|

|

Kuban’s handpicked successor,

Kuban’s handpicked successor,

|

Kuban’s class makes weekly vis

Kuban’s class makes weekly vis

|

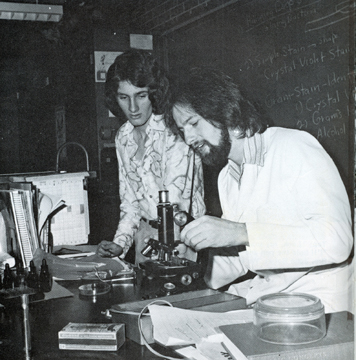

Kuban is shown teaching biolog

Kuban is shown teaching biolog

|

|

|

DeLane Kuban, a physical thera

DeLane Kuban, a physical thera

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Natural Man

Joe Kuban’s work and music have built an environmental legacy.

By JEFF PRINCE

A teenager was just itching to set fire to Tandy Hills Park. But maybe there were other ways to destroy the trees.

“You think they’d mind if I came in here with my chainsaw?” Austin Lanford asked award - winning environmentalist Joe Kuban. “I could cut a thousand of them. I have a big chainsaw.”

Kuban smiled — the idea wasn’t half bad, and it’s always nice to see a young pup eager to help.

The rolling hills of this Eastside nature preserve near I-30 and Oakland Boulevard are among the last remnants of undisturbed prairie grassland from Fort Worth’s earliest days. Before farms and townfolk took over, natural lightning-strike fires from time to time burned away saplings and kept grass abundant for free-roaming buffalo and deer. Nowadays, with homes and highway pushing in close around the park, controlled burns are dangerous and chainsaw work is labor-intensive. The trees are taking over. That’s why Kuban’s ecology class at Nolan Catholic High School has spotlighted the problems in a video that the students have entered in the Quantum Shift TV School Video Contest, hoping for the $50,000 top prize.

Doing big things isn’t unusual for these youngsters. This week, they’re heading to Big Bend National Park for five days of field research, studying plants and wildlife by day and camping under the stars at night. For 34 years, Kuban has been taking students on far-reaching ecological adventures while making history in environmental circles. His ecology studies program, established in 1974 at Nolan, was the country’s first at the high school level. Students make regular excursions to Big Bend, the Big Thicket, Port Aransas, and the Costa Rican rainforest. More than a few students have been inspired to pursue environmental careers, although that’s never been Kuban’s expectation.

“What I hope to do is make them more appreciative of nature,” he said. “You flat don’t know what we’re doing to nature if you don’t get out in it and understand its great beauty and great benefit to us. That’s the inherent value in the trips.”

Nature’s splendor has never been lost on Kuban, not as a boy growing up in rural Tarrant County, and certainly not now that he’s staring at a tricky future. Amylotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as ALS or Lou Gehrig’s disease, is stealing his hands, slurring his speech, crippling his legs. Eventually, he’ll lose the ability to talk or even swallow. Most people live three to five years with the disease. Doctors diagnosed Kuban more than a year ago.

If anyone is likely to accept and understand the circle of life, it’s a biologist and nature lover. Kuban is milking his remaining years. Despite leg braces, a motorized scooter, and flagging vigor, he’s still helping raise money for disease research. He’ll accompany students to Big Bend this week. And he’s recently finished his second album of songs dedicated to the huge West Texas national park and its topography. He barely managed to get his vocals recorded before ALS took his singing voice. This disease doesn’t pussyfoot around. Then again, neither does Kuban. He plans on going to Port Aransas for his class’ marine biology trip this spring, even if all he can do is “sit on the beach and feel the wind in my hair.”

The hair fell out long ago. His good humor is holding firm.

“Is this it? Is this Engelmann sage?” a student asked, bending over a plot of earth at Tandy Hills Park, poking his fingers in the dry grass and dirt. Kuban’s classes come to the nature preserve each week to document plant growth within four plots outlined by stakes and strings. Tandy Hills is one of the few places in Fort Worth where Engelmann sage grows wild. The flower is easy to spot in spring, when velvety lavender blooms open. In winter, though, it’s tough to pick out from all the other plants. The class designed plots at sites facing north, south, east, and west to determine how different exposures affect the wildflowers. It’s one of many research projects done under Kuban’s tutelage.

