Students at Daggett Middle School get computerized lessons — and the benefit of a veteran math teacher. (Photo by Scott Latham)

Students at Daggett Middle School get computerized lessons — and the benefit of a veteran math teacher. (Photo by Scott Latham)

|

|

The teacher

‘was reduced

to being the

Shell Answer

Man ... .’

|

Students go through the I CAN Learn program at their own pace. (Photo by Scott Latham)

Students go through the I CAN Learn program at their own pace. (Photo by Scott Latham)

|

|

‘The ICL program is successful because it works, not because of media coverage.’

|

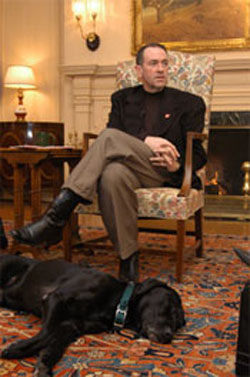

Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee called school administrators to hear a pitch from JRL. (www.arkansas.gov)

Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee called school administrators to hear a pitch from JRL. (www.arkansas.gov)

|

|

‘Our kids simply weren’t prepared by ICL to pass the state exam.’

|

Askey: I CAN Learn and other computerized programs are ‘dumbing down’ math instruction.(www.math.wisc.edu)

Askey: I CAN Learn and other computerized programs are ‘dumbing down’ math instruction.(www.math.wisc.edu)

|

Trustee Juan Rangel said the superintendent never arranged school board trips — except to New Orleans. (Photo bt Scott Latham)

Trustee Juan Rangel said the superintendent never arranged school board trips — except to New Orleans. (Photo bt Scott Latham)

|

Veteran teacher Cruz Gracia likes I CAN Learn but says it will never work without teachers’ participation. (Photo by Scott Latham)

Veteran teacher Cruz Gracia likes I CAN Learn but says it will never work without teachers’ participation. (Photo by Scott Latham)

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

I Can Earn

A costly and controversial math program

is getting failing grades around the country.

By BETTY BRINK

A qualified teacher with a good textbook will beat a computer math program every time. — Jerry Dancis, mathematics professor, University of Maryland

Cruz Gracia’s seventh-grade math class at Daggett Middle School was about to begin. The veteran teacher hushed her chattering brood and flicked off the overhead lights. “Time to get to work,” she said. In most classrooms, plunging a roomful of 12-year-olds into sudden darkness would likely trigger a round of rowdiness and giggles. Not here.

Gracia’s kids were not seated at traditional desks facing the teacher. They sat in a cramped room facing each other in two laboratory-style rows of specially made “work stations” designed to hold a computer, a monitor, a mouse, and a keyboard. Each of the 30 stations had a glass top with the monitor underneath, tilted up. The eerie flickering lights of computer screens began to fill the darkened room as the pre-algebra students quietly booted up their computers and waited for Gracia’s signal to start their lessons. As Gracia called roll, she also gave out lesson numbers, and the kids, one by one, donned headphones, typed in the lesson number, and watched as an animated instructor came into view who would take each through his or her individual lesson and a multiple-choice test at the end.

The I CAN Learn computerized math software program was in full swing. Gracia, a teacher with the district for 30 years, has been using it to teach seventh-graders at Daggett since 1999. ICL algebra and pre-algebra labs are now installed in more than 200 Fort Worth classrooms for grades five through nine, making this district by far the largest customer of JRL Enterprises, the New Orleans company that produces the software. By the end of 2008, when JRL’s contract expires, the district will have paid the company $16 million under contracts negotiated by former superintendent Thomas Tocco, who once touted the program as being so superior that kids could use it without a teacher — a notion that upsets Gracia.

“The classroom teacher is the key to making this program work,” she said.

To Fort Worth schools trustee Juan Rangel, who is an opponent of ICL and voted against extending the contract to 2008, Gracia is the “true essence of a dedicated educator. She can take anything and teach with it, and children will learn,” he said. “She could make any program work.”

But even with the efforts of teachers such as Gracia, the chances of making this controversial program work at this late date may be about as remote as solving the Riemann hypothesis.

