|

|

Brian Delay stops to talk to Curran on the SMU campus.

Brian Delay stops to talk to Curran on the SMU campus.

|

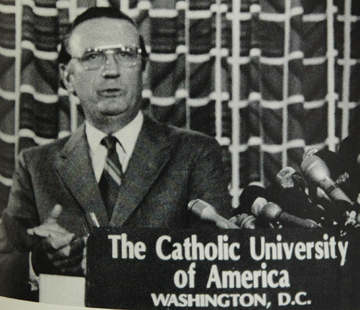

Curran received major news media coverage in 1986 when the Vatican stripped him of his license to teach theology in Catholic colleges.

Curran received major news media coverage in 1986 when the Vatican stripped him of his license to teach theology in Catholic colleges.

|

Curran talks to his secretary, Carol Swartz, in his bookstrewn office.

Curran talks to his secretary, Carol Swartz, in his bookstrewn office.

|

Curran has used his faculty position at SMU as a base from which to continue working for openness and equality in his church.

Curran has used his faculty position at SMU as a base from which to continue working for openness and equality in his church.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Loving Dissent

Father Charlie Curran has made a career out of standing up to the Vatican.

By JIMMY FOWLER

Charlie Curran doesn’t look like someone who’s doomed to be burned at the stake.

At 72, with worn sneakers and rolled-up sleeves, sitting in his book-lined office at Southern Methodist University, he looks like the low-key thinking man and professor that he is.

And yet, as a Catholic priest and brilliant religious scholar, his actions were apparently so heinous that an archbishop once accused him of “sowing scandal” among the faithful. What he taught was so scary that the Catholic Church’s modern-day successor to the Inquisition barred him permanently from teaching at Catholic colleges. Before the ban, he was so well-liked and respected that the entire theology faculty at his former university once went on strike to help save his job.

What did Father Curran believe and teach that caused such uproar? Well, in large part, the kinds of things you might suspect would get someone in trouble with the Vatican — that the church was wrong to strictly ban all abortions, all premarital sex, all homosexual relationships, all forms of birth control except crossing your legs for part of the month; that the church should allow women and gays to be priests; that priests should be allowed to marry. And that the church has screwed up royally in its handling of the pedophilia crisis, with repercussions that have been felt everywhere from Fort Worth to the farthest reach of church territory (which is to say, the whole world).

But Curran’s point of departure from Rome — and the reason that, 40 years after he first pissed off a pope, he is still a force to be reckoned with — goes deeper than arguments about sexuality in its various combinations of stripes and spots.

He believes in — and openly talks about — the fallibility of the church and its leaders. He thinks that Catholicism, like every other religion, ought to evolve along with society. He’s willing to point out when his particular emperor has no clothes, beneath that papal miter. He thinks laypeople ought not to be powerless within their own church. In short, he believes in freedom of thought and speech within his religion. And he finds alarming the growing tendency of the Catholic hierarchy — as well as fundamentalists in so many other sects and religions these days — to claim that their faith and theirs alone contains the single absolute spiritual truth.

You might say Curran has lost every battle he’s fought with those in the Catholic Church who would make its rules more rigid, its priesthood more controlled, its secrets more closely held. Nor do the official tides seem to be with him: The man whose investigation got Curran tossed out of his teaching position, the church official who’s been dubbed “God’s Rottweiler,” has been elevated to a post that some fear — and others hope — may move the Catholic Church even further toward conservatism and orthodoxy. The Rottweiler — former Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger — is the new pope.

None of which has changed Curran’s opinions or his steady, unflashy, long-haul campaign for what he sees as a more compassionate and egalitarian approach in the church’s teachings — even as he reaches an age when he’s becoming curious about who might continue the good fight in his absence. “There are days when one gets discouraged,” he said. “But I’ve never seriously contemplated leaving the church I love.”

And yet, Charlie Curran has not faded into the footnotes of Catholic history. Having established his reputation as the most outspoken dissident priest in the United States more than 40 years ago, he has continued ever since, through college courses, public lectures, and tv appearances, to work at triggering dialogue on those topics. During the past 12 months, he’s re-emerged with the most mainstream media cachet of his long career, as the reliable source for quotes from a liberal Catholic priest, one of the only outspoken liberal Catholic priests — or progressive Christians period — that the folks at CNN, the broadcast networks, NPR, and the Los Angeles Times seem able to locate. His autobiography, due out in March, is guaranteed to make Catholic leaders uncomfortable.

