. Most belonged to some form of electronica, though there were country-western and death metal songs — a fact worth mentioning merely because the mental image of someone coaxing barre chords or lap-steel cries from his computer keyboard is downright surreal.

To make tracking music, you need to download specialized software (which is offered for free on some sites). But before you upload one of your songs, you better be sure you’ve mastered the form. Quality control in the tracking music world is done by the most critical gatekeepers you could imagine — the artists themselves. l

Email this Article...

Email this Article...