The video that his ecology class entered in this year’s Quantum Shift contest explores the challenges at Tandy Hills. Winners are judged on the quality of the video, as well as a grading system based on students watching and commenting on other entries. Currently, Nolan is ranked No. 27 out of 138 entries, with about two months remaining in the contest.

Kuban’s passion for ecology has earned him numerous professional honors, including the Jane Goodall Award in 1995 for his ecological research, and has made him a beloved if unconventional figure in the eyes of countless students.

“He’s the smartest person I know,” Jake Mullen, 18, said after class recently.

“He’ll bust out facts off the top of his head,” 17-year-old Joseph Alvarez said, marveling — and laughing — at some of the curious minutiae his teacher can spout.

I got a sample of that as I made small talk with Kuban at his Arlington home. When I commented on the plump red berries that hung from a holly bush in his front yard, Kuban’s eyes lit up. He described how, for birds, the berries are like tiny red cocktails at happy hour. Trace amounts of alcohol entice birds to gorge on the colorful fruit, and they catch little birdy buzzes, which sometimes make them crash into his windows. It’s all part of nature’s plan, he explained. Mama birds are anxious for babies to leave the nest. Drunken youngsters may not fly straight, but they can go really far — so far they never get back home.

Kuban, on the other hand, has avoided many of life’s “berries.” Drugs and booze were signposts of the counterculture revolution that was redrawing the social landscape when he came of age during the 1960s. But he kept his nose clean and mind clear. Even as lead singer with a rock group, pulling off passable renditions of Robert Plant and Jim Morrison, he kept drugs at arm’s length and focused on church and nature.

Nor did he fly far from the nest. He was born on the North Side in 1950, and his parents packed up the five kids and moved to Lake Worth in the early 1960s, where his love of nature was fostered.

“We always thought Joe was less practical than the rest of us,” Frank, the oldest sibling, said. “He’s always been interested in things that are natural — observing birds and lizards. He wasn’t weird, but he was different.”

Mama Kuban kept a one-acre garden and didn’t have to badger little Joe for help. Weeding and seeding were pleasures. “Just hanging with her and running my hands through the dirt helped make me who I am today,” he said, his voice choking.

Tears come easily these days. Heightened emotions are an ALS symptom, and it’s not unusual to catch Kuban crying over TV shows or even commercials. As symptoms go, crying jags are the least of his worries. ALS also attacks the nerves and progressively destroys muscle.

At the same time, the mind remains intact, making sufferers painfully aware of their own degeneration. Kuban’s body is wracked, but he keeps pushing, prompting a doctor to warn him, “You’re writing checks your body can’t cash.” Kuban’s wife, DeLane, is a physical therapist and helps keep him limber, but they both know what lies ahead.

By the time Kuban was a teenager, growing vegetables had taken a backseat to music. The Kuban kids were a musical bunch, and Joe and his two younger brothers sang in the Texas Boys Choir for years. Once his voice changed, Kuban left the choir and threw himself into Boy Scouts, earning just about every badge available. His parents, devout Catholics, enrolled their brood at Nolan. It was there that Kuban, an enthusiastic songwriter, drummer, and singer, started his first band, called Chain Reaction (his love of science was already showing). The Beatles had only recently captivated American youth, and a new musical era was dawning.

“For the next four or five years we played a lot of rock ’n’ roll,” he said.

The band would morph into Obie’s Potato Band, inspired by equipment manager Obie Obermark, who could pack a van so tightly that nary an amplifier nor mic stand would budge during transport. “I was the mascot, gopher, flunkie, whatever, and did what I could to help the band,” said Obermark, now a radio disk jockey at KNON and founder of Obie-Cue’s Texas Spice, which makes barbecue seasonings. “They figured out if they named the band after me they could stop paying me and I’d never quit.”

Back then, most band members were college students attracted to hard partying, including experimentation with psychedelics. Kuban, though, seldom ingested anything more potent than a cold beer. He stayed active in church, even writing the music for church mass and inviting his bandmates to come listen.

“That was during a rebellious period of time, and the thought of anybody being involved in church seemed goody two-shoes to me,” Obermark said. “We were all wild and crazy hippie punk student rockers. I thought he was kind of a weenie because he wasn’t interested [in rebellion]. As it turned out, he was the most adventurous of the entire bunch. He’s the one who goes out to Big Bend and camps out for weeks on end and does research and all this physically demanding robust outdoor stuff.”