Beyond all those things, however, Curran’s most enduring legacy may lie in the kind of change that his opponents have always feared — among the vast numbers of seminary students and lay Catholics, where his version of how to live as a Christian in the real world bears far more similarity to their lives than the version espoused by Rome.

In Rochester, N.Y., in the early 1960s, Curran found himself counseling married couples in loveless or abusive relationships for whom divorce was simply not an option. The young priest had to explain to working-class couples why contraception was sinful and to insist to women that abortion was always wrong, even when an unexpected pregnancy meant disaster. Increasingly, he found it hard to reconcile those on-the-ground realities with the moral absolutes of his church.

Both the experiences of his flock and the need to raise questions on their behalf were familiar ground for Curran — he’d grown up in working-class Rochester, a city known as fertile ground for both ice hockey and progressive activists like Susan B. Anthony and Frederick Douglas. His parents — insurance salesman and homemaker — were devoutly Catholic by religion, and his father was a devout Democrat and speechwriter for local politicians, someone who encouraged his children to learn to write and speak publicly, get involved in public service and charity work — and to think for themselves.

Up to that point, Curran, who’d been ordained in his hometown in 1958, had been, in his words, “compliant” in church matters. He’d been educated in Catholic universities in Rochester and Rome, earning doctorates in moral theology and a license to teach in seminaries and Catholic colleges.

In 1965, the worldview of the hundreds of millions of Catholics underwent a tremendous upheaval when the findings of the ecumenical council known as Vatican II were released. The sweeping changes it wrought were both symbolic and pragmatic: The Vatican officially recognized that there were important spiritual truths contained in other world religions. Priests for the first time were allowed to say Mass in the native languages of the congregants rather than in Latin. The roles of laypeople in the church’s administrative and pastoral affairs were somewhat increased. Traditionalists fumed; liberals were heartened at what they interpreted as a loosening of authoritarian grip.

Curran saw Vatican II’s innovations as confirming his own increasingly progressive attitudes toward what he saw on the ground. The church wanted people to make decisions on marriage and birth control and other matters based on very specific moral precepts — but how moral was the church’s own behavior toward members who were struggling to integrate church teachings with the realities of their lives? And just how integral were those proscriptions to the core of the faith?

By that point, Curran had come to believe that the conservative idea that the church should resist influence from secular social developments was untenable, not to mention utterly at odds with 2,000 years of Catholic history. As he puts it: “I’ve always argued that the best Catholic traditions say that we consider doctrine an ongoing process, that Scripture alone isn’t enough, and that we must always review teachings in the light of present-day thought and circumstance.” He began writing and speaking about what he thought — and attracting attention for those views.

Carolyn Osiek, a nun and professor of New Testament studies at Texas Christian University’s Brite Divinity School, was a “junior person” in theological circles when Vatican II happened and Charlie Curran’s star began to rise. “He was very much a big name on the scene,” she remembered. “Those were heady times for a lot of people, because we saw Vatican II was opening the church up to modern culture. Change was on a lot of people’s minds.”

By the time Curran came to teach at Washington D.C.’s Catholic University of America in 1967, the formerly compliant priest from Rochester had an international reputation as a formidable moral theologian who wasn’t shy about challenging the church in his writings and lectures, especially in the areas of what came to be called “reproductive freedom.” When the board of directors threatened not to renew his contract shortly after he arrived, the entire theology faculty staged a successful strike in support of Curran’s reinstatement.

James Walter, currently a professor of bioethics at Loyola Marymount University, worked alongside Curran at Catholic University. He thinks he understands why his old friend’s assertive but non-confrontational style attracted support from peers, while his views were attracting frowns from higher up. “There’s never been any quality of the ‘ego trip’ about Charlie’s stands,” Walter said. “He’s a thoughtful man who respects the people who disagree with him. And, it must be emphasized, he is far from the only person to hold these beliefs. What Charlie did differently — and what so many people thought was arrogant — was to bring these subjects into the light of public discussion.” Curran was driven, Walter insists, by a desire to speak up for a laity that so often felt powerless within its own church.

“The key phrase to describe Charlie is ‘loyal dissent,’” Walter said — and indeed, that’s the title of Curran’s forthcoming book. “Many people have written about him as if he’s standing outside the church and criticizing it, which is wrong. He loves the church.”