In the last several months, the program has been at the center of a prairie fire of controversy over issues ranging from its enormous costs to a possible FBI probe into the Tocco administration’s use of federal funds to pay for it. Its curriculum still doesn’t match the state’s “essential skills” algebra standards even though the company has been trying to fix that major glitch since day one. The three years remaining on the contract may be axed by the district’s temporary superintendent, Joe Ross, if a cost-benefit analysis now being done by an Austin consulting company comes back with negative findings.

Around the country, educators once enamored with JRL owner John R. Lee’s computer-teaching brainchild (dreamed up by a man with no background in education or mathematics) are now dumping the program. They cite its expense and its basic failure to do what Lee promised: raise their students’ math test scores enough to get their districts off the No Child Left Behind hit list. The program hasn’t managed to do that here, either — the 2004 TAKS test results show Fort Worth students’ math passing scores still a dismal 16 percent lower than the state average.

A math director in a California district resigned over his district’s decision to buy the program. The Texas Education Agency’s director of mathematics says programs such as I CAN Learn should be used to augment traditional instruction, never as a teacher replacement. Queries to other districts that are using the program found only one pleased with the results out of those who responded.

Ethical questions about the program abound, from the fact that the only published evaluation of the program was done by a researcher with economic ties to JRL, to Tocco’s lobbying of Texas congressional members to give the company millions in federal grant dollars, to an Arkansas governor’s heavy-handed application of influence on behalf of I CAN Learn.

Academic mathematicians see its use as a “dumbing down” of math education — one called its touted benefits a “big lie” — and have mounted campaigns to keep it off the federal government’s list of recommended programs. Some see it as an insidious attempt to replace classroom teachers. Others cited the failure of the curriculum to meet their states’ math standards. And all question its lack of independent, “scientifically rigorous” research.

With so much criticism and so little research, how did Lee get a foothold in so many school districts? And if the districts have failed to benefit from his program, who did? The answer may be found by following the money trail of a relatively unknown entrepreneur who has been bailed out of financial disasters more than once by big lawsuit settlements, influential lobbyists, key national politicians, and obliging governors whose campaign coffers for almost a decade have been swelled with generous amounts of cash from a former oil transporter who woke up one day with a brainstorm about algebra.

Twenty years ago John R. Lee was busted flat in Galveston, the victim, he has said, of a conspiracy by Mitsubishi Corporation and others to blame him for a fatal rail car explosion that cost him his company. By 1990 he was the comeback kid, with a major lawsuit settlement in his pocket and a dream of changing the way the nation teaches math to its kids.

In interviews with Gannett Weekly and the New Orleans Times-Picayune, Lee told reporters that in 1986 he was a Galveston businessman, owner of an “international trade company” whose railroad cars were used to move petroleum products. Lee claimed employees of Mitsubishi borrowed some of his cars without his authorization. One exploded, killing a worker and injuring another. The Japanese company and others, Lee alleged to reporters, signed a contract agreeing to blame Lee for the mishap. It ruined him financially, Lee said. He sued and in 1990 won a $16.7 million judgment against the company; Mitsubishi appealed, and Lee settled out of court for an undisclosed amount.

Lee recalled a juror saying he hoped the businessman, with such a nice sum, would give something back to the community. Lee said he had just the thing: He had developed the idea for I CAN Learn after hearing that one of the government’s education goals was to introduce technology into every classroom. “Suddenly the idea popped into my head that each kid should be allowed to work at his own level by using computers,” he said. All he was waiting on, he told Gannett, was the seed money to get started. And Mitsubishi had come through with that. By 1994, Lee was in New Orleans, the owner of JRL Enterprises, and his dream math program was in production.

“I have one job,” he told the Picayune, “that’s to educate the children.”

By 1999, the New Orleans paper reported, JRL Enterprises had grown from a handful of employees to about 75. Lee said he would be expanding to 500 to 1,000 employees within a year. The firm reported gross revenues of $10 million for two consecutive years. Lee had also begun to play in the political big leagues; he was one of Louisiana’s biggest contributors to local and national campaigns, and he hired the powerful Bob Livingston, who’d represented Louisiana in Congress for 20 years, to lobby for his company in Washington.

