|

|

|

‘We got caught between \r\ntwo nations, and we’re \r\npaying for it.’

|

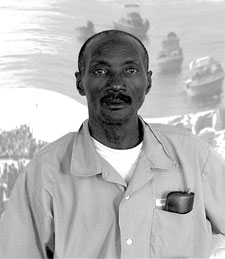

Marcelino Gonzales: ‘I’ve done my time. I’ve been in prison seven years for nothing.’(photo by Dan Malone)

Marcelino Gonzales: ‘I’ve done my time. I’ve been in prison seven years for nothing.’(photo by Dan Malone)

|

|

‘From what I saw \r\nin the ocean, 300 to 500 \r\npeople died.’

|

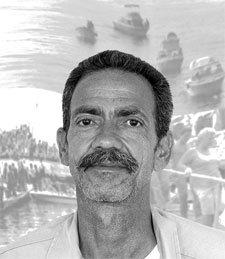

Jorge Camdesuner Columbie: ‘No matter how many letters you write, you don’t have an answer.’ (photo by Dan Malone)

Jorge Camdesuner Columbie: ‘No matter how many letters you write, you don’t have an answer.’ (photo by Dan Malone)

|

|

‘I pray every day ... \r\n“God, how can you\r\nnot hear us?” ’

|

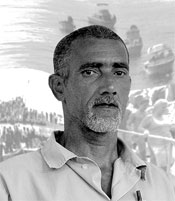

Alfredo Pomares: In Cuba, ‘if I serve two years, I’ll be out. Here, I don’t know.’ (photo by Dan Malone)

Alfredo Pomares: In Cuba, ‘if I serve two years, I’ll be out. Here, I don’t know.’ (photo by Dan Malone)

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Rotting in Jail in the Land of the Free

Nearly a quarter-century later, Marielitos are still looking for justice.\r\n

By JULIAN AGUILAR and DAN MALONE

They languish in American custody, although many stand accused of no crime other than perhaps having dark hair and skin and sharing a nationality with a leader who rails endlessly against America’s evils. Abandoned by the country of their birth, they have sat rotting for years now behind bars, imprisoned without trial by a nation whose proudest claims are to freedom, civil liberties, and the rule of law.

Some have serious crimes in their pasts — but even those debts to U.S. society were paid long ago. Many others were originally arrested for minor crimes — throwing a rock through a windshield, buying a set of stolen stereo speakers — but still have been kept in prison for years after serving out their original sentences. The government keeps them shrouded in secrecy, refusing to give out their names or the details of their cases, sometimes banning photographs and restricting interviews. Lawyers willing to take their cases are hard to find. Some prisoners have gone for a decade or more without a visitor. One man was so desperate to make contact that he used his own blood to write a letter to a journalist. “Abuso, no lapis, mi sangre, dies y seis y medio años,’’ he wrote. Abuse, no pencil, my blood, sixteen and a half years in an immigration prison. Many fear they will never see another day of freedom.

These are not prisoners in the war on terror, however — the U.S. government’s hijacking of these people’s freedom began long before 9/11. In fact, rather than being held in Cuba, they are being held — many of them in Texas jails and prisons — because they are from Cuba. And they came here, not looking for opportunities to wreak a nightmare of terror on America, but because America, for many, was their dream. They are Marielitos, part of the tidal wave of refugees who braved a deadly crossing from Cuba 24 years ago to reach — they thought — sanctuary in a country whose president had promised to welcome them “with open arms.” They are all but forgotten ... all but.

Next month, the U.S. Supreme Court will consider whether the detention of a Mariel Cuban named Daniel Benitez is legal, a case that could have widespread repercussions for perhaps a thousand others now being held in the United States. Sometime next year — perhaps around the 25th anniversary of the Mariel boat lift — the court will rule. And, perhaps, for the first time in years, life may change for these prisoners scattered through jails and federal lockups across Texas and several other states. Men like Rafael Gonzalez Puebla, and Pedro Creache Gainza, and Daniel Benitez.