Three years after Vatican II, the seeming liberalization hit a full stop, when the officials in Rome released a document called Humanae Vitae (often translated as On the Regulation of Human Birth). Before 1968, it had certainly been the teaching of the Catholic Church that artificial birth control and abortion were not allowed, but those beliefs had never been made official. With Humanae Vitae, they were solidified into dogma — verboten under all circumstances.

Curran, whose evolving beliefs were going in the other direction, reacted. He wrote and helped circulate a statement that read, in effect, that one could be a loyal Catholic and still disagree that artificial contraception and abortion were always, incontrovertibly wrong. He was the “ringleader” in getting about 600 Catholic experts in moral theology from around the world to sign it before the paper was submitted to the Vatican.

The protest had little if any effect on the official line about birth control, although it did serve to shine an even brighter spotlight on this American theologian, rabble-rouser, and general irritant to conservatives. Throughout the ’70s he didn’t shirk the glare, continuing to air his controversial opinions and arguments in his books and classes — endorsing the ordination of women as priests, saying that priests should be allowed to marry if they wished to do so, and acknowledging that monogamous homosexual partnerships could be considered “morally acceptable.” As always, he took pains to ground each of these proposed innovations as interpretations within the framework of long-held Catholic thought.

The Humanae Vitae protest, which had represented the apogee of Curran’s public role of loyal dissent, seemed at first not to have any effect on his standing with Rome. In reality, however, it had been the beginning of the end of his career in U.S. Catholic universities.

The Catholic Church, it has once been observed, is like an iceberg — it moves slowly but with great force. Curran, of course, hoped that his arguments might edge the edifice in a different direction. Instead, his career was nearly crushed.

The Vatican, which had been receiving complaints about Curran through the years, finally became concerned enough about the amount of publicity he was generating to take action against him. In 1979, the Roman office in charge of enforcing church doctrine opened an investigation into the particulars of Curran’s work as a moral theologian. The office was the Congregation of the Doctrine for the Faith; centuries ago, it had been called simply the Inquisition. The man in charge of it was Cardinal Ratzinger, who’d earned nicknames like “God’s Rottweiler,” “Uncle Ratz,” and “The Papal Enforcer.”

Seven years later, the Vatican ruled that Curran was “neither suitable nor eligible” to teach moral theology at seminaries and Catholic universities because his teachings were, according to one archbishop, “sowing scandal and giving confusion” among Catholics. The license in sacred theology he’d earned in Rome was yanked. Catholic University summarily refused to allow their star scholar to teach as a “moral theologian,” although he was tenured at the time. Curran sued in civil court to get reinstated, but a district judge eventually ruled that the university was within its rights to dismiss him.

A large group of conservatives within the priest’s own home diocese of Rochester paid for a newspaper ad that read, in part, “We call upon all Catholics to express their solidarity with the action taken by Pope John Paul II to restore doctrine and discipline in the Catholic Church. It has been an intolerable situation that Fr. Curran has been allowed to teach in the name of the Catholic Church while denying its doctrines.”

This time, Curran noted, there were no crowds of theologians and fellow clergy willing to strike in protest. The support he received among fellow priests and bishops was “mostly quiet.” The Vatican axe had fallen decisively, and few people wanted to stretch their necks out publicly for Curran’s career.

What did he feel at the time? His response is that of a deeply internalized man — not surprising, perhaps, given his lifetime of rigorous academic work. “Of course, I felt all those things — angry, sad, betrayed,” he said. “I sued, after all. But I’ve never been a brooder. I’ve always felt the future was the most important thing to focus on.”

The reaction doesn’t surprise Father Richard McBrien, an author, church historian, and theology professor at Notre Dame who has known Curran well for many years. “Charlie has always had the personality that picks himself up when he loses and puts himself back on the path,” he said. “Certainly he endured a lot. But he has always had a powerful ability to forgive his adversaries. Everyone knew [the rescinding of the license] was payback for Humanae Vitae. The Vatican has a long memory.”

Curran was not unemployed for long. He taught at Cornell, the University of Southern California, and Auburn before joining the SMU faculty as a tenured professor in 1991. Sometime before Curran managed to forgive those responsible for his firing, he invented a proverb for his students to remember: “I made up an academic maxim and told my students that it’s very old, but it’s not. It says: ‘A big heart does not excuse a stupid ass.’”