But in 1999 Lee’s company also suffered a setback that almost destroyed him again. Sales had hit a slump; he was in default on a $4 million loan with New Orleans First Bank & Trust, and the bank seized his assets and took control of the company. Some of his high-powered board members resigned, including former Tulane president Eamon Kelly. Lee was kicked out of his office; suits and countersuits were filed. The picture was grim — until Tocco entered from the wings.

That year Tocco negotiated the first contracts to install I CAN Learn in Fort Worth classrooms. Soon, he had turned an initial one-year, $3 million commitment for 13 classrooms into a $16 million commitment for installations in 203 classrooms. Lawyers for bank directors being sued by Lee told Fort Worth Weekly that the Fort Worth contract helped pull Lee out of his financial mess. In a deposition taken in one of the lawsuits, Tocco was asked why he bought the expensive program. It was on the advice of an old friend, Russell Protti, Tocco said, a former superintendent in Louisiana whom he trusted. At the time, Protti was also working as a lobbyist for Livingston, helping him with his education client, JRL.

By 2001, Lee and the bank had settled out of court, and Lee was in control of his company again. The financial slump, however, didn’t seem to have had an impact on his political gift-giving.

The Weekly’s search of campaign contribution records shows that since 2000, Lee, his wife, and key JRL executives have contributed more than $500,000 to politicians on both sides of the aisle, plus giving thousands more that ended up in governors’ campaign coffers and more than $205,000 going to “527” committees — the tax-exempt advocacy groups known as “stealth PACs,” which may legally engage in political activity through unlimited soft-money contributions as long as they don’t endorse specific candidates. The Center for Public Integrity in Washington, D.C., lists JRL Enterprises as the top contributor from Louisiana to 527s between 2000 and 2004.

Lee’s payments to lobbyists have been even higher — Livingston alone has received almost a million dollars since 1999, according to federal lobbying disclosure records. In Livingston’s last two years in office, before he confessed publicly to adultery and tearfully resigned his congressional seat, Lee contributed $10,000 to his campaign accounts. Shortly after Lee hired him, Livingston bragged to the New Orleans media that he had secured a $9 million grant from the Department of Education for the I CAN Learn program that year.

Most of the incumbent congressional beneficiaries of Lee’s largesse received the maximum contributions allowed under the law. They also shared one other trait: They were members of either the Senate or the House appropriations committees, the folks who have kept JRL afloat with education grants totaling more than $45 million between 1998 and 2005. On the House side, they included Texas’ Henry Bonilla, Florida’s Bill Young, and David Obey of Wisconsin. Senate committee members included Thad Cochran of Mississippi, Arlen Spector of Pennsylvania, Iowa’s Tom Harkin, and Louisiana’s Mary Landrieu. Lee has also given generously to U.S. Rep. William Jefferson of Orleans Parish — whose school district is a large purchaser of I CAN Learn. Jefferson sits on the Budget Committee and is a member of the Congressional Black Caucus.

In 2003, Lee was the third-largest contributor to the Republican Governors Association. In 2003 and 2004, his contributions to that group totaled $210,000. The Democratic Governors Association got $50,000 in 2003. And while no individual governors show up on Lee’s contributor lists, the RGA and the DGA both raise money for the election of their party’s candidates for governor.

Politicos aren’t the only ones to receive star treatment from Lee. In April 1999, Fort Worth school trustees Jean McClung and Judy Needham and school administrators Nancy Timmons and Roy Hudson were Lee’s dinner guests in New Orleans, part of a trip arranged by Tocco so they could tour a couple of schools with I CAN Learn labs. In a memo released under an open records request, Tocco wrote to the quartet that “Hotel reservations have been made for you at the Le Pavillon Hotel” (at a cost of $189 a night) and that John Alvendia, JRL senior vice president, had arranged to “take you to the Commanders Palace. Jackets are required by men.” The Palace is one of the Crescent City’s most expensive restaurants. When asked how often the superintendent arranges trips for trustees, Juan Rangel, who was not invited, said, “Never, to my knowledge.”