An ocean of shipwrecked dreams and sunken hopes separates Rafael Gonzalez Puebla from the day some 25 years ago when he arrived in the United States. From a drab, small room at a federal prison outside Bastrop, Gonzalez recently summoned the distant memories of the 90-mile trip from the Port of Mariel in Cuba to the Florida Keys. He was one of almost 125,000 people who risked their lives in rickety ships and boats to escape Cuba and start a new life in America.

The sea was too rough, Gonzalez remembers, and the boat far too small for the 300 people aboard. He watched helplessly as waves crashed across the deck, one after another, washing his shipmates into the Gulf of Mexico where they would be snagged by the circling sharks, pulled into the blackness, screaming and gasping for a final breath.

Removing his thick, dark glasses and mopping tears, he recalled how he escaped the sharks only to be swallowed whole, decades later, by an equally emotionless bureaucracy in the United States.

“We could see them fall [overboard] and cry for help,’’ Gonzalez said. “Nobody could do anything for them. The sea was full of blood and was turning red.’’

More than a thousand vessels made similar crossings during a six-month period in 1980. The Mariel boatlift, according to histories on file with the Supreme Court in the Benitez case, was rooted in growing political unrest in Cuba during the late 1970s and then-President Jimmy Carter’s desire to improve diplomatic relations between the two nations.

In April 1980, six Cubans, wanting nothing more than to live elsewhere, dodged a hail of gunfire from Fidel Castro’s security troops to break through the gates of the Peruvian embassy in Havana. When the Peruvian government granted the group political asylum, Castro startled the world by announcing that all other Cubans wanting to leave the country should gather on the embassy grounds. What began as a group of six soon swelled to more than 10,000, and Castro sent them to the Port of Mariel, from which to seek refuge, not in Peru, but in the United States.

Before long, the sea between Cuba and the Florida Keys was bobbing with a virtual armada of only marginally seaworthy vessels, each heavily freighted with human cargo. As the small fishing boats and shrimpers began to make their way across the Gulf of Mexico, Carter, who was seeking re-election, was asked how the U.S. would respond to the surge of immigrants. His response, which many imprisoned Mariels can quote today, made headlines across the U.S. and Cuba. The president pledged “an open heart and open arms to refugees seeking freedom from Communist domination and from economic deprivation brought about primarily by Fidel Castro and his government.’’

Carter’s welcoming words encouraged even more Cubans to pour into the Port of Mariel, and boats containing dozens or hundreds of refugees continued to stream toward Florida. By the time Castro closed the port in September, almost 125,000 people had arrived in the United States.

Most of the desperate men, women, and children on the boats — human flotsam in what would become a great 20th-century exodus known as the Freedom Flotilla — were law-abiding citizens in Cuba who eventually built productive lives for themselves in the United States. Others, like Gonzalez, damned by bleak circumstances beyond their control or their own poor choices or dark impulses, were destined for a life perhaps worse than the one left behind. They made it to America only to stumble and fall, often violently. Eventually they broke the laws of the nation that welcomed them and were sent to prisons, including a handful of facilities in Texas, from which they have yet to emerge. Many have been detained for more than a decade.

Gonzalez said he was born in 1942 in Manzanillo, about a 12-hour drive from Havana. In Cuba, he stole the basics of life — beans, rice, lard, and bread — from one of Castro’s government-owned groceries. In the U.S., he made a living, when he could, as a custodian in parks, movie houses, and schools. He’s illiterate, and it’s not clear whether he came to the United States with the other Mariels or a little before. Whenever it was, he survived his voyage only to fail on the streets. Gonzalez said he was sentenced to three years for possession of cocaine, then again for molesting a 12-year-old girl, a crime he says he did not commit. He said that this time he’s been locked up for more than 20 years, about half of that time in the Bastrop Federal Correctional Institution in central Texas, where he is an immigration detainee.

Regardless of their crimes, the Mariel boat people being detained by immigration officials today have served whatever prison sentences they were given. Had they come from virtually any other country, they likely would have been freed long ago, as have other criminals who have made amends to society. But many Mariels remain behind bars because of quirks in immigration law and strains between the governments of the United States and Cuba.