Kuban majored in biology at UT-Arlington, earning his bachelor’s in 1972. He immediately began work on his master’s degree, and, at 23, was making decent money playing rock music at frat parties and local clubs. But what he really wanted was to become a scientist, scholar, environmentalist, and mentor. Offered the chance to teach at his high school alma mater in 1973, he jumped at it, even though it meant a substantial pay cut. His first year’s salary at Nolan was $4,000. “I was making more playing rock ’n’ roll, but I just couldn’t see that as my future,” he said.

School officials realized they’d nabbed a keeper and boosted his salary to $10,000 the next year.

Kuban queried students on areas of biology they preferred and found that most were interested in ecology. The next year, he implemented a weighty program designed for senior honors students. Wanting to start off with a bang, the young, long-haired, inventive teacher planned a field trip to Big Bend National Park — his first visit to the mountainous desert paradise and his first time to lead a class into the wilderness. He took 20 students and assorted chaperones and “fell in love with the place,” he said.

Kuban absorbed everything he could. Books on Big Bend filled his shelves. He concocted a plan that would allow him to spend more time in his newfound paradise — his master’s thesis would be on Big Bend’s five species of hummingbirds. He spent months studying the aggressive little boogers and documenting how they coexist. Big Bend became his second home.

“Of all the places I’ve been on Planet Earth, it means the most to me emotionally and spiritually,” he said. “It makes perfect sense why Jesus would hang out in the desert for 40 days and nights.”

Studying birds meant hunkering down in their terrain. There are few things more important to a Big Bend hummingbird than hovering over a century plant and tapping into its stem, which drips with a sweet liquid known as honey water. Mexicans refer to the century plant as the “cafeteria plant” because so many animals and insects rely on it for sustenance. That same honey water also attracts humans — the liquid is fermented to produce pulque and then distilled to make the powerful intoxicant mezcal. A cousin of the century plant, another member of the agave family, produces a different kind of intoxicating liquor — tequila.

Having researched the hummingbirds for his master’s thesis, Kuban homed in on the century plant for his doctoral dissertation at Syracuse University. The plants are a curiosity — they live for 25 or 30 years, blossom once with large, beautiful flowers, and then die. Few biologists had devoted much research to the plant, and Kuban made it the topic of his doctorate in the early 1980s, spending four summers in the desert collecting data. His articles on century plants and hummingbirds were published in journals such as The Condor and The Southwestern Naturalist.

What might sound like a lonely and boring existence was nirvana for Kuban. And if he needed a break from the tranquility, he could cross the border into Mexico for some spicy comida and cold cerveza.

Sometimes the tranquility was broken in other ways. During his doctoral research, Kuban was driving a pickup truck down a narrow gravel road toward an isolated research site when he rounded a curve to find a group of bikers loitering just ahead. Never having seen anyone else in the area, he was shocked to find the scruffy group in his path. Slamming on his brakes, he kicked up a cloud of gravel and dust that sprayed the bikers. “They were pissed,” he said.

Facing a beating, Kuban sized up the situation. The bikers were taking pulls from a bottle of tequila, and nearby was an agave plant. As they grabbed him, Kuban told the men he was a biologist studying the tequila source-plant and that it was vital that he continue his research to ensure the golden liquid would remain bountiful for the ages.

“That was probably the quickest thinking on my part — I said that as I was being pulled from my truck and thrown on the ground,” he said.

Suddenly, he was a hero. The bikers picked him up, brushed him off, sat him down, and handed him the bottle. Kuban played up the tequila angle and wisely left out the part about hummingbirds.

Frightening in a different way was his run-in with a Washington politico in 1981. Kuban returned to his campsite one day to find a note from a park ranger recruiting him for an assignment. President Jimmy Carter’s energy secretary James Schlesinger was coming to Big Bend to search for a rare owl. Kuban, a noted bird-caller, was asked to ensure the owl made an appearance.

Later that day, a long line of limousines sporting American flags came winding down the dirt road and stopped. Doors swung open, and out stepped an entourage of 50 people — state representatives, judges, significant others, hangers-on, and security officers, led by the powerful Schlesinger, an enthusiastic bird-watcher. The plan: Travel five miles and 2,000 feet in altitude to an area called Boot Springs, to find the owl.

