Tom DeLay’s political action committee allegedly acted as a conduit through which corporate money was allowed to influence elections in states where direct corporate gifts are banned.

Tom DeLay’s political action committee allegedly acted as a conduit through which corporate money was allowed to influence elections in states where direct corporate gifts are banned.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

DeLay Leads Again

The Hammer’s fund-raising practices might have been copied by many in Congress.

By DAN MALONE

Even as Texan Tom DeLay, once considered the most powerful member of Congress, fights money laundering charges, a Washington-based nonprofit group is raising questions about other lawmakers who have engaged in fund-raising practices similar to those that landed DeLay in court.

DeLay, who relinquished his position as House majority leader after he was indicted by a Travis County grand jury, this week won dismissal of a conspiracy case against him but failed to persuade a judge to throw out a related money laundering charge. Both cases stem from fund-raising practices that DeLay — and, it appears, many others — used during the 2002 elections.

The allegations are based on a series of financial transactions in which political contributions from corporations flowed through so-called 527 congressional leadership committees — the number refers to a provision in federal tax law — and national political parties. From there, sometimes, the money went into political campaigns in states such as Texas where corporate contributions to candidates are banned.

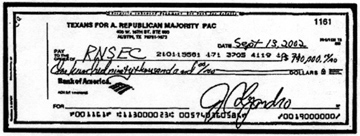

In DeLay’s case, the charges stem from the fund-raising activities of his political action committee, Texans for a Republican Majority. That committee, according to prosecutors, took in $155,000 in corporate donations, then issued a check for $190,000 to the Republican National State Elections Committee. Along with the check, which was graphically reproduced in the actual indictment against DeLay, came a list of seven candidates for state offices among whom prosecutors say the money was to be split.

Though DeLay is the only member of Congress to have been indicted for such transactions, a nonprofit research group based in Washington says dozens of other members of Congress, including four other Texans, appear to have engaged “in transactions similar to those that led to his [DeLay’s] prosecution.”

“At least 30 other members of Congress have accepted a total of $7.8 million in corporate donations to their leadership 527 committees since 2000,’’ the Center for Public Integrity said in a report issued two weeks ago. “These organizations transferred $3.5 million to national party committees, which later gave $14 million to candidates in state elections.”

The report noted that some of the heaviest corporate donors to the 527 groups were AT&T, with $716,000 in contributions; SBC Corp., which gave $698,000; and Philip Morris (now Altria), with $486,000.

Suzy Woodford, the director of Common Cause Texas, said corporate contributions have been illegal in Texas since the era of the robber barons. Corporate money was banned in 1905 with the passage of a law sponsored by a legislator named Alexander Terrell, who Woodford said “hoped to starve what he called the ‘corrupt machine politicians’ who gorged themselves on special interest money.’’

DeLay maintains he has done nothing illegal. He and his supporters have characterized the case against him as a political witch hunt. And they’ve said the practice that got DeLay indicted was common among both Republicans and Democrats.

The Center for Public Integrity’s report seems to back up the latter claim. Their list includes 13 Democrats and 18 Republicans.

Two current members of the Texas congressional delegation are on the list: Republicans Henry Bonilla of San Antonio and Pete Sessions of Dallas. The center said Bonilla’s committee made a $10,000 transfer and Sessions’ a $50,000 transfer, both to national parties. Two former members of Congress, Democrat Martin Frost of Dallas and former House Majority Leader Dick Armey, a Lewisville Republican, were also listed. The center said Frost’s committee transferred $85,000 and Armey’s $161,000 to national parties.

Frost, who is now a fellow at Harvard, did not dispute the center’s numbers but said his committee, the Lone Star Fund, gave no money to Texas candidates.

“I had a national 527, but it didn’t spend any money in Texas because it’s illegal to spend corporate money in Texas,’’ Frost said. “I have no idea what the national party did with the money the Lone Star Fund gave it,’’ but he said he assumes the party spent the money in states where it was legal to do so.

DeLay’s committee activities were different from his in another key way. “What DeLay is accused of is actually giving them a list of people they were supposed to give to in Texas,’’ Frost said.

Sessions said earlier this year that Travis County District Attorney Ronnie Earle’s investigation of DeLay appears “contrived simply to bring down Majority Leader DeLay.” Sessions’ chief of staff, Guy Harrison, said the center’s report fails to distinguish between 527 committees that made donations that eventually went to state candidates and those that did not. Session’s committee, according to the center, contributed $50,000 to the national Republican Party. But Harrison said Sessions’ committee “never incorporated in Texas and never gave funds to Texas state candidates.’’

Armey’s office did not respond to questions by deadline. Bonilla’s office did not return a phone call from Fort Worth Weekly. Nor did Dick DeGuerin, DeLay’s lead defense attorney.

The remaining money laundering charge against DeLay stems from the check sent from his political action committee to the national Republican Party. DeLay’s legal team contends that the allegations in the indictment, even if proven true, don’t constitute a crime. Texas, according to Susan Klein, a University of Texas law professor hired as a legal expert for the defense, didn’t include financial transactions by check in its laws against money laundering until 2005 — three years after the check from the political action committee was written.

“Conducting a transaction involving a personal check was not illegal in 2002,” she wrote in a legal analysis prepared for DeLay’s defense. “If it is not a crime under the Texas Penal Code to facilitate a transaction involving a personal check, then it cannot be a crime to conspire to conduct a transaction involving a personal check.’’ The judge in the case, however, let the money laundering charge stand.

DeLay, a Sugarland exterminator first elected to Congress in 1984, succeeded Armey as House majority leader in 2004. He has been admonished for ethical lapses three times by the House ethics committee.

His critics contend his indictment is merely the latest in a series of such ethical mistakes. DeLay, said Common Cause spokeswoman Mary Boyles, “is constantly pushing the ethical boundaries of Congress.’’

Email this Article...

Email this Article...