In fact, over the next three years, school district employees were keeping the airlines busy with trips to New Orleans. Tocco made at least four over a two-year period. Math coordinator James Goodloe, who was instrumental in implementing the program here, until he quit last year to go to work for JRL, made several trips. So did his Fort Worth co-worker on the ICL project, Barbara Black. Two of their trips to New Orleans were listed on school vouchers as “Staff development, no expenses incurred.” Expenses were paid by JRL Enterprises, the voucher noted. And at least one math teacher was sent by Tocco to evaluate the program.

Dana Chadwick, director of secondary education for the Little Rock, Ark., school district, also was treated royally by Lee when he accepted an invitation several years ago for a similar New Orleans tour. After that trip, his district installed ICL, with federal grant money providing the majority of its funding.

A much more surprising invitation arrived last year, however: Chadwick and other school administrators were called to a meeting with Arkansas Gov. Mike Huckabee. When they were ushered into the meeting room, Chadwick said, Huckabee, JRL vice president John Alvendia, and another executive from the company were there. Alvendia put on a presentation about I CAN Learn, and the governor made an appeal to the group, urging them to “give [the program] a positive look.”

Huckabee’s action was “totally wrong, totally unethical,” said Larry Shaw, a former teacher and long-time head of the United Educators Association. “A politician, especially a non-educator, should never be out shilling for a private company trying to sell its product to the schools,” he said. “Only educational professionals should judge the quality of a program before it’s bought by a district, whether it’s a textbook or a computer program or an on-line program.

“We’re going to see a lot of this in the future,” he said, “as more and more businesses catch on that there is money in education. And the companies will give to the politicians that can help make it happen.”

Gov. Huckabee’s charm was lost on Chadwick for the same reason that ICL’s appeal seems to be fading in many quarters: When the federal money runs out, the program has costs that are too high and a success rate that’s too low.

Chadwick, for instance, has had the program in place in two middle schools and one high school for four years, but he’s not renewing the contract. While a lot of kids have made gains, he said, the results overall have been “spotty.” The schools’ improvement scores have not gone up enough in three years to meet No Child Left Behind standards. Under that law, pushed through by President Bush not long after he took office in 2000, students in schools that fail to meet their state’s standards after two years can demand a transfer to a better school, and the district must pay the cost. The offending school also loses federal tax dollars for each child who transfers.

A major reason for ICL’s failure in Arkansas, Chadwick said, is that the program’s tests are multiple choice, with no writing component. About half the problems on Arkansas math tests require written responses. “Our kids simply weren’t prepared by ICL to pass the state exam,” he said.

The other reason he’s not renewing, Chadwick said, is the “extraordinary” cost. The federal money’s gone, “and we are poor, poor, poor.”

In Sacramento’s semi-rural Grant Joint Union High School District, ICL was implemented by the district’s superintendent “over the objections of the math department chairs of his five junior highs and four high schools,” Darren Miller said. He was the district math chairman at the time, he told the Weekly. It cost $4 million, of which $3 million was paid with grant money, and it turned out to be “a lousy implementation of a mediocre product,” Miller said. Hardware problems were bad enough (glare from the glass tops, cramped space) but “pedagogically, it was a nightmare.” The teacher, he said, “was reduced to being the Shell Answer Man and the class IT guru. ...Watching a video to learn algebra is not a program for someone who thinks of education as being a social process between individuals.” After a year fighting it, Miller resigned in 2001 rather than have to deal with “that monstrosity.”

That same year, the California State Board of Education refused to recommend the program for its schools. The board found that ICL failed to “provide thorough instruction on the standards and the mathematics content described in the framework.” This year Grant Union has dropped the program, said Brent Givens, senior education coordinator for the district. “It no longer fit our needs,” he said.

In Atlanta, however, Kathy Augustine, head of instruction for the city’s school district, thinks ICL is working just fine. She wrote that ICL was implemented there as a pilot program at five middle schools in 2001 at a cost of $750,000. Their studies show that students and teachers like the program, that 91 percent of the students at one school met or exceeded the state’s algebra standards, but that — while test scores were impressive in the seventh and eighth grades — the ICL students did no better at that level than the traditionally taught students. “Overall,” Augustine wrote, “the district is pleased.” It is currently considering whether to expand it to more schools.

