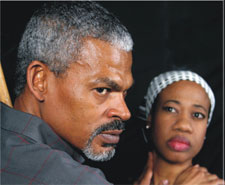

Lloyd W. L. Barnes and Regina Washington star in Jubilee’s latest production, an August Wilson piece. (Photo by Buddy Myers)

Lloyd W. L. Barnes and Regina Washington star in Jubilee’s latest production, an August Wilson piece. (Photo by Buddy Myers)

|

Fences

Thru Feb 20 at Jubilee Theatre, 506 Main St, FW

$12-20 817-338-4411 |

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Picketing

Jubilee swings for the ‘Fences’ but comes up short.

By JIMMY FOWLER

In a 2000 article entitled “Wilson’s Fences,” scholar and critic Joseph Wessling argues that playwright August Wilson’s first great critical and commercial success, Fences, is in fact a comedy — or, in the great surgical art of splitting academic hairs, a “metacomedy,” which means that it takes an omniscient view of humorous compassion over the family sorrow that unfolds.

Few theatre groups have been able to find the dark humor that Wessling saw in Wilson’s 1985 script. Countless revivals have staged the piece as one of the grim, almost funereal ceremonies that Wilson — one of the top two or three living American dramatists — is known for. “I’ll need to bring my box of tissues and some razor blades,” cracked one Jubilee Theatre insider about the troupe’s current production of that show: “August Wilson is sohhh depressing.”

Not in Rudy Eastman’s hands, however. The Jubilee director may be the first artist to put Wessling’s interpretation on the stage. To view Fences as a tragedy, in Eastman’s opinion, is to miss the wealth of cosmic comedy that the author has woven into his tight two-act work about an African-American family in 1957 struggling under the shadow of a cruelly cynical patriarch who is sliding slowly into alcoholism.

Wilson himself has taken a deliberately historical approach to his career as a playwright: He has so far written nine scripts in a projected 10-play cycle about the black experience in 20th-century America, one for each decade. Although there’s no shortage of suffering among his characters, it’s also true that the playwright regards the proceedings with a certain detached quality, as evidenced by the frequency of supporting roles that serve as oracles or, at the very least, as carriers of a larger spiritual and supernatural wisdom. In most Wilson plays, there is another level of awareness always operating inside the torrent of tears.

That possibility of transcendence through a sympathetic but mischievous higher authority has too often been lost in the stagings of his work, but not at Jubilee. Their Fences is playfully boisterous and full of a bravura that’s both disarming and overbearing. Perhaps it took an African-American theater company to kindle what has mostly lain dormant in this play. Backed by white producers and staged for overwhelmingly Anglo ticketbuyers, other productions of Wilson’s works may have been too literal-minded and dogged by white guilt. Jubilee Theatre seems determined not to dwell on the brutal heart that beats within this show, making all the intense onstage interactions seem fresher but frustratingly incomplete.

Troy Maxson (Lloyd W.L. Barnes, Jr.) is a fiercely proud 53-year-old garbage collector in an unnamed northern city who, as the play opens, believes he has made some peace with his life. An ex-convict and a chronic womanizer in his youth, he has managed to find a younger wife, Rose (Regina Washington), who adores him. His teen-age son Cory (Brian C. Duncan) excels in school and treats his stern father with affectionate respect. His brother Gabe (Laurence Pete) has been rendered a wandering Faulknerian man-child from a head wound he received in WWII, although the Maxsons have resisted institutionalizing him and keep him in their daily lives as a kind of cracked visionary who talks about running with hellhounds and lunching with St. Peter.

Troy, who loves to spin tall tales about his past in a loud voice, is haunted not so much by past sins as by former glory. He had a brief but celebrated career as a baseball player in the Negro Leagues. Once Jackie Robinson and others crashed the all-white world of professional baseball in 1947, the Negro Leagues became a historical footnote, and many of its talented players were left with their dreams of wealth and stardom unfulfilled. Ironically, Troy has grown to hate whites largely because of the decision to integrate baseball. His thunder, so to speak, was stolen by pioneers like Robinson. When a college recruiter expresses an interest in Cory’s skills as a high school football player, Troy all but brings the wood-frame house down around his family in booze-fueled fits of rage, jealousy, and infidelity.

Any production of Fences succeeds or fails on the central performance of Troy, a role that requires an actor to carefully negotiate his way through speeches full of prideful bluster and violent loathing without exhausting himself or the audience. Director Rudy Eastman appears to have found a solution by guiding Lloyd W.L. Barnes, Jr. to underscore the man’s impotency and petty egotism for laughs, albeit uncomfortable ones. The audience at a recent matinee responded with uproarious enthusiasm. Strutting and flapping his arms like a rooster on a perpetual barnyard tirade, Barnes evoked Red Foxx as Fred Sanford more than a few times. Trouble is, he repeatedly lets the angry buffoonery run away from him to the point of flubbing lines. Regina Washington gives as good as she gets as Rose, a woman who epitomizes the phrase “long-suffering” yet manages to react in surprising ways (and with zestful comic timing) to the consequences of Troy’s marital betrayal. There’s not much meat in the role of Troy’s aspiring football player son Cory, and Brian C. Duncan samples the scraps he’s handed too hesitantly to score much presence. As the mystical fool-cum-truthteller Gabe, Laurence Pete gamely attempts to humanize a character who is, at heart, a glaring theatrical contrivance. This Gabriel even comes with a trumpet slung on his back, waiting to perform on Judgment Day.

Jubilee’s Fences does yield surface pleasures under Eastman’s broad comic vision of the script, but they scatter away at the play’s conclusion, when Troy’s wife Rose must lecture her now embittered grown son Cory on the complicated nature of forgiveness and maturity. Simply put, the flailing, barking mini-monarch that was Troy in this staging lacks the complexity that would merit or even sustain the posthumous charity that Rose offers him. It’s an utterly hollow finale to a strangely antic Fences, suitably heralded by that paper-doll Gabriel tooting ineffectually through his yellow plastic horn.

Email this Article...

Email this Article...