“They used every horse the park had,” said Kuban, who ended up walking. “They had one horse packed with nothing but liquor.”

By the time Kuban caught up with them, the party was well along. He figured the revelry would quiet down after sunset, when the nocturnal birds start their hunting. But even after the sun sank, the party continued at full tilt. At 10 p.m., the ranger whispered to Kuban to call in the owl so he could hustle the revelers out of the park. Kuban told Schlesinger he was ready.

“He yelled at the top of his voice, ‘It’s time to call in the owl!’” Kuban said. “I knew I was doomed.”

Apparently, the owls weren’t eager to amuse a bunch of rowdy VIPs. Kuban hooted his heart out to no avail. Schlesinger, known for his arrogance, wasn’t happy. “People started getting antsy,” Kuban said.

An intoxicated woman began flicking her flashlight on and off, and suddenly everyone caught a glimpse of what Kuban instantly recognized as a mastiff bat, similar in size and color to the rare owl.

“Schlesinger goes, ‘That’s it! That’s the owl!’” Kuban recounted.

After that, Schlesinger pulled out his checklist of birds and dutifully marked off the flammulated owl. And Kuban had a good — quiet — laugh.

Broken guitar strings were an early indication that something was physically awry with Kuban. Appropriately, they broke on stage at Panther Junction in Big Bend on June 30, 2006, during a benefit for the Big Bend Natural History Association.

The rugged paradise had inspired Kuban to write and record an album’s worth of songs in 2003. Proceeds from On the River Road: Songs From the Big Bend benefit the natural history group — and the album has sold well at the association’s bookstore at the national park.

“We’ve reordered those CDs probably six times,” Executive Director Mike Boren said. “We keep it displayed up front by the cash register, and it sells steadily.

“I think a lot of Joe — he’s a good man,” he said. “He’s always got a great smile and a good attitude.”

Musicians on River Road included Kuban’s older brother Frank on bass and younger brother John on lead guitar. A Terlingua radio station put it in the rotation, but the album didn’t garner much attention in these parts except at KNON.

“It’s held up well,” Obermark said. “There are a lot of CDs that, after you’ve heard them a few times, it’s more of the same old shit. This one has nice harmonies, and the playing is solid and understated and always serves the song rather than the other way around.”

In the summer of 2006, Kuban had been asked to play a benefit in Marathon to raise money for the Big Bend history group, so he arranged a mini-tour, including stops in Terlingua and Big Bend. But the first show didn’t go well for Kuban.

“He broke four strings in about 10 minutes,” John said. “Things weren’t working the way they should.”

Restringing a guitar disrupts a set’s momentum, and John was getting annoyed. His environmentalist brother Joe had never been a heavy-handed strummer, and John suspected a guitar malfunction. By the end of that tour, however, he knew the guitar wasn’t the problem. Kuban couldn’t play an F-chord, a toughie for beginning players but a piece of cake for old pros. And he was strumming too hard. His finesse was gone.

Brothers being brothers, this led to the usual bickering. Only later, after Kuban visited doctors, did they realize that the problem wasn’t a lack of practice. Nobody knows what caused Kuban to develop ALS, but some researchers believe it is associated with exposure to mercury, an element sometimes found in the century plant’s nectar at Big Bend.

“It’s the great irony that my life is being taken by something in the environment that I’ve worked so hard to protect for the last 30 years,” he said. “What I love is killing me.”

So Kuban began tying up loose ends. He started looking for a successor to take over his classes. And he decided to cut another album before it was too late. He’d written a dozen songs as a follow-up to his debut album, and he and his brothers started recording last year on a home computer at John’s ranch in East Texas. (As a musician myself, I was involved briefly in a couple of those early recording sessions.) There was no sense of urgency. Kuban could still sing and play, and nobody anticipated his rapid decline. Before long, however, he couldn’t fret a guitar at all; his speech became slurred, and he lost stamina.

By last summer, the brothers realized they needed to get Kuban’s vocals finished immediately. But with two songs remaining, Kuban’s voice finally gave out. These days, he uses a microphone just to be heard in class. He speaks in a weak whisper at times, and the sound can jump uncontrollably, like a kid whose voice is just beginning to change.