JRL’s web site lists Dallas as the only other school district in Texas with I CAN Learn labs. However, the Dallas schools’ director of media communications, Ivette Weis, said, “We do not use I CAN Learn; it’s not on the district’s recommended list.”

“It’s a serious mistake to think you can replace teachers with a computer,” said Richard Askey, a retired math professor from the University of Wisconsin. “If you want to get students really interested, there must be inspiration from a teacher.”

Askey, a member of both the National Academy of Sciences and the Department of Education’s expert panel set up to evaluate new math technology programs, is an outspoken critic of computerized programs such as I CAN Learn.

Askey stirred a world of controversy in education circles six years ago when he and 200 other top mathematicians and scientists from across the land ran a full-page “open letter” ad in the Washington Post calling on then-education secretary Richard Riley to withdraw the government’s endorsement of new math programs “that experiment with non-traditional teaching methods,” calling them a “dumbing down” of math instruction. I CAN Learn was one of those programs, Askey said.

A source high in Texas education circles who asked to remain anonymous said the “bad publicity” the company has been getting — specifically in the Fort Worth papers — is beginning to hurt its ability to sign up new customers.

Lee refused to comment to the Weekly. But an e-mail from his lawyer, Greg Beuerman, said that the program is successful and that the controversy is not even widely known outside Fort Worth. “The ICL program is successful because it works, not because of media coverage,” Beuerman said.

Vic Hovsepian, professor of mathematics at Rio Hondo College in Whittier, Calif., told the Weekly via e-mail that he evaluated the program a year ago. “Simply stated, I gave it a THUMBS DOWN,” he wrote, calling JRL’s glowing promises of the program’s benefits “a big lie.”

Hovsepian was especially incensed over the company’s insistence that participating districts buy the hardware (desks, chairs, computers, etc.) along with the software — which raises the cost as high as $300,000 for a unit of 30 work stations. JRL refuses to sell its software program on a disc that could be popped into any existing computer. “Do I have to tell you more!!!.” Hovsepian wrote.

That was roughly the same reaction that a Fort Worth schools worker had a decade ago, when she attended a vendor’s show- case of programs being offered to the district and saw a demonstration of I CAN Learn. The worker, who was involved with providing technology support to the district, asked that her name not be used.

“I thought it was a joke. I couldn’t believe it,” she said. “It was audacious to say that a work station would cost $30,000, when I knew for a fact that a top-of-the-line work station could only reasonably cost $3,000 and the furniture little more than that. A work station costing any more than that would be pushing it. And then to learn that you don’t even own the software, that you’re just paying for a license which must be renewed, was shocking.

“I think there was general confusion among the teachers and principals,” the technology worker said. “It seemed like the software met objectives that they were trying to meet, but it was so expensive. It was almost as if the expense made the program seem more viable. ... It seemed as if people were thinking that if the program was that expensive, they must have research to back it up.”

If a district chooses not to renew the software contract, it can keep the desks and computers, but several told the Weekly they aren’t sure just what they can do with them because they are specifically designed to work with the I CAN Learn software and teaching method.

Other Fort Worth educators worry about what the expensive program doesn’t come with — textbooks or workbooks. In an interoffice memo sent Oct. 15, 2003, to a principal and assistant principal at Riverside Middle School, two teachers who were using the I CAN Learn program formally requested more funding and expressed their concerns about the state of math lab learning and the undue burdens it placed on them.

“The I CAN Learn classrooms currently do not have a formal textbook nor workbook that is available for use by the students, to assist their learning, in addition to the computer lessons with which they are presented,” the teachers said. To bridge that gap, teachers and other district workers had cobbled together their own version of a workbook. Adding insult to injury, however, the teachers often found that, in this modest effort to help make the multi-million-dollar program work, they had to spend their own money on the paper and folders for the workbooks.

Richard Innes, an education analyst with the Bluegrass Institute for Public Policy in Bowling Green, Ky., is concerned about the research connected to I CAN Learn. “The most compelling studies come from researchers with no vested interests in the outcome,” Innes said. “While it is not inconceivable that honorable individuals could do good research despite vested interests, there is always a cloud of doubt in such cases. Independent verification of such research by others with no interest would strengthen the impact. ...