In any case, Curran still can’t be sure which stupid ass to blame. Years after the revocation of his license, Curran heard a third-hand “Roman rumor” — they’re a dime a dozen, he said — claiming Ratzinger had told someone that Curran’s case was the hardest he’d ever had to decide and that it had been taken out of his hands. The implication was that Pope John Paul II, whose kind and tolerant face belied a steely conservatism on sexual issues, had ordered the churchly hit. Given that John Paul II had reportedly once criticized Curran’s teachings as “lax and accommodating,” that’s entirely possible.

With the long, infamous list of Father Curran’s dissenting views, it’s probably best to state the things that he doesn’t believe. He is not, nor has he ever been, a sexual liberationist — the “I want to do what I want, whenever I want, to whomever I want” attitude is dangerous, he said. He does not endorse so-called abortion on demand (those procedures that stem more from convenience than necessity), nor the decision of anyone to engage in casual, multiple-partner sex. Nor has he ever claimed that the rights of any individual should be proclaimed above the needs of the church or society in general.

“Too often in popular discussion, issues get boiled down to ‘conscience vs. authority,’ or ‘David vs. Goliath,’ if you will,” Curran said. “Well, conscience can be just as wrong as authority. They must operate in tandem. If you’re going to make decisions out of conscience, it must be an informed conscience, one that has viewed the situation from all sides. The question must always be, ‘What is the objective moral truth?’”

Curran steadfastly maintains that he has never departed from the Catholic Church’s core teachings — those included in the creeds or revealed by the sacraments — in anything he’s written or said.

“Theologians such as Charles Curran challenge the Church’s positions on those teachings which are not defined as fundamental to its teachings,” Father Joseph Schumacher, pastor of Fort Worth’s St. Matthew Catholic Church, said an in e-mail, “since they are not found in the continuous traditions of the Church.”

Curran has never been as much the revolutionary as has been portrayed. It comes down to nuance. He respects the vows of celibacy required by most Catholic religious orders as an offering to God — he just doesn’t believe they should be mandatory, because, for much of church history, they weren’t. Nor does he believe such vows automatically make for a holier priest. As for the pedophilia crisis that has cost the church hundreds of millions of dollars in damage awards — and even more in diminished respect for priests and the church and a rising suspicion about its indifference to its parishioners — Curran, as usual, draws some perhaps-surprising distinctions. They have to do with the timeline of what he calls the church’s “hideous record of abuse.”

“I’m always wary of judging the past by the standards of the present,” he said. “The truth is, it wasn’t until the 1980s that society at large began paying widespread attention to the horrors of sexually abusing young people. So before that point, how could the church be different from everyone else? After that point, what happened was unforgivable.”

He also expresses some concern about arguably the most media-hyped church issue today — the presence and suitability of gay priests. “The criteria should be the same for homosexual as for heterosexual” in admission to the seminaries, Curran said. But with some reports estimating that more than a third of the U.S. male clergy may be gay (he doesn’t know if that’s accurate but thinks the percentage is considerably higher than in the larger society) he worries that the priesthood, as a profession, has become a default refuge for conflicted gay Catholics who’ve been taught they can’t form loving same-sex relationships and still be devout. He hopes for a wider, more diverse clergy. “I think the clergy should reflect the society that it ministers to,” he said. “We should have gay priests and straight priests and women priests and married priests with children.”

But such innovations, no matter how thoughtful, appear to be as unwelcome today as when Curran’s teaching status was pulled. Last year’s removal of Father Tom Reese from his position as editor at the Jesuit magazine America — authorized by Cardinal Ratzinger before he became Pope Benedict XVI — is troubling to Curran. Most observers agree that Reese was a political moderate in his approach to the publication’s content, yet he made the mistake of choosing to print criticisms as well as defenses of the church side by side in single articles, most of them written by practicing Catholics. Curran said he was disappointed that Reese’s fellow Jesuits didn’t take a public stand over what he calls “a misuse of authority,” but he understands why they hesitated. “Some of them also operate magazines all over the world, and they don’t want to be demoted. I think what happened to Tom can only be taken as a warning, and it is not a good thing for the church.”

Osiek, the TCU professor, said she suspects that some paranoia may be setting in as Catholic progressives keep waiting for the new pope to drop the other shoe, one that may never hit the floor. “I’d be careful about reading too much into Reese’s firing,” she said. “Things like that take a long time to happen, and they build up after a slow trickle of complaints to the curia. It’s not like people are hired to sit around the Vatican and flip through publications, looking for clergy to fire.”