Under U.S. immigration law, non-citizen residents of the United States, whether here legally or illegally, are subject to deportation if they commit a crime, or even for crimes committed long ago, a controversial law that has torn apart immigrant families across the country. If the Marielitos had come from Mexico or Poland or Japan and committed crimes, they would have served their sentences in the U.S. and then been sent back to their native countries.

But Cuba won’t take the Marielitos or other Cubans back. With no place to deport them to, U.S. immigration officials refuse to release many of them back into American society. Cuban Review Panels, made up of immigration agency officials, decide who goes free and who stays behind bars. But prisoners complain that that process is as capricious as the rest of their treatment in federal custody.

And so they sit, in a legal no-man’s land populated by all-too-real people — although they are people, it seems, the U.S. government would like for everyone to forget.

“In 1980, we got caught between two nations, and we’re paying for it,” one Mariel said.

Like prisoners in the war on terror, the Mariels still behind bars in the United States are treated like dangerous secrets by the government. Unlike terror suspects, who have been the subject of intensive media coverage and international outrage, Mariels have faded from public memory, and visitors are rare. The recollection of their plight is dim even within the bureaucracy charged with their oversight: The person answering the telephone in the public affairs office of Immigration and Customs Enforcement in Washington didn’t know what a Mariel Cuban was when a reporter telephoned.

Even their numbers are murky. Immigration officials did not respond by deadline to questions about how many Mariels are behind bars or how many may have been released in recent years.

“It’s hard to know what the numbers are,’’ said Mark Dow, who wrote about Mariels in his book, American Gulag: Inside U.S. Immigration Prisons. “It seems as if there are somewhere around a thousand in immigration detention.’’ Mariels, he said, are in a “legalistic black hole’’ with few interested in their fate or welfare. “Unfortunately they are often considered unsympathetic even by some immigration advocates,’’ he said.

Dispersed in small groups inside federal prisons, immigration detention centers, and county jails across the country, they are difficult to identify. In North Texas, perhaps a dozen have been held in recent years at facilities in Cleburne, Fort Worth, and Seagoville. But the federal government, with the Orwellian claim that it is protecting their privacy, has refused to identify them. Even when their identities are known, the government makes it difficult to communicate with them. They are frequently shuffled from one facility to another. Requests for interviews or information about the prisoners sometimes languish, like the prisoners themselves. When interviews are arranged, they are sometimes monitored by prison officials, and prisoners are not permitted to show reporters personal papers or documents related to their cases. Photographs are often forbidden.

Fort Worth Weekly identified, interviewed, and exchanged letters with about a dozen Mariel Cubans being held in prisons or jails in Texas. Because few records on these men are publicly available in Cuba or the United States, details of their stories could not be verified. Many say their situation is worse than that of the suspected terror suspects that the United States is holding in Cuba at the naval air station at Guantanamo Bay.

Pedro Creache, now 50, said he was first jailed as a juvenile in Cuba for stealing a bushel of bananas. He’s done time in the States for selling two crack rocks to an undercover cop and for not showing up at a work-release program after his car broke down. He finished his last criminal sentence five years ago, he said. Rather than being released, however, he was simply moved to the custody of immigration officials.

“I am not a terrorist,’’ Creache said. “We are not the same. We are not against the United States. I recognize a lot of Mariels [have] committed crimes, but I am not like them [the terrorism suspects].’’

Daniel Benitez landed in Key West on June 26, 1980. Jimmy Carter may have pledged to welcome Benitez and others with an “open heart and open arms,’’ but under U.S. law he had arrived in this country illegally. So Benitez wasn’t granted citizenship or even permanent legal residency status. Instead, he was “paroled” into the United States — allowed to go free but not technically “admitted” to the country.

In 1983, he was placed on probation for three years after being accused of buying stolen stereo speakers. Ten years later, he and two other men were indicted for an armed robbery that netted $600. For that, Benitez drew 20 years — punishment that morphed into a virtual life sentence.

