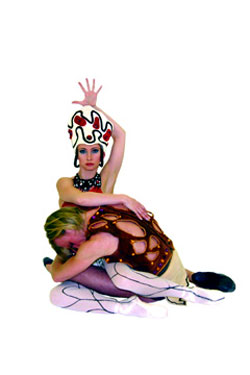

Olga Pavlova has Anatoly Emelianov under her spell, in ‘The Prodigal Son.’

Olga Pavlova has Anatoly Emelianov under her spell, in ‘The Prodigal Son.’

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Power Serge

MCB revives one of contemporary ballet’s most powerful pieces — along with a couple of oddities.

By LEONARD EUREKA

In Paris, just before and after World War I, a pudgy little man with pencil mustache and top hat named Serge Diaghilev single-handedly dragged classical ballet into the 20th century. He saw more potential in adventurous ballet than in ballerinas on pointe, dancing sugar-spun fairy tales, which were all the rage. An impresario with a knack for spotting talents and mixing them together in a creative brew, he guided some amazing collaborations for his innovative Ballets Russes company.

Diaghilev’s unfailing eye saw what dance could be, and he reached out to some of the most extraordinary people of the day, including young composers such as Stravinsky, Debussy, and Prokofiev; budding choreographers Fokine, Vaslav Nijinsky, and Balanchine; visual artists Picasso, Chagall, and Bakst; and dancers Anna Pavlova and Nijinsky. After the first performance of Nijinksy’s abstract setting of Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, in Paris, fistfights broke out between those who loved the production and those who were outraged. On the other hand, during Nijinsky’s curtain call after the premiere of The Afternoon of a Faun, some women in the audience were moved to rip off their jewels and throw them on stage.

The last of the Diaghilev ballets, The Prodigal Son, was choreographed by Balanchine and scored by Prokofiev, and it premiered a few weeks before the director’s death in 1929. A re-telling of the biblical parable, it remains one of the most powerful essays in dance. Balanchine re-staged the ballet for his fledgling New York City Ballet in 1950; in the title role was Edward Villella, the greatest American virtuoso of his day.

Metropolitan Classical Ballet co-artistic director Paul Mejia, a Balanchine disciple, revived the ballet in Bass Performance Hall last week, in a program that also included Paganini (Rachmaninoff and Lavrovsky) and Paquita (Minkus and Petipa), and his production easily ranks among the Arlington-based company’s best efforts.

The Prodigal was performed by another remarkable dancer, Anatoly Emelianov, who captured the restless innocence of the privileged son who thoughtlessly renounces family and fortune to go out and see the world, only to be robbed, stripped, and beaten. His tragic journey home, dragging his broken body, is a study in defeat and despair unequaled in dance. It’s nearly impossible to remain dry-eyed watching the young man fall on his knees at his father’s feet — forehead on the ground, trembling arms outstretched, begging forgiveness — and then be gently scooped up by his father and carried home.

Even though its plot is relatively straightforward, the ballet is complicated to stage. In particular, the dark-clad revelers whom the Prodigal encounters on his journey arrange themselves into bizarre, sometimes sinister configurations. One moment the dancers, joined at the back, scurry around on bent knees like demented crabs. The next, they’re lined up to form a giant, multi-legged caterpillar. One false move could spell disaster.

In the middle of everything is the Siren, a sort of Eve figure who seduces the Prodigal and hastens his fall. Olga Pavlova played the sultry, unfeeling creature here — a marvel of deviousness preying on her victim with total detachment. She reminded me of the late Margot Fonteyn, with her ability to melt into the character and become one with it.

Pavlova showed her technical virtuosity in Paquita, a tried-and-true 19th-century Russian showpiece of the kind Diaghilev sought to replace. She tossed off the bravura challenges with easy authority. During the first few turns of the obligatory 32 fouettes, she even daintily held the edge of her tutu between right thumb and forefinger. (As the going got tougher, however, she dropped the fabric to extend her arm and maintain balance the traditional way.)

Her partner was Andre Prikhodko, a young Russian who has quickly ascended to principal status in the company and seems always to be a sympathetic partner, with his own bag of tricks for virtuoso solos. He sometimes lands with a thud, but his leaps are high and his turns are as clean as you could want.

Six ballerinas each took a variation in Paquita — Katie Pruder stood out, but Kalen Hansen danced with great charm, and she and Pavlova were the only ballerinas who managed to dance quietly all evening. The unforgiving Bass Hall stage magnifies the clip-clop of carelessly worn toe shoes.

The evening opened with Paganini, an overwrought, Soviet-era psychological exploration of the life of the famous violinist accompanied by Rachmaninoff’s Rhapsody on a Theme of Paganini. The great Russian composer had collaborated with Fokine on a 1939 ballet produced at Covent Garden in London; Lavrovsky tossed out the material and created his own scenario and choreography for his 1962 Russian version. MCB produced the ballet six years ago with co-artistic director Alexander Vetrov as Paganini, a role he often danced back home at the Bolshoi Ballet in Moscow. Emelianov danced it here, and he flew through the manic jumps and turns with ease. But somehow, the angst and melodrama seem dated rather than vintage, swallowed up by pageantry and posturing — almost like an anti-Prodigal Son.

Email this Article...

Email this Article...