The question of free speech within the church — what can be challenged and what is central to the faith — has always preoccupied Curran, so it will come as no surprise to learn that he is highly skeptical of the notion of “papal infallibility” — the 1891 Vatican ruling that a pope, under extremely restricted and official conditions, can single-handedly create what is essentially unchallengeable church law. In fact, there are only two universally accepted instances of infallible papal utterances, because there is much disagreement among experts and authorities over when, exactly, a pope is speaking infallibly.

Walter, Curran’s old colleague from his Catholic University days, agrees with such skepticism but is rather more blunt on the subject of “creeping infallibility” — the exploitation by papal officials of a general misperception by many Catholics that all or most of what is said by the pontiff is infallible. He cited a recent example from last year’s ugly imbroglio over Terry Schiavo and her vegetative state.

“Shortly before John Paul II died, his office released a statement affirming the church’s position on artificial hydration and nutrition,” Walter said. “Well, some conservative Catholics pounced on Terry Schiavo’s husband, saying, ‘The pope supports keeping Terry alive, his word is infallible, therefore the husband is a bad Catholic.’ What the papal office issued wasn’t any kind of official teaching; it was a press release. The pope never put on his tiara, sat in his throne, and declared infallibly that Schiavo’s feeding tube must be reinserted.”

Curran himself believes pontifical personalities can seriously affect the world-wide congregation. He said he has come to believe a centuries-old Roman maxim about the pope that he once found disrespectful: “ ‘An effective pope or bishop needs three characteristics: He shouldn’t be too holy, too healthy, nor too intelligent.’ The longer I’ve lived, the more I see that’s right. The person who’s not too much of all those things knows their limits, knows they are dependent on others, and is therefore not going to try and unilaterally run things.”

At 72, Curran continues to stump for more officially sanctioned debate within the church. Since being banished to the hinterlands of Protestantism, he’s not as much in the Catholic academic loop as he used to be. But he has not been timid about using the pulpit that SMU’s Perkins School of Theology has provided. Indeed, as a media figure tapped to give the “loyal opposition” view, this past year he’s been more in demand — and therefore more visible — than during the period surrounding his expulsion as a Catholic moral theology teacher. Last year, CNN, all three network evening news broadcasts, NPR, the BBC, the Los Angeles Times, and countless print media drew Curran into the media hurricane that surrounded the passing of John Paul II, the rise of Ratzinger, and the firing of Tom Reese.

Shortly after John Paul II’s death, Curran published his book-length critique, The Moral Theology of Pope John Paul II. Anyone who read it while looking for one of the many quickie, uncritical postmortem biographies released to accompany the avalanche of worshipful media coverage was likely scandalized, because while acknowledging the pope’s skills as a communicator and his concern for the poor, Curran also claimed that John Paul II’s triumphalist view of Catholicism as a force that eclipses other faiths had done “great harm to the life of the church.” Most importantly, he said, John Paul II’s visionary tendencies blinded him to the mounting pedophilia scandals that engulfed the church under his leadership.

As for the televised spectacle of the pope’s funeral, “The press coverage made it look like he was a monarch, an emperor,” Curran said. “The church is not a monarchy. But I guess it revealed one thing — that the papacy is over-centralized and over-authoritarian.”

Television news reporters relished the obvious question during the short-lived selection process in which Ratzinger became one of the top candidates: So, Father Curran, how do you feel about the prospect of the man who kicked you off Catholic campuses becoming pope? Curran admits with a chuckle that his prediction utterly missed the mark. He told interviewer after interviewer that the former enforcer of the doctrine would not be elected to the papacy — though he’d be instrumental in choosing who was — because, at 78, he was too old and his health was fragile. So much for priestly infallibility.

Just as he wasn’t able to predict that Ratzinger would head the church, Curran won’t try to guess whether Benedict XVI will usher in the strict, even iron-fisted regime that many progressive Catholics fear. Curran did pen an op-ed piece for the Los Angeles Times expressing disappointment over the new pope and reminding readers, lest they succumb to the temptations of “creeping infallibility,” that the church has had a history of slave-owning popes, among other instances of moral fallibilities.

