Exploitative or just plain cool?\r\nDon’t ask Austin.

Exploitative or just plain cool?\r\nDon’t ask Austin.

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

|

|

A D V E R T I S E M E N T

|

|

Vampires

On the screen, in the classroom, and on the stage, bloodsuckers are running roughshod.

By KULTUR

Even though After Sundown may seem like just another local straight-to-video fright about a bloodthirsty vampire from the Old West who returns to his biting ways in a small Texas town, Windblown Productions’ movie got some serious industry cred. The company that will distribute the DVD nationwide this summer is Lions Gate Films, a major Hollywood player and one that recently stuffed movie theaters everywhere with big-budget babies like Hotel Rwanda, Crash, and the less-schmaltzy and thus thoroughly more artful Larry the Cable Guy: Health Inspector.

Filmed last year in Fort Worth and Grandview, After Sundown was first picked up by bottom-feeders Barnholtz Entertainment, a Los Angeles-based distribution company that by dint of some black magic has Lions Gate’s ear. Bada-bing, bada-boom, Lions Gate bit on Sundown, pushing back the release almost a year but, y’know, they’re Lions Gate. What nickel-and-dime film outfit’s gonna argue with them?

Certainly not the dudes behind Sundown and Windblown, Christopher Abram, who wrote the script and co-directed with Arlington’s Michael W. Brown, and producer Keith Duncan. For Duncan, whose previous cinema work includes stints as a production manager and in art departments, Sundown represents an inaugural foray into the biz as a pure producer. The film is Abram’s second effort; his first, 2003’s The Fanglys, is a largely forgotten gorefest that looks every ounce the chintzy $2,500 job it is.

Don’t get the wrong idea: Abram and Duncan aren’t swimming in Lions Gate’s generosity and probably won’t be anytime this millennium. (The average B-movie typically doesn’t generate big money fast, and for all its winning attributes, After Sundown is decidedly average.) Yet what the two filmmakers have accomplished — a jin-u-wine deal with a Tinseltown giant — bodes well for both Windblown and the Fort Worth/Tarrant County scene in general.

“I am of the philosophy of abundance,” said Duncan. “It makes it easier for all of us [local filmmakers] if we can all make better pictures around here. That way, more distributors are going to pay attention ... even if the movie isn’t Lawrence of Arabia.”

Heck, After Sundown isn’t even Lawrence Welk’s 12 Days of Christmas. The main problem isn’t the plot, which is pretty engaging, but the jarring discrepancy between the reality of the low-rent special effects and the intense, obvious ambition behind them. Flicks with budgets in the neighborhood of Sundown’s $50,000 can get away with sparse settings, costumes, and make-up (i.e., Shane Carruth’s Primer, Jacob Aaron Estes’ Mean Creek, Napoleon Dynamite). But most of them aren’t period vampire movies like After Sundown. The fake blood, bottled water, and cowboy boots alone probably ran into the $20,000 range, leaving few excess greenbacks for cool stuff like fangs, six-shooters, and CGI technology.

So how did two blokes from Cowtown, Texas, and their undercooked yet enjoyable schlocker manage to sweet-talk Barnholtz and Lions Gate into lending a hand, er, paw?

Easy. They did a lot of research, found the best deal, and went after it. Their primary concern wasn’t money, Duncan said, but industry heft like the kind Lions Gate offers. What little cash the duo received went straight to the cast, crew, and investors. Usually, filmmakers take the money and run, but since Windblown looks like it’s on the verge of a big break, Abram and Duncan know to keep their machine running smoothly.

Abram and Duncan’s ambition isn’t just limited to special effects. Though the filmmakers want to pursue individual projects, Abram envisions a “movie factory,” an umbrella outfit that will allow the two upstart moguls to pool resources. “So if [Duncan is] doing a movie and I’m doing a movie, even though we’re separate companies, we’d approach [investors] as one entity,” Abram said. “You’re not bringing an investor in for just one movie. You’re bringing them in for several years.”

How the ‘West’ Wasn’t Won

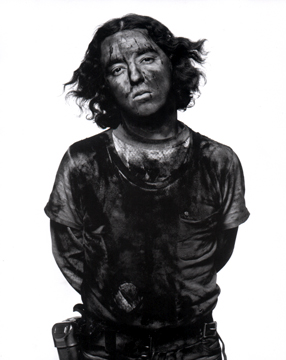

Austin has a lot of explanations for its self-proclaimed “weirdness,” including a photography exhibit that hung in Fort Worth’s Amon Carter Museum about 20 years ago.