While Benitez was in prison, court records show, the government revoked the immigration parole he had been granted in 1980. An immigration judge subsequently reviewed his case and ordered him deported.

Benitez finished his prison sentence on July 27, 2001, having served about 8 years of the 20 that had been handed him. Instead of being released, however, he was turned over to INS for deportation. And ever since, he’s been in the Mariel limbo. Immigration officials have orders to deport him but cannot because Cuba won’t take him back. So instead, the government has indefinitely extended his detention.

In the summer of 2001, Benitez was among some 3,000 foreigners being held by immigration officials because their homelands would not take them back. Immigration officials called these prisoners “indefinite detainees.’’ The prisoners had another way of describing themselves: they were “lifers.’’ Each was essentially given more prison time without being charged with a new crime or tried before a judge or jury.

Immigration officials said most such lifers came from nations that had long- simmering problems and no repatriation agreements with the United States — countries such as Vietnam, Laos, and Cuba. And most of those being detained, according to immigration officials, had been convicted of serious crimes in the U.S. and had served time in U.S. prisons. Immigration officials claimed that the only reason they detained these prisoners after they completed their prison sentence was to protect the public from violent criminals.

As journalists around the country began to examine the identities of the lifers, a different picture began to emerge. At least a dozen of the “hardened criminals’’ from whom the immigration agency was protecting the public turned out to be asylum-seekers who had broken no law other than showing up on U.S. shores without proper paperwork. At least one man, now released, had been held for seven years despite never having been tried for any crime in the United States.

Contrary to immigration claims that the lifers came from only a handful of nations, records revealed that they actually came from almost 70 countries around the world. And while many had in fact been convicted of serious crimes, the immigration agency’s own records, obtained under the federal Freedom of Information Act, showed that more than 300 prisoners had been convicted of no crime requiring their detention in the first place. It began to look as though the government’s stonewalling tactics were intended to protect it from embarrassing revelations rather than defending the privacy of prisoners that no nation on earth wanted.

Good news seemed to follow. A month after Benitez was picked up by immigration agents, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that federal officials could no longer indefinitely detain foreigners simply because they could not be deported. That case, stemming from the detention of a German named Kestutis Zadvydas, would eventually result in the release of an untold number of detainees from other countries, but it would not change the lives of the Mariel boat people.

The Zadvydas case was tried on narrow facts involving only foreigners who had been legally admitted to the country. A speech from a president about welcoming Cuban refugees notwithstanding, under a strict interpretation of immigration law the Mariels weren’t considered to have even technically entered the country.

If Benitez wins his case, it could be the best news the Mariels have received in a quarter-century.

His attorney, John Mills, said a favorable ruling would put more than a thousand Mariels on equal footing with other immigrants: “The immediate result would be that the government would not have the authority to detain them simply because they had an order of deportation.”

For many U.S. citizens, the Mariel boat people became synonymous with the title character in the Oliver Stone/Brian DePalma movie Scarface in which Al Pacino plays a murderous, coke-snorting Cuban refugee who takes over a drug cartel. Undoubtedly, some Mariels fit the Scarface profile. Many others do not.

In an interview at the Bastrop prison, Pablo Melvin Iglesias Garcia, a thin 40-year-old with a curly black ponytail, said he arrived in the U.S. at age 17. The decision to leave Cuba, he said, was an easy one for a young man his age. Cuban teen-agers loved American music, clothing, and culture. “I had this opportunity,’’ he said. “I never had the chance to speak to my parents.’’

The chance to make a life in America was a powerful lure. Castro’s Cuba, at best, was a dull regimen with few pleasures or amenities available, and, at worst, a dictatorship capable of imprisoning people for merely saying they wanted to leave the country. That, of course, could never happen in the United States, the Marielitos thought.

Histories of the Mariel boat people say only a few dozen refugees perished at sea. Some of those who made the trip say the toll was closer to several hundred. “At least I can tell you, from what I saw in the ocean, 300 to 500 people died on their way here,’’ Iglesias said.