“We were already a little too late,” said John, who ended up patching together vocals from an early demo to finish the project. “You know when you’re not going to get a better take. If [the quality] keeps going down and down, you have to stop.”

There’s something poignant about listening to a man singing with what’s left of a failed voice, as on those final American Recordings from Johnny Cash. You sense an important trade-off, someone willing to expend valuable energy and maybe shorten their days in exchange for making a final statement to the world.

The album, It’s West Texas, by Kuban and the Lost Chizo Band, is expected to be available at www.agavemusic.com in the coming weeks. The quality of songwriting is stronger than ever. One song in particular explores his realization of a failing body and impending reliance on his wife.

DeLane is up for the task, being a physical therapist by trade and a doting mate by nature. It’s not the future she envisioned, of course. She and Kuban were married 10 years ago, and each had two children from previous marriages. They’ve only recently become empty-nesters and had been planning on doing more traveling.

“I had always said Joe would outlive me because he’s just always done everything properly,” she said. “He jogged and hiked and watched what he ate and was never overweight. It’s such a shock. It just takes the wind out of your sails.”

She began crying. But with her husband as an example, she pulled herself together quickly and apologized for her “leaky eyes.” Everyone from relatives to students to co-workers marvel at Kuban’s ability to stay upbeat, even though he can no longer do such simple tasks as buttoning his shirt.

“I’m sure any human in his situation, knowing full well what awaits him in future months and years, has moments of disillusionment, but I’ve never seen it, nor anything close to it,” his brother Frank said.

Kuban’s soulmate said the same thing.

“What’s been easier for me is that Joe is taking it so well,” DeLane said. “He’s always been the guy where the glass is half full. So many times illness will bring out the very worst in people. It has not with Joe. He’s a very spiritual man, and he is a wonderful scientist, and he has always been a positive person.”

His positivity has stretched all the way to Costa Rica, where he’s taken students since 1991 to study the rainforest and try and save a little piece of it. His classes stay in a village that once considered clear-cutting a road through the rainforest to allow children to travel to school, since the village’s own school was in disrepair.

“When you cut a road through the forest, you can kiss that forest good-bye,” Kuban said.

With support from Nolan officials, his students, their parents, and Tarrant County businesses, Kuban’s bunch replaced the roof on the school, added another room, installed the school’s first indoor plumbing, and donated countless soccer balls. They have given another $15,000 in the past decade to keep the school operating.

“And they can’t pull the wool over our eyes, because I come back each year and see how they spent the money,” Kuban said. “They know I’m coming back to check on it.”

The local school was resurrected, and the road was never cut. There are three plaques in Costa Rica honoring Nolan’s ecology class.

DeLane is proud of the man who introduced thousands of youngsters, including their own blended brood, to the importance of nature — a gentle and devout soul whose final lesson, it seems, will be about grace under pressure.

“I want people to know what a blessing it’s been to be married to this man,” she said. “We’ve had more experiences in 10 years than some people have in a whole lifetime. We thought we were going to have a lot more than that, but we are grateful for those 10 years.”

Typically, Kuban was worried about what would happen to his ecology program at Nolan — until recently. He teaches ecology classes at UT-Arlington, and his sights landed on Ellen Stringer-Browning, a graduate student studying Big Bend bobcats for her doctoral dissertation.

“I’ve been looking for someone to take over my course — looking and praying — and here she was in my class,” Kuban said.

Stringer-Browning knew of Kuban even before they met. She read about his Big Bend research and, having come across his CD, bought it as a Father’s Day present for her dad, the person who had introduced her to Big Bend years earlier.

Being asked to take over his classes next year at Nolan was an honor she couldn’t refuse. “This is an incredible program, and he loves it so much and has dedicated his life to it,” she said. “He wants to see it continued, and he knows I would continue it the right way.”

Still, the feeling is bittersweet, she said.

Kuban, though, is relieved to know someone bright and capable will carry on his legacy.

“Everything in life is timing, and she was the right person at the right time,” he said. “I can’t do it anymore.”

He feels now as though his class is in good hands — and so is he.

“Faith, and the fact I’m surrounded by so many good people, make this an easier task to bear,” he said.

You can reach Jeff Prince at jeff.prince@fwweekly.com.

More information: http://www.quantumshift.tv/v/1198253034

Email this Article...

Email this Article...