In 1985, the museum commissioned work by acclaimed photographer Richard Avedon. His mission: to apply his probing aperture to the then-new American West, a mythical locale and one that hadn’t been interrogated (to use the academic term) since the days of naturalist painter Edward Everett. All he did was compose one of the modern era’s most memorable photographic symphonies, a massive and haunting collection of portraits of drifters, coal miners, and other victims of class warfare. In the American West, naturally, sent Texans and other Westerners into a tizzy. They accused the damned Yankee of exploiting our poor, huddled masses to further his career. But the naysayers, including our own Star-Telegram (that paragon of complex thought), failed to realize two important points: A.) The people in Avedon’s portraits weren’t figments of his imagination — they were real people, people the photog found, broke bread with, and didn’t have to sweet-talk into posing for him. And B.) a mechanical artist like Avedon can’t create from scratch interesting shapes, lines, and textures like a painter or sculptor; the photographer can merely discover and document them. Sure, he could’ve taken portraits of the moneyed philanthropists, neatly coiffed teachers, and other clean-living do-gooders that populate the region. But he would have added nothing to the dialogue about the West — most of us middle-classers see nice, clean people every day. Photographing “normal” Westerners (whatever that means) also would have pushed him into a different kind of corner: Westerners undoubtedly would have accused him of either ignoring the region’s poor out of respect for his patron or intentionally bringing out handsome subjects’ bad sides, ’cause if you’ve seen In the American West, you know: As effortlessly as Avedon furnished his pitiful subjects with nobility, majesty even, he could have turned our sweetest lil’ 90-year-old nun into the great Satan his-self. Kultur’s recommendation: If you’re ever blessed with the opportunity to stand in front of In the American West, just turn your brain off and look at the art the way you’re supposed to, with your eyes. No matter what you think of him or his photos, you won’t be able to walk away and not feel as if you’ve had a three-hour heart-to-heart with the veritable ground beneath your feet.

In Austin, in the wake of In the American West, some theater types got together and produced a show in an attempt to rebut the interloper’s artful reportage. In the West was not just a hit but, according to a recent issue of the Austin Chronicle, one of the first art experiences to help make the state capital (gag!) “weird.”

Just in time for the 20th anniversary of the exhibit, a revised version of the play, rechristened In2 the West, is now headed for the Austin stage and possibly, like its predecessor, to other nearby ports, including the Metroplex. The show opens this weekend at the Mainstage Theater of the Austin Community College, Rio Grande Campus, 1212 Rio Grande. For more info, call 512-223-3352.

Raging Frog

You gotta give props when props are due, even if they’re to a Horny Toad. So I gladly tip my beer-guzzler helmet to RTVF major and proud TCU student Chris Goble for recently thumbing his nose at the film industry, his profs, and sanity, corralling a bunch of friends, and filming what sounds like a respectable 45-minute feature.

Shot in Lubbock over spring break, his boxing drama Leading Fate is reportedly less about uppercuts and right crosses and more about dreamers who expend an entire oilfield’s worth of energy on trying to outlast or avoid utter failure. With Goble in the producer’s chair, writer/director and fellow Frog John Michael Powell worked the cameras, and a crew of 11 served as go-fers.

Goble doesn’t want anyone to confuse his bona fide work of cinematic art with some sort of student project or glorified term paper. TCU was a no-show in the help department, and Goble believes they couldn’t have cared less: Most of his classes, he said, stress industry analyses over gritty, hands-on filmwork like the kind he’s interested in. Worse, when faculty eventually learned of Goble’s project, they weren’t exactly enthusiastic. “They didn’t say anything to our face,” he recalled, “but I kind of got the impression.”

Before filming, Goble had lined up an investor, but the arrangement fell through, sticking the student with a majority of the project’s $2,500 price tag. Generating scratch forced him to clean out his savings account and hit up his grandparents for $500. (They gladly obliged.)

Working 20 hours a day, Goble, Powell, and crew amassed more than 10 hours of footage, and there are still four more scenes to go. Once editing is complete, Goble wants to enter the film in festivals to “get some recognition for what we’ve done.” He said he doesn’t care about recouping his expenses.

So not only did Goble put his young financial life on the line to complete Leading Fate, he missed spring friggin break — sacrilege to any college student, especially a Horned Frog — and he almost got worked over himself. For one scene, a real, professionally trained boxer had to step in against the lead character. The result wasn’t pretty — for the pro. “Our main character actually broke the boxer’s nose,” Goble said. “I had to rush him to the hospital that night. ... He looked like he wanted to hit something, probably me.”

Correction

Due to an editing error, last week’s column contains an incorrect statement. Local filmmaker James M. Johnston’s project Deadroom was submitted to and accepted by the SXSW Film Festival in 2005, not submitted and rejected in 2006. Fort Worth Weekly regrets the error.

Contact Kultur at kultur@fwweekly.com.

Email this Article...

Email this Article...