“Many people still don’t understand the difference between rigorous, independent scientific research and advocacy,” he said.

On JRL Enterprises’ web site, the company states that it uses “rigorous scientific methods of analyzing data collected from all of its sites. ...” Since 1995, the web page says, “dozens of studies have shown the effectiveness of I CAN Learn [and] in nearly every case, greater student achievement has been reported, especially for poor and minority students. ...” The site also directs the reader to the Department of Education’s What Works Clearinghouse, which purports to be “a trusted source of scientific evidence of what works in education,” to view the studies on I CAN Learn. The site currently lists only one report on I CAN Learn that WWCH says meets its standard for a “scientific and independent evaluation.”

The report is authored by Peggy Kirby, a New Orleans professional evaluator and former professor at Tulane University. What Kirby — and JRL — fail to declare in any of her “scientific evaluations,” however, is Kirby’s financial connection to JRL. She is a paid consultant for the company today, and for two years — from 1999 through 2001 — she was a direct employee of JRL, involved in developing the I CAN Learn software.

All of Kirby’s “independent” studies conclude with a recommendation that the districts studied should continue to use the program.

Two of the Kirby studies were done for schools in other states and were used by Tocco to promote the program here; one study has been done for Fort Worth and was based on state tests for the years 2000-2004, which show “mixed results.” She nonetheless recommended that “given the promising results ... in other states” the Fort Worth district should continue with the program.

However, others such as Askey point out that the two out-of-state studies are too small and limited in scope to be of any value. One was based on a six-week study of a class of 204 students in Georgia, the other on a group of students in one Orleans Parish school during a single school year. In both studies, Kirby cited “empirical evidence” to show that the districts should continue to use the expensive software.

And when Askey tried to pull up the Kirby study on the Clearinghouse web site, he said he was met with a message that said “Coming soon.”

When I CAN Learn got a “promising” designation from the Department of Education’s expert panel six years ago, based on Kirby’s study, JRL quickly put the good news on its web site. Askey, who was on the panel, was not pleased. The program, he said, should have never been recommended, because it lacked any independent evaluation. To use Kirby’s studies flies in the face of reason, he said: “Evaluations should be independent of the program.” The Department of Education has since removed I CAN Learn from its list of recommended programs, without explanation.

As for computer programs as teaching methods, Askey said, “Sure, some students will do it on their own, but they won’t get the excitement, the deeper understanding of mathematics” that can come only from the unique contact between an inspired teacher and his or her student.

Paula Moeller, director of mathematics for TEA, said the agency does not recommend any specific math programs. However, she said, it is her position that computer math programs should be used only to supplement and help enrich traditional math teaching methods. “I don’t think these programs will ever take the place of teachers,” she said, “but a lot of teachers fear that they will.” Too many of the math computer programs, she said, are about “skills and procedures” and not about understanding the concepts.

Cruz Gracia believes she still gets that “unique contact” by combining traditional math teaching methods with the ICL program. Her brightest students quickly master the program, she said, and she moves them on to a math honors program. The “lagging behind” students who are on different levels need an experienced teacher who can quickly shift from one math concept to another, she said. “You have to know your math to do that.”

JRL promotes ICL as a program where “the computer is the teacher.” Indeed, in some Fort Worth classrooms, it has been overseen by teacher’s aides with only high school diplomas. Gracia finds this, and Tocco’s comments about kids not needing a teacher for ICL, disturbing. She loves the program, she said, and wants the district to keep it. But the notion that any computerized teaching method doesn’t need a live teacher competent in the discipline is an insult, Gracia said.

Dressed in jeans and a brown sweater — it was “casual Friday” at the school — the tall, slender Gracia was constantly in motion during the 45-minute class, moving from station to station, asking questions, probing the students for answers, urging them to think, her face lighting up with joy when a kid aced a quiz. And just as in any traditional classroom, Gracia gives homework twice a week and requires her students to take notes and to give her written explanations for their answers. She uses the blackboard often. “I say to them, ‘Look up here, at me, now it is time to look up from the computer and listen to your teacher.’”

Brooke Gray contributed to this report.

Email this Article...

Email this Article...