He is adopting a wait-and-see attitude toward his old nemesis and even cites some reason for hope. There is a significant difference, he noted, between the duties demanded by the papacy and those of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, where Ratzinger earned his reputation as a hard-liner. Last year the new pope held a well-publicized dinner meeting with Hans Kung, the Swiss theologian who, like Curran, had his license to teach at Catholic universities stripped due to his contrarian views. (That decision was made by Ratzinger’s predecessor in the CDF). Curran saw it as a symbolic gesture of reconciliation between left and right tensions in Catholic intellectual circles.

McBrien, who admits Pope Benedict XVI “could lower the boom at any moment and prove me wrong,” also sees some positive signs that the new pontiff might not be the Teutonic taskmaster some fear. “He may not have treated Charlie very well,” McBrien said, “but he’s a very smart man. He’s self-effacing, and he doesn’t use the papacy as a showcase for his personality.”

Curran’s autobiography, Loyal Dissent, (Georgetown University Press) is expected to hit the bookshelves in May. He hopes it will provide a clear picture of his decades of faithful activism and, in the process, remind folks that although conservatives may be hogging the spotlight now, progressives continue to work for a softening of attitudes on social issues. Still, he declines to speculate on what kind of pragmatic effect, if any, his career of pushing for more liberal approaches to gender and sexuality issues may have had, except in the most professorial way. “I have lived my entire life in the world of ideas,” Curran said. “And I have always had faith that if people plant good ideas, they will sooner or later bear fruit.”

Curran and McBrien agree that there is no single heir apparent in current academic theology to replace Curran’s spirit of old-fashioned liberalism, and in Curran’s mind, that’s not a bad thing: He believes that, compared to the years when he was making his mark — and being marked in return — as a rebel, there is less of a reliance now on what any dissident moral theologian says because there is less obedience to what church leaders and intellectuals say about people’s private lives, despite what the conservatives want you to believe.

McBrien insists that his friend’s teachings on nuanced approaches to moral realities have so saturated U.S. seminaries that young priests and scholars de facto absorb them whether they can cite his name or one of his books. Others regard him as something of an underdog hero.

Osiek declined to comment specifically on any of Curran’s controversial stands. But she, too, believes the church is a living and changing institution. “Many in the church do not at this time believe they’ll be able to change or soften their views [on social issues] and still maintain the church’s institutional identity. But they can,” she said. “The church is like an amoeba. It simply adapts to new situations and realities and survives.” And as time passes, she said, the established church often accepts the wisdom of what were once incendiary ideas. “In church history, the dissenters have sometimes turned out to be prophets. But it often takes a generation or more to realize it.”

Curran’s ex-colleague Walter phrases it with typical candor: “If our identity as ‘good Christians’ depends on mandatory views about homosexuality and abortion, then we’re in deep trouble. That means we’ve lost the central, historical significance about who Christ was and what he did for us.”

The rigid conservatism that’s reflected on the political face of today’s mainstream Catholicism and Protestantism is related, Curran believes, to the overall “you’re either with us or against us” triumphalism that heavily influences many churches. Christians in the United States, he said, have always had a tendency to identify the country too easily and simplistically with God and God’s purposes, perhaps never more so than with the gradual rise of Protestant fundamentalists to political power that began under Ronald Reagan. “God is bigger than any one country, any one institution, any one cause,” Curran said. “In my opinion, a Christian’s primary allegiance should always be to their faith which is, in the end, borderless.”

But Curran insists progressives, including himself, are often unrealistic as well and get sidetracked by their own messianic drive. If conservatives mistakenly believe the church is “pure, holy, and without spot,” then crusading liberals often err in the notion that the church could be made that way if only the hierarchy would heed their requests. That’s why Curran never seriously considered renouncing his priestly vows or his faith. He long ago realized how silly it was, he said, to think that “if the Catholic Church isn’t perfect by 10 a.m. tomorrow morning, then to hell with it, I’m leaving.”

In the end, Curran believes many of his views that’ve been condemned as radical, even heretical, by the Vatican are already daily practice in many places. “If you define the church as ‘the members that form the body of Christ,’ then many of these [so-called “hot-button”] issues have been accepted,” he said. “Go to a parish in any mid-sized American city, and you’ll find Catholics who use birth control; divorced and remarried Catholics taking the sacraments; gay and lesbian couples who believe themselves to be good Christians participating in the life of the church.”

In his academic way, Curran has been preaching a vision like this for years. “In most institutions, including the Catholic Church, change always comes from the ground up,” he said. “It starts with the people.” Maybe, despite the protestations of conservatives and the establishment, it has already started.

Email this Article...

Email this Article...