For many, the dream began to dim shortly after their arrival. They had trouble finding families to sponsor them. They had trouble finding work, and the language barrier they encountered only fueled feelings of isolation and confusion. They had trouble just finding their way around. Cuba could be traversed easily in one day, while America seemed to go on endlessly.

The Cubans spread throughout the country, but many returned eventually to southern Florida where they had first come ashore. Iglesias, for instance, lived with a sponsor during his first year in the U.S., a Pennsylvania university professor who encouraged him to set out on his own path when he turned 18. Knowing no one else in Pennsylvania, Iglesias returned to Miami, and his life began its downward swirl.

“The people I knew there were living wild on the streets,’’ he said. Before long, Iglesias said he found himself in prison with a five-year sentence for unwittingly buying a stolen car. Released, he returned to his old ways and was re-sentenced to prison for buying stolen car parts. Having completed both sentences, he said, he’s been detained by immigration officials, with no new charges against him, since 2001.

As a Cuban lifer, he said he became all but nameless, his nationality an epithet. “Cuban’’ — he spits the word — “you can see the hatred in the way they say it. Barely do they call you by your name.’’

The Marielitos’ stories pile up like people on those boats in 1980. Marcelino Gonzales, now 55, made his way from the Florida Keys to New York looking for a job to help support his family back home. But when he turned to theft, he wound up in prison and then in immigration detention as a Mariel Cuban shunned by his homeland and his adopted country.

“It is true I fucked up,’’ Gonzales said in an interview at the Seagoville Federal Correctional Center outside Dallas, “but I don’t owe anything to society anymore. That’s the past. I’ve done my time. I’ve been in prison seven years for nothing.’’

Jorge Camdesuner Columbie fled Cuba when he was 26, “asked’’ to leave for refusing to serve in the military. He’s 50 now. In the United States, he lived in Arkansas and California, and went to jail for short stretches for marijuana possession and burglary of a car — but no violent crime. Picked up by immigration agents in March 2003 and sent to Seagoville, he’s now spent about as much time there as he did for the car burglary — but this time with no charges against him. Since then, his personal papers have been lost, his parents have died in Cuba, he’s lost track of friends and remaining relatives, and he’s not heard a word from his girlfriend, with whom he has a child.

“They don’t let you know nothing about what’s going on,’’ Camdesuner complained. “No matter how many letters you write, you don’t have an answer.’’ His complaint is a common one about the immigration bureaucracy, which has trouble returning reporters’ calls, much less responding to prisoners.

“You wait four or five or six months and you get the same letter as the year before, and the year before that,’’ Iglesias said. “They just deny, deny, deny, and that’s the way it goes.’’

Legal assistance, the Mariels said, is often hard to find.

“I haven’t seen any lawyers that busy themselves with our case,’’ said Alfredo Pomares. He said he served six months in a Cuban prison for stealing a radio. He said the first few years he was in the United States, he fathered three children, now all in their early 20s. He was arrested in 1996 for drug possession and hasn’t been free since.

“There is no difference between being locked up here or there. [But in Cuba] if I serve two years, I’ll be out. Here I don’t know.”

Segundo Burnes-Rojas said he has been to prison twice for drug possession. He was released in 1995 after spending eight years in prison on a cocaine charge. He was picked up a second time in 2000, again for drugs, and has been in immigration detention for the last year. Like others, he doesn’t understand why he remains locked up. And he also wonders why Cubans alone among the foreigners in immigration detention aren’t being released.

“It’s different with the others. The Vietnamese, [other Asians], they get released after 90 days, They process them,’’ he said. “We don’t know when we are going to be set free.’’

The Benitez case offers the best chance that Mariels have for ever being treated like other offenders. Some, like Pablo Melvin Iglesias Garcia, have all but given up hope.

“I get on my hands and knees and I pray every day. I say, “God, how can you not hear us?’ If I have to be here 10 years, I think I’ll take my life. Then I’ll be free — maybe in hell, but I’ll be free.’’

Julian Aguilar, a Dallas-based freelance writer, can be reached at julianaguilar@gmail.com.

Email this Article...

Email this Article...